New book, A$29.99. NewSouth

Mike Lee, University of Adelaide, While a week can be a long time in politics, palaeontology typically moves more sedately, in keeping with its subject matter (the slow progression of the aeons).

But one area of fossil research is seeing remarkably rapid developments. Ever since the discovery of feathered dinosaurs in the late 1990s, the dinosaur-bird transition has been a research hotspot, with major new discoveries announced every few weeks.

Very recently, for instance, a new Russian dinosaur was found which supports the idea that all dinosaurs were feathered. Meanwhile a study of dinosaurian growth rates indicated that most were neither warm- nor cold-blooded, but something in between.

Fascination with feathered dinosaurs:

The scientific interest in this area has been matched by public attention. The evolutionary transformation involves two highly charismatic groups, dinosaurs and birds, each with great popular appeal.

The concepts involved are also exciting and readily comprehensible (such as evolution of feathers and wings in dinosaurs) and rather easier to convey than, for instance, the intricacies of the Higgs boson.

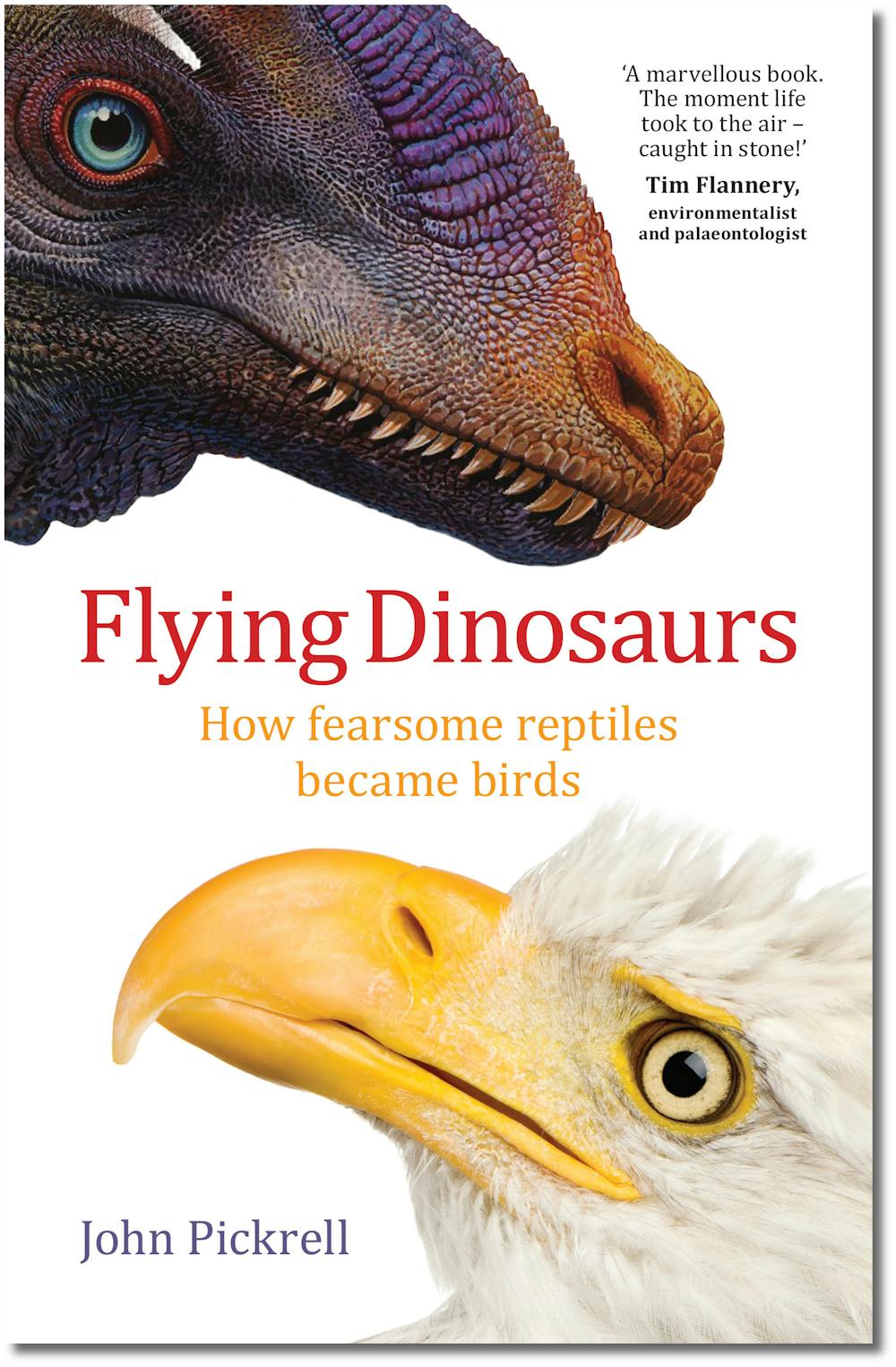

There has been a steady stream of books on this topic, the latest (for the moment) being John Pickrell‘s Flying Dinosaurs – How fearsome reptiles became birds.

The new book is a detailed and timely overview of our rapidly-improving scientific understanding of how massive, lumbering dinosaurs evolved into agile, flying birds.

There is deliberately succinct coverage of important historical events already detailed in earlier books, such as the wheeling-and-dealing behind the earliest Archaeopteryx specimens, and the wild-west “bone wars” between feuding palaeontologists Othniel C Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

The latest findings … for now

This frees up most of the book to focus on very recent discoveries not covered in earlier reviews. Many involve new technologies and new fossils; an impressively large proportion of the cited studies are from 2012 onwards (some even 2014).

The most recent fossils from China have suggested that the dinosaurian ancestors of birds probably sported long gliding feathers on both their arms and legs; birds subsequently retained only one set of wings.

Scientists have very recently discovered how to tell the colour of certain dinosaurs and early birds. While colours fade in fossils, the signature of “black” or “orange” (for instance) is retained in the structure of the grains of pigment in feathers. Thus, we now think that Microraptor and Archaeopteryx were mostly black, while Sinosauropteryx had a white and ginger-banded tail.

Hello black bird: Archaeopteryx, the first link found between dinosaurs and birds. Michael Lee, CC BY-SA

The new studies also close the gap between birds and dinosaurs, by finding more and more bird-like traits in dinosaurs. The first feathered dinosaurs from outside China revealed that at least some dinosaurs moulted like birds, replacing downy juvenile feathers with more structured adult feathers. CT-scanning has also revealed that many dinosaurs had enlarged brains with bird-like proportions of the various lobes. Even more intriguingly, these studies show that juvenile dinosaurs had particularly bird-like skulls, with delicate snouts and bulbous brains. Perhaps birds are perpetually juvenile dinosaurs – in the same way as humans retain many traits found in babies of chimps (our nearest relatives), such as skull proportions and propensity for play. All these discoveries, and other recent work, is engagingly covered in this book, along with related back-room dealings (regarding issues with fossil ownership, forgery and smuggling). Another dino book? But do we really need any more dinosaur books, including this? Though I’m undoubtedly biased, I think we do, as their relevance extends beyond ancient and (mostly) extinct reptiles.

