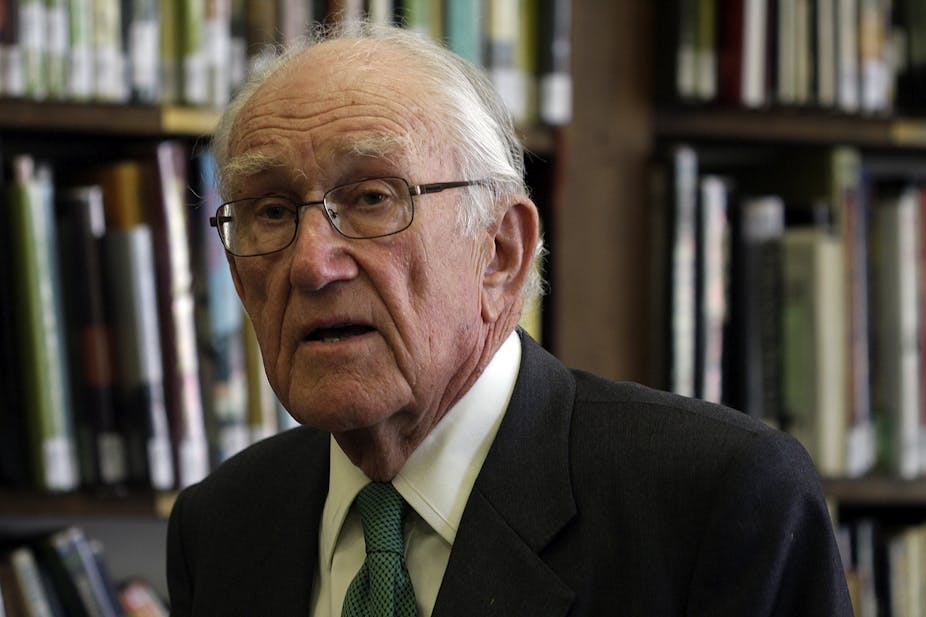

Mark Beeson, Murdoch University: Malcolm Fraser occupies a rather unique place in Australia as someone who has, at different times, managed to incense both ends of the political spectrum. If nothing else this is indicative of someone who has a capacity to change his position over the course of a lifetime. Fraser’s new book, Dangerous Allies, seems certain to cement his place as an unexpected, late-blooming radical.

The content of Dangerous Allies will be familiar to anyone who has taken an interest in Fraser’s recent career as a polemicist and public intellectual. The principal focus of this book is Australia’s relationship with the United States, and what Fraser describes as the associated dangers of “strategic dependence”.

Simply put, this is a consequence of the belief that Australia’s security is best guaranteed by the cultivation of what former prime minister Robert Menzies famously described as “great and powerful friends”.

Fraser’s argument is that while strategic dependence may have been understandable and defensible during the early years of Australia’s post-colonial history and the Cold War, it is now a liability, and a potentially dangerous one at that. Whatever one thinks of Fraser’s arguments in favour of this position, the chapters devoted to these periods are impressively scholarly and – especially in the more recent periods – enlivened with anecdotes of the when-I-spoke-to the-president variety.

One of the reasons this book is likely to upset so many on the conservative side of politics is not simply because Fraser adopts such an iconoclastic attitude toward the centrepiece of Australian security policy for more than half a century, but because he’s scathing about the some of the icons of the Liberal Party, too.

Menzies suffered from a “great misunderstanding” about the importance of Britain, Fraser contends, while Howard further entrenched the culture of strategic dependence on the US to the detriment of our regional relations.

By contrast, Fraser gives some Labor luminaries such as Gough Whitlam and especially Doc Evatt great credit for attempting to carve out a more independent foreign policy. The current generation of Labor leaders, however, suffer from the same “bipartisan failure” that has circumscribed our capacity to make separate strategic decisions from the US. The net result, Fraser argues, is that:

We have significantly diminished our capacity to act as a separate sovereign nation.

No doubt the present government – and opposition, for that matter – will dismiss such claims out of hand. So too will the great majority of strategists in Canberra, be they military or civilian. But Fraser is surely right to question the supposed benefits that have accrued to Australia from participation in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Significantly, Fraser is more equivocal about Vietnam (where he had ministerial responsibility), although much the same could have been said about that conflict too.

Although Fraser judges that America’s involvement in Vietnam was an “unmitigated failure”, he also concedes that it was a commitment he “fully supported”. His justification for what he now sees as a misjudgement was that the US was either “derelict in their duty to inform us of the true situation” or “deceitful”. He is even more scathing about America’s preparedness to “murder” former political allies when it suited them.

What faith can a nation have in an ally that believes it is within its right to remove the nation’s head of state?

It’s a good question, and one that might have been addressed to Australia’s own constitutional coup and the rumours that persisted about CIA involvement in Whitlam’s downfall. Of this possibility, however, there is notably no mention. Being in the thick of it, so to speak, is something else that exercises a constraining effect.

