Peter Cochrane, University of Sydney: Keith Murdoch might have followed his father into the ministry of the Free Church of Scotland but the stammer that would dog him all his life put paid to a career in the pulpit. Instead he chose journalism, and thereby hangs a tale.

Prior to Tom D.C. Roberts’ independent scholarship there were three biographies of Keith Murdoch commissioned by the family – two of which were published, being more flattery than biography. There was a book by John Avieson that was never published; there was a careful, pared-back entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography written by Geoffrey Serle; and there was not much else.

The myth spun around Murdoch held tight for a long time. He was the man who, by dint of hard work and talent, rose from lowly reporter to become a selfless journalist in the service of the public good and subsequently the head of the largest media group in Australia.

And Murdoch was the author of the “Gallipoli letter”. He was the Australian war correspondent who fearlessly exposed the debacle and tragedy of Gallipoli in a scathing exposé that brought about the evacuation of the Anzacs from the Gallipoli peninsula.

But Murdoch did not suggest evacuation in the famous letter. That was the myth holding tight. Roberts notes with some pleasure that:

… critical engagement with a life otherwise accepted as written has the potential to yield rich new information and perspectives, most particularly on those who have sought to frame and protect a particular view of the past.

This book busts that frame. It is a comprehensive biography, gifting to readers a new understanding of Murdoch and the genesis of his family dynasty. The subject is thoroughly yet fairly interrogated and the life richly contextualised, particularly with reference to journalism, high politics and the technological advances that Murdoch was quick to add to his newsprint business – notably radio, newsreels and air travel.

The Gallipoli letter catapulted Murdoch into the high politics of wartime London. At 30 he was hobnobbing with men of great power and influence, and was determined to be a power in his own right. The book is a detailed account of how he did it, how he “ruthlessly exploited his networks to gain ultimate control over Australia’s media and political landscapes” and, contrary to the myth, bequeathed his son Rupert far more than a single provincial newspaper.