The book features work by a new generation of palaeoartists attempting to capture dinosaurs in a range of behavioural activities such as this threat display of a nocturnal Epidexipteryx. Alvaro Rosalen

Dinosaurs are an ideal vehicle to convey important scientific concepts to diverse audiences (especially but not limited to the very young). They embody issues such as the immensity of geological time, the finality of extinction, and processes such as evolution, continental drift, and global climate and sea-level change.

Above all, they help convey an appreciation for the excitement of scientific discovery and logic of scientific enquiry, vital in today’s technological and (mis)information-rich world.

Flying Dinosaurs should have broad appeal. The interested layperson will find the topics very enlightening and the writing accessible. The pedantic scientist will also find new nuggets of information (the area is too broad and fluid for any single person to intercept all news). All readers will be hard-pressed to pick up any factual errors: Pickrell has a Masters in biology, and the book was proofread by an platoon of scientists.

The only problem with covering such a fast-moving field is the rapid obsolescence of any overview. Pat Shipman’s Taking Wing, a wonderful account of Archaeopteryx as the link between reptiles and birds, was outdated virtually instantly. Unfortunately it appeared in the late 1990s, immediately before the plethora of feathered dinosaurs revolutionised the field. Like any book on a vibrant field, Pickrell’s book will probably require an update sooner rather than later, but he will probably be thankful that this is the case.

John Pickrell will be talking more about how dinosaurs became birds in a free lecture on Thursday September 4 2014, 5.50pm-7pm (registration requested) at the University of Queensland’s St Lucia campus in Brisbane, as part of his involvement in this year’s Brisbane Writers Festival.

Mike Lee, Senior Research Scientist (joint appointment with South Australian Museum), University of Adelaide This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|

Flying Dinosaurs – How fearsome reptiles became birds

City Lights

by V Shoba, Has culture lost its place in Bangalore? Askew: A Short Biography of Bangalore | TJS George | Aleph | 116 Pages | Rs 299

FOR MANY LONGTIME Bangaloreans, the reality of today comes up short against the reverie of yesterday. A many-headed beast feeling its way forward without quite knowing how, the city, in a former life, had been an isle of bliss. In Askew, TJS George, a senior journalist and a Bangalorean, turns flaneur of that cosy past. He nostalgises the ‘Bangalore way of life’ before progress turned its ‘grace to gluttony’. ‘The problem was that IT transformed Bangalore in ways earlier bouts of industrialization and immigration had not. The old agreeable Bangalore was now replaced by an aggressive Bangalore where no one had time for his neighbours,’ he writes. But what makes this slim volume a keeper is his reportage: from the crowded platforms of Bangalore’s railway stations during the unfortunate exodus of the Northeasterners in 2012, from inside the burgeoning community of IT professionals who have moved from America to India’s Silicon Valley expecting potholes and walking into pitfalls, from the establishments that define Bangalorean food.

The author finds, in the incessant movement of the city—a garden city made over, first by its public sector units, its mafia and its liquor industry, he tells us, and then by the IT companies— characters that stand out in the human sprawl. Some of them are familiar: Kempe Gowda, the 16th-century founder of Bangalore whose mother told him to ‘build lakes, plant trees’; ‘the quiet Vittal Mallya’s unquiet son Vijay Mallya’; N Lakshman Rau, a much-admired administrator who laid out Jayanagar, one of the largest planned neighbourhoods in Asia, in 1948. We also meet more obscure people from the pages of Bangalore’s history: Bhairavi Kempegowda, a gifted singer who would enthrall his guru’s neighbours in Basavanagudi with his unimpeachable rendition of Bhairavi when not drunk; V Harish, a barber who collected Kannada literature and recreated the hairstyles of Kuvempu, Shivarama Karanth and other illustrious men of letters; MP Jayaraj, a former Congress youth wing head-turned- Bangalore’s first gangster boss and other unsavoury elements whose gang wars shaped modern Bangalore.

In a chapter on the food that sustained a generation of the city’s scholars and artists, we run into R Prabhakar, the ‘Dronacharya’ of Bangalore’s restaurateurs and the man behind the 5,000 Darshinis dotting the city today. Pioneered in 1983, a ‘darshini’—that which is visible—is a pocket-friendly restaurant modelled after Western fastfood joints, with an open kitchen. Instead of seating, it has high round tables at which people stand and slurp down their vada-sambaar. The author takes us right into the May 2015 wedding of Prabhakar’s son, marked by ‘the meal of a lifetime’ served up by the state’s top restaurateurs who had volunteered to take charge of the kitchen.

In the author’s telling of Bangalore’s cultural history, its successful families are major landmarks: the Narayana Murthys, the Adigas, the Maiyas and the Koshys. Many of the city’s triumphs are attributed, and rightly so, to these enterprising families, but there is precious little about the common man and his mundane life. The immigrants, among them start-up entrepreneurs who have changed lives and made fortunes, also fall by the wayside of this ‘biography’ of Bangalore.

Nandan Nilekani, civic activists and other political aspirants make cameo appearances, part of an ensemble cast chasing a parallel plot for a better Bangalore. Anything, one would think, is an improvement over a city of frothing lakes, unnecessary flyovers built so that government officials could siphon off money, and garbage transport controlled by the mafia. But can Bangalore’s ship be righted? The author raises another question: in this laboratory of social and economic change, has culture lost its place? Is progress no longer co-terminous with civilisation? And he goes on to answer: ‘Bangalore held on its soul force. How many cities would see writers and students holding a wake as Bangaloreans did for the Premier Book Shop when it closed in 2011?’Source: OPEN Magazine

|

The Beautiful Blood Ceremony

by Shylashri Shankar: Shylashri Shankar is a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, What the best of Japanese noir says about democracy, authenticity and the nation. HERE IS HOW you write a brilliant Japanese crime fiction novel. First, revive the sense of wonder, of the fantastic, in the crime by introducing a very attractive mystery. Create an element of surprise—a single mother murders her abusive ex-husband and a neighbour knocks on the door and offers to create a perfect alibi (Keigo Higashino’s The Devotion of Suspect X), or co-workers in a factory that assembles lunch boxes design a macabre way of getting rid of the body by chopping and packaging and distributing it in different parts of Tokyo (Natsuo Kirino’s Out). Then include the puzzle element of who did it (or if you already know that at the beginning, then show how that person evades the police). It is important to use science and rationality in this element; the solution to the mystery must be logical. Then layer it with the social, political or institutional tussles roiling Japanese society (the underling cannot contradict the boss even if the latter is wrong, about 1 million youth—mainly men—suffer from ‘hikikomori’, which means being confined, where they lock themselves in their bedrooms because they do not measure up to social norms). Create, in EM Forster’s words, ‘round’ and realistic characters. As Keigo Higashino points out in one of his interviews, “Rather than explain the significance of everything at the end of the book, I wanted to describe the characters’ actions and intentions at the beginning so I could better portray their feelings of guilt and anguish… Japanese people like it this way.” Even better if you bring in sadomasochistic elements. Also, if you can, tweak and play with past classics from other parts of the world.

Most of these elements infuse Keigo Higashino’s The Midsummer Equation. On one level, it is reminiscent of an English country house mystery, except that it is set in an inn on a once-prosperous summer resort. There is a cool and highly Western undercurrent running through the book’s plot and is evident in the technique deployed by the protagonist, a brilliant scientist and university professor, Manabu Yukawa aka Dr Galileo to his friends in the police. Yukawa arrives in Hari Cove on a train and his compartment companion, Kyohei, is the teenaged nephew of the owner of the Green Rock Inn. Kyohei is our guide in the novel. Yukawa decides to stay at the inn while attending a conference where he is supposed to speak about an underwater mining operation that wants to drill for a valuable ore found in rock off the seabed. The Cove’s denizens are divided on the issue. The environmentalists are led by Narumi, Kyohei’s older cousin sister, who is worried about the drill’s impact on the sea life and coral reefs, while their opponents who have seen the once-busy tourist spot dwindle into a backwater, pin their hopes on the development project. Though invited by the mining company as an expert, Yukawa is even-handed about the issue; he upbraids a company executive about not being honest, and also tells Narumi that she has to respect the other side’s work in order to find a true compromise. After a heated panel discussion, Galileo returns to the hotel and finds the Narumi’s parents frantic about the disappearance of the only other guest. He is found on the shore at the foot of a cliff by the hotel.

An accident, think the local police. But when the cause of death is carbon monoxide, and the victim turns out to be a former Tokyo homicide detective who could have been investigating an old crime, Tokyo gets involved. The police ask ‘Dr. Galileo’ for assistance. Yukawa’s investigation connects an ancient crime (a sometime Hari Cove resident was convicted of killing a Tokyo hostess) with the Green Inn family while traversing a labyrinth of love, guilt, shame, selfless acts and happiness. Alibis worthy of Agatha Christie, and split second timing reminiscent of Dorothy Sayers confound the detectives. But not our Galileo, who has been teaching the nephew scientific principles (firing water bottles into the ocean) for a school project. Yukawa’s avuncular sternness with Kyohei, and his concern for Narumi are especially charming since they reveal a kind awareness of human frailty. It would be fair to say that science reveals the murderer and the modus operandi, while the selfless (and almost suicidal) act of an important character bestows spiritual depth to the story.

The five books in Keigo Higashino’s Galileo series have sold more than 3.2 million copies in Japan. Another prolific writer of travel mysteries, Kyotaro Nishimura, had a taxable income of 393.5 million yen in 2003. Six Four by Hideo Yokoyama sold a million copies in Japan in six days! It is surprising that the Japanese, whom many foreigners view in clichéd terms as homogeneous, patriarchal, orderly, with low crime (except the triads who have their own spheres of activity that rarely impinge on a common citizen), are such dedicated readers of crime fiction. After all, unlike China, the Japanese do not have an indigenous tradition of crime and detection stories. It was only in late 19th century, as Japan borrowed ideas from the West, that the detective genre was first translated into the serialised novels in magazines. It is also surprising that a blend of science with a logical deductive method and a fantastical element characterises present day Japanese detective fiction. The starring role in the wonderfully atmospheric A Different Equation is played by scientific thinking, though leavened by an awareness of human frailty.

At another level, Higoshino’s books are a blend of science, social concerns and Honkaku, a concept proposed by Saburo Koga in 1925. Honkaku is a detective story that mainly focuses on the process of a criminal investigation and values the entertainment derived from pure logical reasoning. In writing this way, Higoshino is returning to the theme that has infused state and citizen building in Japan in the 20th century—a close link between science, crime fiction and Japanese nationalism. Science and rational thinking were harnessed to nationalism by the imperial state to create a perfect imperial subject, and in the post-World War II democracy, a perfect Japanese citizen. Edogawa Rampo (a pen name which, if one pronounces fast in Japanese style sounds like ‘Edgar Allen Poe’ in whose honour it was assumed), a popular writer of fantastical detective stories in the 1920s and 30s decreed that the real scientific spirit was found in this genre. As Hiromi Mizuno points out in Science for the Empire: Scientific Nationalism in Modern Japan, promoting science was intimately connected with wartime patriotism and was often described as ‘scientific patriotism’ (kagaku hokoku), which literally means ‘serving the nation through science.’ The ideal of Japanese womanhood was symbolised in articles like Science of the Kitchen: The Conversation between the Housewife and her Maid, which emphasised the rationalisation of home management. By the early 1940s, the Ministry of Education mobilised the concept of scientific patriotism to educate the ideal Japanese citizen through sweeping reforms in the school system wherein science was given a significant role from the first grade onwards. The ideal imperial subject, as Mizuno points out, would be rational, creative and technologically skilful so that he or she could contribute to national defence and the rise of national power.

Post-war Japan continued to promote science; ‘scientific nationalism’, a term coined by Mizuno, survived in the post War era as a legitimate form of nationalism (especially when other forms were discredited post-War), and this was replicated in crime fiction. At the same time, in line with the advent of democracy in post-War Japan, social issues came to the fore, and were tackled by detective novels such as Seicho Matsumoto’s Inspector Imanishi Investigates. Detective fiction came to have a close relationship with Japanese high literature, unlike in the West where detective fiction is dismissed as belonging to popular genre fiction and often relegated to the pulp fiction category—something that can be read once but not repeatedly like true literature. The term for a detective novel is ‘suiri shosetsu’ (novel of reasoning).

IN THE 1980S, a group of young writers published ‘authentic’ detective fiction. This group (who include Kirino and Higashino) revived the classic puzzle-type stories—so there was authenticity of form too, rather than simply of content. For instance, in an interview, Kirino said that the here and now of Japan is fraught with problems, especially between Japanese men and women, caused by the inability of most men to grasp that women want more than the usual ‘3-piece set’ of marriage, home and children. Not surprising then that Japan was no 101 (out of 145 nations) in the 2015 global gender equality rankings.