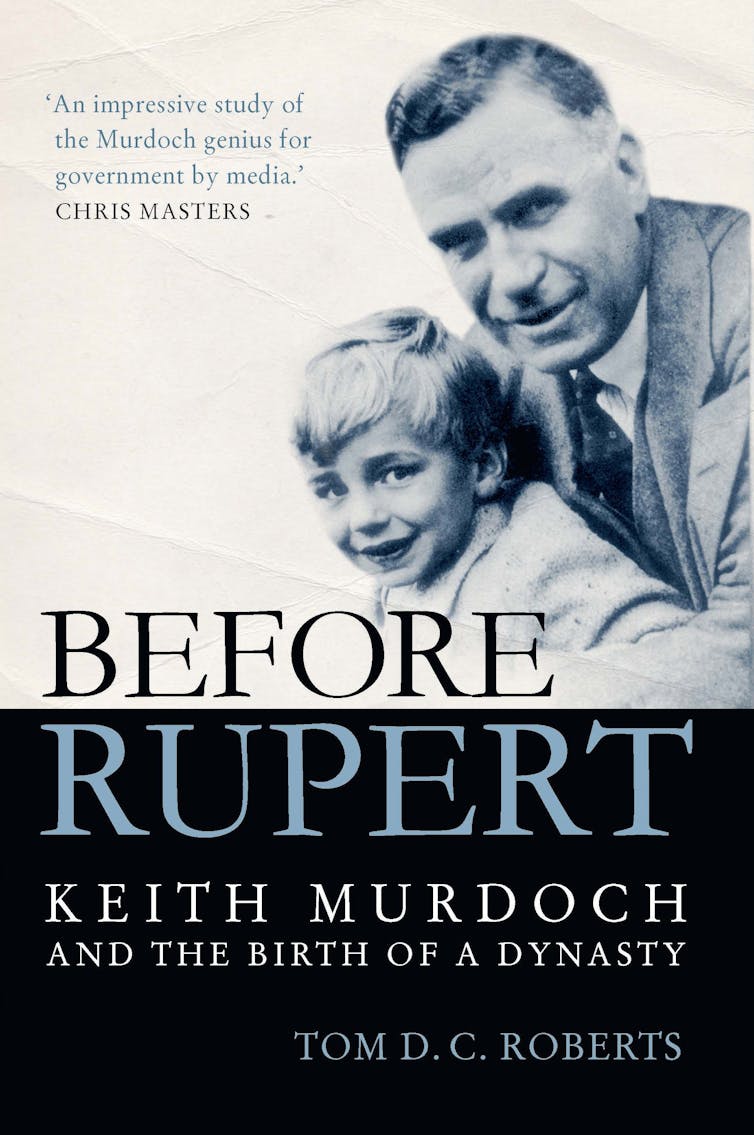

But riches can be intangible. What Keith left Rupert, apart from the wealth and a world of connections in high places, was a template for remorseless expansion. The full meaning of this legacy builds slowly – step by step – as the narrative reveals what a clone is Rupert. The book could well have been called The Murdoch Gene.

The parallels between the Keith Murdoch press’s disgraceful coverage of the Gun Alley murder case (1921-22) and the News of the World phone-hacking scandal (2002-11) are utterly chilling. But that’s a mere fragment of a lifelong and still evolving pattern.

Roberts has rightly taken a keen interest in the hitherto unexplored roots of Keith Murdoch’s relentless pursuit of worldly riches and temporal power. He finds these roots in Murdoch’s passionate Social Darwinism – manifesting in the first instance in his professed need to “struggle” and be “very fit indeed”, maturing in the first world war into a white race evangelism, the elevation of racial purity into “the sacred object” (to quote Murdoch) and his slightly later commitment to eugenics, which he reaffirmed after the second world war.

Murdoch’s racial passions took expression in his near-worship of the Anzacs’ bodies, in his promotion of female beauty competitions and, strangest of all, “The Best Baby in the British Empire” competition in 1924.

Readers were asked to submit “unclothed and full-length” photographs of their children. The shortlist for the London stage of the competition was to be subjected to “medical testimony” on their physical features. The Australian judging panel was headed by the vociferous eugenicist R.J. Berry.

The winner was “little Pat Wilson” from Melbourne. “Little Pat”, with her “milk-white skin” had triumphed over 60,000 other competitors. Roberts appears not to have inquired as to the racial composition of the various shortlists and the finalists, other than “little Pat”. Perhaps we can guess the answer?

Roberts charts Murdoch’s rapid creation of a newspaper empire, his corporate wheeling and dealing, his great and powerful friends (Lord Northcliffe, Beaverbrook, W.L. Bailleu), his eagle eye for the advantage to be exploited in new technologies and his transition into the role of “kingmaker”, a man powerful enough to make and unmake cabinets, governments and even prime ministers.

Quite a story, quite a template, for son Rupert.

Keith Murdoch rarely failed, but one or two failures were spectacular. His second attempt to unmake a “king”, after contributing to General Sir Ian Hamilton’s recall from Gallipoli, remains infamous. He was part of a small cabal – including C.E.W. Bean – intent on removing Major General John Monash from the Western Front, putting him behind a desk in London and replacing him with Major General Brudenell White. The plot failed.

Monash made his resentment plain in a letter to his wife, nine days before the crucial battle of Hamel – which would prove to be a masterstroke of his generalship:

It is a great nuisance to have to fight a pogrom of this nature in the midst of all one’s other anxieties.

The Monash vignette is but a small part of Roberts’ rich account of Murdoch’s role in the war as chief propagandist for Prime Minister Billy Hughes, chief “sooler-on” in the recruitment and conscription campaigns, chief race patriot and otherwise tireless climber.

Murdoch’s origins in devout Calvinism never quite left him, or at least remained as polite cover for his more base instinct and purpose. He frequently expressed this purpose in terms of good works in the public interest or epistles about honesty and disinterested truthfulness. But as Roberts points out, it is in his private directives to his lieutenants, such as Lloyd Dumas, that we see a more candid Murdoch and, again, the template evolving. He wrote in February 1930:

We want crime, love, excitement and sensation. More of these essentials are undoubtedly required even to maintain sales.

Murdoch wanted:

… romance, mystery, crime – all three and plenty of them!

Roberts has crafted a fine biography, full of remarkable insights into a central figure in Australian corporate and political history, a figure hitherto enveloped in family mythology, a figure whose chief legacy – a chip off the old block – is still hard at work everywhere, but mostly in New York.

Peter Cochrane, Honorary Associate, Department of History, University of Sydney, This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|