Six Four, the current publishing sensation from Japan, epitomises the sublime ‘high literature’ level that a Japanese police procedural can ascend to. Don’t be put off by the size. It is an easy read. At first I thought the numbers were the Japanese equivalent of ten four—‘message received.’ But it is the 64th year of the Showa emperor—the date on which a seven-year-old girl, Shoko, who had been kidnapped, and whose father, a pickle manufacturer had paid the ransom, was found dead in the boot of a car. The statute of limitations on Shoko’s murder is about to expire. The detective, Yoshinobu Mikami, who had been on the police team that had tracked the father during the ransom payment is now (20 years later) press director of the regional police, handling a set of disgruntled crime reporters. Mikami had initially tried to reform the relationship by being more honest with reporters, but when his own daughter, Ayumi, runs away, his world falls apart. His boss uses the disappearance to keep Mikami in his debt, and refrain from such independence. Each time there is an unidentified body of a young woman, Mikami and his wife get to view it for obvious reasons. At the start of the book, Mikami is informed by his superior that the police commissioner wants to launch a last-ditch attempt to find Shoko’s killer and also regain ‘face’ for the police. It is up to Mikami to get the father’s acquiescence and bring the press on board. A very difficult task, he finds, since the Press is extremely angry about the heavy-handed way the police (and the laws) filter information, and keep juicy details (in this instance a hit-and- run case) under a cloak of anonymity. Mikami revisits the Six Four case file and finds some unexplained matters including a glaring mistake by the police. There is a mysterious ‘Kobe memo’ that some within the police are anxious to suppress, and there is the matter of silent phone calls to Mikami’s residence, that may or may not be connected to Shoko and Ayumi. There is tension between Tokyo and the regional police, and the commissioner’s arrival may include a momentous announcement that could spell doom for one of the divisions. Mikami is stuck in a situation where he is viewed with suspicion by those in the media division because of his former assignment as a detective, while his former division members ask him if he has switched sides and become a lapdog of the media director. He has to navigate these difficulties, while trying to keep his job so that the police force will continue to search for his missing daughter. His wife remains glued to the telephone in case the daughter calls ‘again’. Another kidnapping occurs, and surprisingly follows the same trajectory as the Six Four case. The denouement is explosive, unexpected, yet highly satisfying. All these elements hook the reader.

Six Four’s appeal comes from the taut rendering of dilemmas that have universal resonance. We plunge into Mikami’s life conundrums such as the tussle between being a father, and being a loyal member of the police force; between loyalty to his old job and life and his new position. And we see him carve, without melodrama, a third way out of an either-or dilemma. The tone is detached, yet, as the novel progresses, we too savour Mikami’s realisations about what really matters to him and what is worth fighting for and going out on a limb. For instance, he realises that tactics can never genuinely move a person; that one had to tell the truth and trust the other person to keep it secret.

Six Four is a tour de force of a Japanese police procedural because of the deft, yet measured story-telling style, and the way in which the author handles the mysteries, the personal grief and the Machiavellian games of those who inhabit large organisations. In most police procedurals, the author would sketch a skeletal view of inter-departmental feuds, and the clashes between the detective and his or her superiors whose goals may require some moral slippages on the detective’s part. But in Six Four, we inhabit an intricately shaded drawing where each stroke of the pen captures yet another layer of questions confronting Japanese society and state institutions. Mikami had ‘hoped that they were both torn between their allegiances, single bodies with two minds, existing in a world where hierarchy was everything… but he’d been wrong.’ ‘The police force is monolithic,’ decrees Mikami’s rival (and now a senior officer) from his youthful days in a martial arts academy. Am I a father first or a member of a revered organisation? Is losing face worse than telling the truth? What happens to those who do not or are not allowed to reveal the truth? These questions are seamlessly woven in with present day woes of Japanese society. At the same time, foreign readers can connect to these dilemmas. Who has not witnessed or experienced the machinations of one’s colleagues, subordinates and bosses or confronted some of the questions faced by Mikami?

In Japanese textbooks of the 1930s, the emphasis was on making Japanese children think, observe (nature) and act rather than mechanically memorise information. Such thinking for oneself was a double-edged sword—a fact recognised by some ministry officials who said that students might start questioning Japanese history. At that time, the disconnect was resolved by linking science and ethics with the notion of a good imperial national subject. But today, in democratic Japan, it is more difficult to subdue dissent. That is precisely what ‘authentic’ crime fiction in Japan reflects—the questions asked by those who occupy unequal positions in a democratic nation. Source: OPEN Magazine

|

Burning Bright

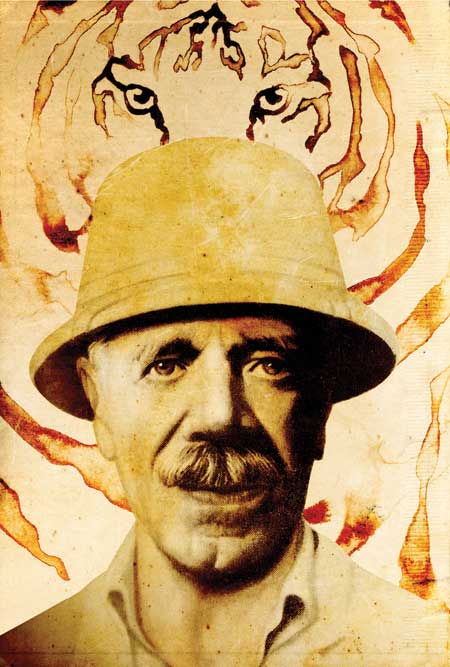

Stephen Alter reimagines the enigma of Jim Corbett : In the Jungles of the Night: A Novel About Jim Corbett | Stephen Alter | Aleph | 193 Pages | Rs 499

by Janaki Lenin (Janaki Lenin writes on wildlife conservation. Her latest book is My Husband and Other Animals,) AN AUTHOR fascinated by man-eater slayer Jim Corbett has a tough task. At least four biographies of the famed hunter of man-eaters and bestselling author exist. His fans have written blog posts, articles and books on him, even pinpointed locations mentioned in his books. So how can a writer approach the subject with a fresh perspective?

Faced with the quandary, Stephen Alter switched genres: he fictionalised his subject. The result is In the Jungles of the Night: a novel about Jim Corbett, the title excerpted from William Blake’s The Tyger.

Alter writes fiction and non-fiction books with equal deftness. Based on what Jim reveals of himself in his books and DC Kala’s biography Jim Corbett of Kumaon, Alter’s novel has three sections, portraying a 13-year-old Jim, a seasoned hunter, and an elderly émigré.

The teenage Jim in Alter’s imagination is a fern collector, a solitary pursuit, much like hunting big cats. On the quest for a rare species, the boy discovers the desecrated coffin of a young woman. Ten years earlier, the 19-year-old lady had been killed and the police and community believe the culprit to be a man-eating leopard. Soon afterwards, Jim’s elder brother, Tom, kills a leopard thought to be the assailant. But now, after the sacrilege is uncovered, Tom hints to his brother that there may be more than meets the eye.

An intrigued Jim investigates the spot where her body was found. Even at that age, he reads tracks like he would later as a hunter. His keen observations aid the police in uncovering what happened to the woman.

Alter, born in India of American parents, shows how cruel English society was to its India-born compatriots. Murch, a dissolute Englishman fallen on bad times, is a third-generation White like Jim. Even before Murch’s fall from grace, his peers call him names and shun him. The reader can’t help wonder if Jim’s family faced similar discrimination. Alter offers ‘country-bottled’ Englishmen as a parallel for untouchables in Indian society. Yet, no matter how lowly some Whites were regarded, they always ranked higher than Indians.

Alter has Jim, a renowned hunter by now, go after the ‘Man-eater of Mayaghat’ in the next chapter. Set in 1926, this is the same year Jim shot the leopard of Rudraprayag, said to have killed more than 125 people and a tigress that stalked the labour camps of Sarda valley.

This 90-page-long chapter of the hunt for the man-eater is classic Corbett, although it’s written in the third person. Vivid natural history observations relieve tense sections as Jim stalks the cat through the jungle. The behaviour of terrorised labourers is reminiscent of people in today’s Sunderbans, where they routinely fall prey to tigers. After the tigress claims two more humans, Jim shoots her dead.

A couple of unusual elements set this tale apart. The lack of love interest in Corbett’s life has mystified readers. The only woman in his life was his elder sister Maggie. DC Kala, in his pop psychoanalysis, suggests an eight-year-old Jim may have been scarred while chaperoning his grown sisters as they bathed in the river. Did he love a woman? Was it unrequited love? Or did he not meet a soul mate at all? No biographer sheds light on this aspect of his life. Unfettered by real life, Alter’s Jim gets laid.

Kaiyu, Jim’s fictional woman friend, is no wallflower. She’s a toughie, living alone in the forest with no male protection. She knows the way of the wild and ventures out when others live in terror of the man-eater. This gains her the respect and concern of the 51-year-old bachelor. But when she makes the first amorous move, Jim follows.

A factor that sets Jim apart from other writers of shikar books of that time was his empathy for Indians, often those of marginalised classes. In his travels and conversations with local people, he would have known that the forest laws deprived them of their livelihoods. The extensive network of railways needed vast stands of timber trees like sal for sleepers. To safeguard these resources, the department forbade others from hunting and grazing in its forests, a traditional monopoly the institution continues to exercise today. This undercurrent of tension is missing from Jim’s books.

Alter turns up Jim’s social consciousness a notch or two, forcing him to acknowledge the travails of Banrajis, a tiny indigenous community of hunter- gatherers. The department’s deforestation is far more damaging than the small- scale hunting of indigenous people. But he doesn’t change Jim’s personality too much. Jim still sees the British administration as paternalistic and views the activities of Bimal Swadeshi, the local Congress activist, with distaste. To be fair, he has no tolerance for the bigoted Andrew Kincaid, the District Forest Officer.

Alter shows Jim isn’t the infallible hunter or the crack shot he’s thought to be. While waiting for the tigress to make an appearance, he mistakenly shoots at a leopard that scavenges a human kill even though he can’t see in the dull light of gathering nightfall. Worse, his bullet misses its target. “Too often we think of Corbett as someone who never failed and never made a mistake,” says Alter. “In his books he describes several incidents in which he missed his target or misinterpreted signals in the jungle. I suppose the episode with the leopard is meant to suggest the uncertainties of being in the dark.”

DESPITE HOW MUCH of his work occurs at night, Jim doesn’t carry a light. Not only is he in danger of becoming the man-eater’s next meal, it’s also the time when snakes bite people. If there’s one creature that he cannot stand, it’s the snake. Not only does he try to kill every single one he sees, he believes slaying one brings him luck in hunting man-eaters.

Jim entertains a host of other supernatural beliefs. In the manner of people of that time and place, Kaiyu too has her own understanding of the forest and animals. She warns that a goddess protects the man-eater, and he should placate her by offering something of himself. She speaks with such authority about the tigress’ habits, the reader and Jim wonder if she’s the goddess. The climax of the chapter is not the moment when the man-eater falls dead. After he returns to the camp, the labourers arrive with the lifeless body of Kaiyu. A panicky Kincaid had shot her when labourers demanded better pay.

Is this the ‘offering’ that appeases the goddess and the reason Jim’s bullet finds its mark?

“Perhaps,” replies Alter. “I wanted to suggest that the way [Kaiyu] understands the forest is through a sense of submitting to nature’s realities as well as its mysteries. Corbett too seems to have had this kind of empathy for nature in which he allows himself to become absorbed in the tigress’ presence, even as he tries to kill her. He certainly recognises that there may be a mystical link between Kaiyu and the tigress, even if it is nothing beyond a myth or metaphor.”

Jim could have also be offering something of himself when he submits to Kaiyu’s sexual overtures.

The last chapter’s title ‘Until the Day Break’ is taken from the epitaph on Jim’s tombstone. Alter changes voice here, going from third person to first person as if the 78-year-old Jim wrote it in Kenya.

The elderly Jim assesses his life, experiences and decisions. The chapter covers a lot of ground in a manner not unlike the elderly are known to do. Did he have to leave India? Alter foreshadows his distrust of Indians’ aspiration for self-determination in the same way Jim relates to Bimal Swadeshi. So his decision to emigrate to Kenya appears logical.

Although he enjoys the extravagant wildlife spectacle for which Kenya is renowned, Jim writes little of its people. Nor does he describe the sights and smells of the savannah as he did so wonderfully the Himalayan jungles. In Alter’s imagination, he did express at least a tinge of regret for leaving the land and people he loved.

Here too, unexplainable events occur. A goat he tethers goes missing and he finds it later in the village. Who could have set it free? Jim also swears he filmed a leopard but when the developed film returns, there’s no sign of the cat in the film. Was he hallucinating?

“I decided to tell this part of the book in his voice, a rambling raconteur who plays with the facts even as he tells the truth,” says Alter.

This triptych novel presents the enigma of Jim Corbett to another generation of readers. Read it. You won’t regret it.Source: OPEN Magazine

|

Review: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

Stacy Gillis, Newcastle University: “The Child is father of the Man,” as Wordsworth’s famous axiom goes. The Bildungsroman, narratives that trace the relationship between child and adulthood, certainly has a long-standing, if never subtle, presence in the history of the novel in English. It can be traced back through Jane Eyre to the origins of the novel with Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722).

Hanya Yanagihara’s Booker-shortlisted A Little Life (2015) should be located within this somewhat creaky tradition. The protagonist Jude’s early life, initially teasingly and then increasingly abruptly, is positioned in counterpoint to the adult Jude’s negotiation of relationships. The effects of childhood abuse, neglect and terror are played out in these relationships, in which Jude both finds great love and, at times, struggles to understand his place within.

This fascination with self-discovery is a necessary part of the Bildungsroman narrative, but has also been exacerbated by the now century-old popular fascination with psychoanalysis. Nothing, surely, can be more interesting to others than one’s own self-discovery. Jude is in the first year of law school when “his life began appearing to him as memories”: “A scene would appear before him, a dumb show meant only for him.”

But Jude’s self-interest is something which we as readers will excuse, in the aftermath of the last 20 years of child abuse memoirs and fictions, because of the abuse he has sustained. His adult self is punctuated by scenes of horrific abuse which are elegantly and described in a Nabokovian way:

A month ago, after a very bad night – there had been a group of men, and after they had left, he had sobbed, wailed, coming as close to a tantrum as he had in years, while Luke sat next to him and rubbed his sore stomach and held a pillow over his mouth to muffle the sound.

The domestic quietude evoked by the rubbing of his stomach, juxtaposed with the threat of the pillow, underlines the fraught emotional sinews which bind abused and abuser. These bonds that tie, and connect, and connive, are at the heart of the child Jude’s novel.

The horrific accounts of the abuse which Jude experiences as a child, and its tentacles coiling through his life, are the most difficult passages to read. In an age in which, we are told, a few clicks of the mouse can bring us face-on with visual evidences of this kind of abuse, to be able to evoke nausea and disgust through the written word is remarkable. More often than not, abuse on this scale (scale not only in act but also in description) does not make it to the pages of the mainstream novel, and rarely into a novel that has been feted with literary approbation.

But it is the sinews of other relationships which mark this novel as more than just one more of the child abuse memoirs and fictions which now populate booksellers’ must-reads. This is a novel about male desire in some of its forms, and the grotesquely described accounts of male-male child sexual abuse are part of this spectrum of emotionality between men. Yet it is in friendship between men that Jude gains a sense of himself as an adult, and as someone who can contribute (however little he may recognise this or, more vitally, value it) to others’ lives. This is all the more important given that this is often an overlooked relationship in the 20th-century novel, presumably partly a response to the multiple dissections of friendships between women in the novels of the long 19th century.

The opening pages of A Little Life are reminiscent of Donna Tartt in setting, and there are some muted hedonisms which nod towards Easton Ellis: fresh from university, a group of male friends make their way in the big city. Much is made of the promise of these young men when they come to the city, and they do not disappoint, at least in terms visible to those who know them superficially.

Here Yanagihara plays with readers’ expectations around the tropes of “literary” fiction: in a novel which is more attuned to the realities of experience, one would expect some of these men to fall, and even to fall spectacularly. But they do not, and each becomes tremendously successful in their professional lives. If Jude’s childhood has hallmarks of the gothic, then these young men, leaving the sanctuary of the gilded halls and heading into the success of life in the big city, are more in tune with the fairy tale.

History of letters

These nods to the history of the novel in English are no accident. A Little Life is rooted in the past: both the individual history of Jude, but also the history of the novel in the English language. Yanagihara is well aware of the Bildungsroman, of the fairy tale, and of the gothic. There is the southern American gothic – as Jude is bundled around Texas and used by redneck truckers for sex – and the English gothic. The abandoned child, the possible and very real terrors within the domestic, and the devilish monk, Brother Luke, who is Jude’s abuser, pimp and carer, all feature in many Gothic novels from Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796) onwards.

One of Jude’s friends, JB, refers to Jude as the Postman – post-sexual, post-racial, post-identity, post-past. This is a knowing nod to the seasoned reader of contemporary fiction, a reader aware of the edges, at least, of the discussions about postmodernism.

But the reference to the Postman also has a particular place in American popular cultural history. The critical and commercial failure of The Postman (1997) ended a decade-long run of Hollywood success for Kevin Costner. A saccharine post-apocalyptic film which now has a cult following, the Postman rebuilds a society through small connections he makes with others, and which he helps others make with one another. The film’s ending implies that the Postman was not able to live through to see the effect of his work, but that he is remembered with love and hope.

There is love and hope in A Little Life as well – of hope left by the knowing of someone, of being friends. The hope also of loving one another well enough, although perhaps not the complete love that we might have desired.

There is no narrative redemption for Jude, no fairy-tale ending, which child abuse memoirs and fictions often evoke. A less deft novel might have given Jude a less obscure winding down of his life, but Yanagihara is confident enough to show that even fleeting and transitory moments of love and happiness can be enough, that that the act of friendship can be the most important act in one’s life.

|

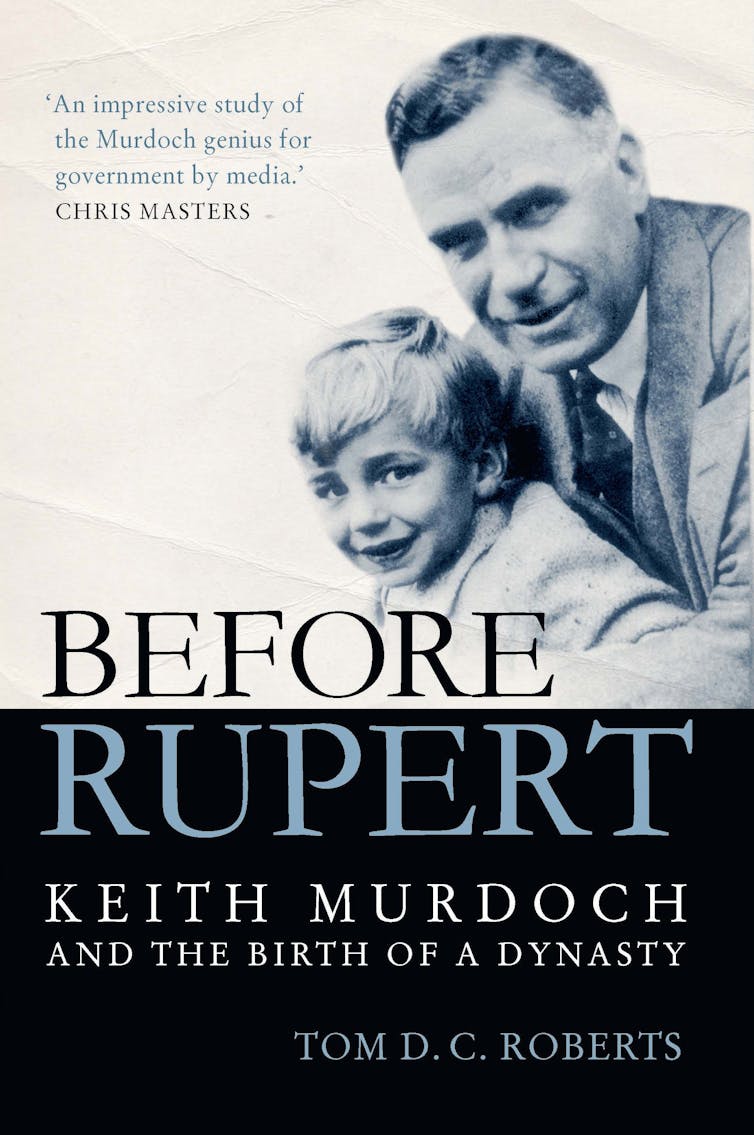

Before Rupert – Keith Murdoch and the Birth of a Dynasty

Peter Cochrane, University of Sydney: Keith Murdoch might have followed his father into the ministry of the Free Church of Scotland but the stammer that would dog him all his life put paid to a career in the pulpit. Instead he chose journalism, and thereby hangs a tale.

Prior to Tom D.C. Roberts’ independent scholarship there were three biographies of Keith Murdoch commissioned by the family – two of which were published, being more flattery than biography. There was a book by John Avieson that was never published; there was a careful, pared-back entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography written by Geoffrey Serle; and there was not much else.

The myth spun around Murdoch held tight for a long time. He was the man who, by dint of hard work and talent, rose from lowly reporter to become a selfless journalist in the service of the public good and subsequently the head of the largest media group in Australia.

And Murdoch was the author of the “Gallipoli letter”. He was the Australian war correspondent who fearlessly exposed the debacle and tragedy of Gallipoli in a scathing exposé that brought about the evacuation of the Anzacs from the Gallipoli peninsula.

But Murdoch did not suggest evacuation in the famous letter. That was the myth holding tight. Roberts notes with some pleasure that:

… critical engagement with a life otherwise accepted as written has the potential to yield rich new information and perspectives, most particularly on those who have sought to frame and protect a particular view of the past.

This book busts that frame. It is a comprehensive biography, gifting to readers a new understanding of Murdoch and the genesis of his family dynasty. The subject is thoroughly yet fairly interrogated and the life richly contextualised, particularly with reference to journalism, high politics and the technological advances that Murdoch was quick to add to his newsprint business – notably radio, newsreels and air travel.

The Gallipoli letter catapulted Murdoch into the high politics of wartime London. At 30 he was hobnobbing with men of great power and influence, and was determined to be a power in his own right. The book is a detailed account of how he did it, how he “ruthlessly exploited his networks to gain ultimate control over Australia’s media and political landscapes” and, contrary to the myth, bequeathed his son Rupert far more than a single provincial newspaper.

But riches can be intangible. What Keith left Rupert, apart from the wealth and a world of connections in high places, was a template for remorseless expansion. The full meaning of this legacy builds slowly – step by step – as the narrative reveals what a clone is Rupert. The book could well have been called The Murdoch Gene.

The parallels between the Keith Murdoch press’s disgraceful coverage of the Gun Alley murder case (1921-22) and the News of the World phone-hacking scandal (2002-11) are utterly chilling. But that’s a mere fragment of a lifelong and still evolving pattern.

Roberts has rightly taken a keen interest in the hitherto unexplored roots of Keith Murdoch’s relentless pursuit of worldly riches and temporal power. He finds these roots in Murdoch’s passionate Social Darwinism – manifesting in the first instance in his professed need to “struggle” and be “very fit indeed”, maturing in the first world war into a white race evangelism, the elevation of racial purity into “the sacred object” (to quote Murdoch) and his slightly later commitment to eugenics, which he reaffirmed after the second world war.

Murdoch’s racial passions took expression in his near-worship of the Anzacs’ bodies, in his promotion of female beauty competitions and, strangest of all, “The Best Baby in the British Empire” competition in 1924.

Readers were asked to submit “unclothed and full-length” photographs of their children. The shortlist for the London stage of the competition was to be subjected to “medical testimony” on their physical features. The Australian judging panel was headed by the vociferous eugenicist R.J. Berry.

The winner was “little Pat Wilson” from Melbourne. “Little Pat”, with her “milk-white skin” had triumphed over 60,000 other competitors. Roberts appears not to have inquired as to the racial composition of the various shortlists and the finalists, other than “little Pat”. Perhaps we can guess the answer?

Roberts charts Murdoch’s rapid creation of a newspaper empire, his corporate wheeling and dealing, his great and powerful friends (Lord Northcliffe, Beaverbrook, W.L. Bailleu), his eagle eye for the advantage to be exploited in new technologies and his transition into the role of “kingmaker”, a man powerful enough to make and unmake cabinets, governments and even prime ministers.

Quite a story, quite a template, for son Rupert.

Keith Murdoch rarely failed, but one or two failures were spectacular. His second attempt to unmake a “king”, after contributing to General Sir Ian Hamilton’s recall from Gallipoli, remains infamous. He was part of a small cabal – including C.E.W. Bean – intent on removing Major General John Monash from the Western Front, putting him behind a desk in London and replacing him with Major General Brudenell White. The plot failed.

Monash made his resentment plain in a letter to his wife, nine days before the crucial battle of Hamel – which would prove to be a masterstroke of his generalship:

It is a great nuisance to have to fight a pogrom of this nature in the midst of all one’s other anxieties.

The Monash vignette is but a small part of Roberts’ rich account of Murdoch’s role in the war as chief propagandist for Prime Minister Billy Hughes, chief “sooler-on” in the recruitment and conscription campaigns, chief race patriot and otherwise tireless climber.

Murdoch’s origins in devout Calvinism never quite left him, or at least remained as polite cover for his more base instinct and purpose. He frequently expressed this purpose in terms of good works in the public interest or epistles about honesty and disinterested truthfulness. But as Roberts points out, it is in his private directives to his lieutenants, such as Lloyd Dumas, that we see a more candid Murdoch and, again, the template evolving. He wrote in February 1930:

We want crime, love, excitement and sensation. More of these essentials are undoubtedly required even to maintain sales.

Murdoch wanted:

… romance, mystery, crime – all three and plenty of them!

Roberts has crafted a fine biography, full of remarkable insights into a central figure in Australian corporate and political history, a figure hitherto enveloped in family mythology, a figure whose chief legacy – a chip off the old block – is still hard at work everywhere, but mostly in New York.

Peter Cochrane, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney, This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|

Our Brilliant Friend

In her Neapolitan series, Italian novelist Elena Ferrante frees herself from having to create heroic characters

By Arshia Sattar: HOWEVER UNKNOWN Elena Ferrante might have been in India a month ago, the recent ‘outing’ of the real person behind the nom de plume has made sure that she exploded onto the horizons of literary people in our part of the world. This article is not about that, it’s about the books that made Elena Ferrante famous, those marvelous books that ignited the curiosity of some of her readers about who she might be in real life. No doubt because she constructed believable characters with such deft confidence in her four Neapolitan novels, some people wondered if and how that real life impinged upon or inspired or was reflected in her work. Personally, I couldn’t care less.

The Neapolitan novels have a first person narrator, (E)Lena, and she recounts (in the first book, My Brilliant Friend) her own childhood in the grinding poverty, pervasive misogyny and ubiquitous violence of post-War Naples. Her best friend is Lina (but Lena calls her Lila and that’s how we know her), a charismatic, wild and fearless creature, bright and sharp-witted, who pulls the more timid Lena forward into exploring the frightening parts of the neighbourhood as well as into adventures of the mind and heart. Through the next three novels and five decades, Lena and Lila duck and weave through one another’s lives, dragging their trials and triumphs, their loves and hates along with them, challenging each other, holding each other up, rescuing each other from demons within and without. Apart from the fact that the relationship between these two women is utterly compelling in its pendulum of love and hate, Ferrante draws the reader into the novels by stacking their emotional and physical landscape with a host of complex and finely drawn characters who stay with our protagonists through their lives. For example, even though Don Achille dies in the first few chapters of the book, he will linger in readers’ memories as the neighbourhood bogeyman for children and adults alike and his long shadow will stay with us and with the girls until the end. The swaggering, thuggish Solara brothers; the intellectually vapid, emotionally dishonest but irresistible Nino; dogged, loyal Enzo; the mad widow Melina—each of these has a compelling narrative arc of their own and Ferrante is generous in her attention to them. Each of them leaves the neighbourhood in their own ways but the question that remains till the very end is if the neighbourhood ever left them. Any one of them.

Through sheer dint of hard work and a few strokes of good fortune, Lena is able to continue studying and get away to university from where her life rises steadily towards literary success and becomes filled with various bourgeois conceits. Lila is left behind in the old neighbourhood where she marches, always alone, to the beat of a distant drum. As her rebellion verges on self-destruction, her thoughts remain inscrutable and the choices she makes for marriage and love hurl her headlong into a series of confrontations with her men and with the world around her. Lena spins herself into a tight little cocoon of safety, but Lila appears to unravel as she tries to protect herself from the brutality and squalor that surrounds her. Lena makes apparently rational choices while Lila rides a cresting wave of passion, the depth of whose trough is inevitable. But what holds the reader is not only Lila’s outrageous charisma, but also Lena’s quiet, almost desperate struggle to rise above her circumstance. You are never sure which of these growing young women is stronger, which more foolish, which one more false to the person she truly is. There are times when you hate Lila for her cruelty, her utter self-centredness, her reckless spiral into penury and degradation. But over the course of her life, you begin to see that her bloody fight is essentially for truth and justice. Lila lives the politics, both leftist and feminist, that Lena learns about and discusses with her university peers.

The Neopolitan novels are not easy books to read, even the happiest moments are shadowed by anxiety, fear, revenge and greed

Ferrante provides a lush picture of the turbulent times in which these young girls grew into women. She does that through letting national events and world movements seep into the lives of the young people she writes about. The Solaras become hit-men for a Fascist political party, Pasquale and Nadia become fugitives because they are part of the extreme left-wing groups that challenge the status quo in Italy in the 1970s, the girls from Lena’s childhood barter their sweet young selves in marriage for wealth and protection as a brash materialism rises from the dying embers of the old world. Lena herself finds a new voice as a feminist writer as her personal life, in terms of balancing her children and her lover and her husband and his mother, is in tatters. In each of these crises, it is Lila who makes a critical intervention. No one from her past is able to escape her aura or the subterranean ways in which she wields her mysterious powers. But Lila’s own life is far from calm or prosperous. Her body ravaged by difficult pregnancies and violent beatings, her heart splintered by love, Lila protects the one thing she owns completely— her fine and incisive mind which lets her teach herself about computers but is also her sharpest weapon in her battle against the hypocrisies that surround her. Despite all that happens to her and the places into which she pushes herself, we are still completely unprepared for the utterly random event that closes the last book, The Story of the Lost Child, and completes the tragedy that has always been Lila’s life.

The Neapolitan Novels are not easy books to read. Even the happiest moments in the story are shadowed by anxiety, fear, jealousy, revenge and greed. Small victories do not last long, successes are poisoned in the very moments of their birth, loves are rotten at the core, children become pawns and men are destroyed as frequently as women by the emotional and physical violence that pervades this brutal world. What Ferrante shows us is how violence corrupts the innermost core of a human being. Perpetrators of violence carry the mark of Cain upon their souls, a mark which becomes a canker eating away at whatever might once have been good or noble. But those who live around violence and are spectators to it are also scarred, their own skin curling and deformed, closing around the wounds they share with its direct victims.

Why then, does Ferrante compel us so, with her cruel worlds and her dark hearts and her people mostly beyond redemption? It’s not as if her protagonists, the oddly twinned Lena and Lila, are beacons of light or hope. Perhaps this is precisely where we recognise that Ferrante tells the truth about human beings, that she is free of narrative vanities that demand the creation of heroic characters who rise above their circumstances and leave the reader with a sense of lightness of possibility, of human goodness, a final sigh of either spiritual or existential relief. As in her earlier work, Days of Abandonment , for example, here too, Ferrante is unflinching and fearless: there is no place inside her characters, neither in their bodies nor in their souls, for which she will not reach, no dead child nor dead dream that she will not exhume. And yet, in the Neapolitan sequence, you sense the immense control she exercises over herself, stopping just short of tipping her characters over into the abyss of grotesque melodrama and unreachable pain. She is a writer in full command of what she wants to do and of how she wants to do it. Her earlier works were dress rehearsals, essentially, for the virtuoso performance she unleashes in the Neapolitan novels.

Ferrante is unflinching and fearless: There is no place inside her characters, neither in their bodies nor in their souls, for which she will not reach

I am compelled by Ferrante because she speaks to me as a woman about women. But because she speaks about women so fully and richly in her many and varied characters, she is also talking about (and to) men. Men are a part of her narrative universe, but they are equally a part of the world she addresses as a writer. And so I wonder that even though there is no aggressive feminism or ‘womanism’ in her work, the many men I know who enjoy Ferrante, do not read her in the kind of manic frenzy that women do. She seems to touch something in women that I, as a woman who reads women with great pleasure, have certainly never felt before. It’s not as complicated as telling a woman’s story well, so many women (and some men) writers have done that with great elegance before her. It’s also not as simple as speaking across cultural particularities to all women in all places, calling on resonances in experience and emotion to create an empathetic reading space. Of course, Ferrante does both those things and she does them with ease. But there is something more than that, something primal almost, something hitherto unexplored with such tenacious determination. It could be that women respond to Ferrante more keenly because we, too, are caught in the glare of her clear-eyed ferocity, her unwillingness to compromise on describing how women experience the world and their place in it. We submit ourselves to her, allowing her, as her characters do, to reach within us and wrench our gut, recognising a visceral rather than a cerebral or literary truth about our being as women.

FERRANTE HAS BECOME the touchstone for what I now want from women who write about women. I have not recovered from reading her, but I have also learned to approach her work with caution—I am not always ready to have my gut wrenched, my living beating heart dissected, my soul laid bare, exposed to the bright light of day and the gaze of others.

As with other life-shaping experiences, I must recall that epiphanic moment when I first read Ferrante, for she has become a talisman against falsehood in my own writing. I encountered her a few summers ago and was warned by the friend who gave me the first book that I would not be able to put it down. She was right, I couldn’t. And even as I was half way through that first mad rush of blood to the head and the heart, I made sure that the next volume, The Story of a New Name, was close at hand. That summer, it seemed as if every woman I knew was reading Ferrante, all of us trading notes about what was happening in the story. We confessed (a little sheepish, but not at all guilty) how we surrendered to the sheer force of the novels, ignoring work and play and partners, pets and children, food and even sleep. Each of us was a Ferrante evangelist, urging her books on to others, ensuring that whoever was reading had access to the next novel. For the thousands of us who read her like addicts, it is only the books that matter. We couldn’t care less who Elena Ferrante is, for she is completely and will always be, our Brilliant Friend. She knows us as no one else can. She holds our secrets in the palm of her hand. And we trust her with them. Not because she will not tell, but because when she tells, she will elevate them from being our personal, petty concerns to being a narrative about the fundamental female (rather than the human) condition. Brava, Elena! My understanding of myself would be less without you. Source: OPEN Magazine

|