If there is one thing that this book serves to demonstrate it is just how difficult exercising independent thought and action actually seems to be when in office – particularly as far as relations with the US are concerned. Although Fraser now admires New Zealand’s “far-sighted and correct” independent foreign policy, while inside the Canberra bubble he dutifully joined the chorus of condemnation.

While I am sympathetic to many of the arguments Fraser develops, I have no expectation that they will have the slightest impact in Canberra. I have been making a similar argument about the possible benefits of a more independent, less-aligned foreign policy for more than a decade now, with absolutely no discernible impact on the policy debate, much less on policy itself.

True, I’m not a former prime minister. Fraser’s book will at least be extensively reviewed and discussed. Whether it will it make any difference is another question.

It is possible to quibble with a number of aspects of the book, even if one is not overtly hostile to its core idea. Fraser’s faith in the diplomatic capacities of the ASEAN states, especially as far as China is concerned, looked overly optimistic even before the latter’s more aggressive pursuit of its territorial claims.

Similarly, Fraser’s suggestion that defence spending is likely to rise as the price of independence is both debatable and unlikely to win converts to the cause. New Zealand might still have lessons to offer in this context.

Nevertheless, this is one of the most original and timely contributions to a debate that, with a few honourable exceptions, tends to be sterile, predictable and unchanged since the end of World War Two.

As Fraser points out, the world has changed profoundly in the interim. It’s about time some of our thinking began to reflect the new realities, too, he suggests. An independent Australia could actually play a useful role in doing precisely that.

|

Book review: Dangerous Allies by Malcolm Fraser

Selling Apartheid – South Africa's Global Propaganda War

Peter Vale, University of Johannesburg: In the face of mounting of international disapprobation, how did white rule in South Africa sustain itself?

Ron Nixon tries to answer this question in Selling Apartheid – South Africa’s Global Propaganda War. He is a Washington correspondent of the New York Times and an associate of the department of Media and Journalism Studies at Wits University. Unfortunately, his book disappoints.

As the title suggests, Nixon believes that apartheid South Africa “sold” – rather than “told” – its story to the world. His narrative draws from three sources: published work, several interviews, and a peek into (mainly) American archives. His technique is the case study.

So he uses the exemplar case of apartheid’s “unorthodox diplomacy” – the well-documented Muldergate scandal of the 1970s. Its infamy was heightened by the fierce interdepartmental rivalry it generated. It also ended the careers of the then-prime minister, John Vorster, and Connie Mulder, the influential information minister. Mulder was considered to be next in line for the top job.

The conspiracy aimed to buy newspapers in the US with taxpayers’ money. Through these, apartheid’s cause would be promoted in an America in which the issue of human rights was increasingly drawn towards the foreign policy debate. South Africa aimed to tap into a counter-narrative that eventually led to the Reagan presidency, the rise of free market economics, and the “second” Cold War.

As Nixon points out several times, the events that culminated in Muldergate were spearheaded by a 30-something former journalist and sometime government information officer. His name was Eschel Rhoodie, a controversial character in any book.

Dubious characters peddling apartheid

The Paper Curtain, a polemic Eschel Rhoodie wrote, seemingly was the text that enabled South Africa’s traditional diplomacy, modelled on formal state-to-state practice, to change into a policy of buying influence in high places in Washington and other Western capitals.

When the Muldergate ruse was exposed, Rhoodie fled and purported sightings of him came to overshadow the scandal itself. Intrepid South African pressmen finally tracked him down in Ecuador. The occasion was marked by a photograph of him feeding a llama, on the front page of the then-Rand Daily Mail.

Nixon has used the seminal account of Muldergate, written by journalists Mervyn Rees and Chris Day, as the basis for his version of the story. So, on the Muldergate case, there’s very little new in the book.

In presenting another case, Nixon turns to another contentious character – Max Yergan, a Black American activist who arrived in South Africa in 1922 to pursue a career in the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

Posted to Alice, in the Eastern Cape, Yergan became close to many who would play a role in South Africa’s liberation – John Tengo Jabavu, John Langalilele Dube, Alfred Xuma, ZK Matthews and Govan Mbeki.

Ostensibly monitored by the state’s security apparatus, Yergan gradually lost his faith in Christianity (and in the work of the YMCA) as a force for liberation. During a visit the Soviet Union in 1934, he embraced Marxism. Unsurprisingly, his South African friends found him a “changed” man when he returned to this country.

Three years later, and back in the US, he set up (and served) on various bodies that were the precursor to the worldwide anti-apartheid movement. In these spaces, Yergan rubbed shoulders with legends of Black American culture and politics: actor Paul Robeson, Nobel Laureate Ralph J.Bunche, and pan-African intellectual W.E.B du Bois.

But Yergan’s political star was to crash, as the Cold War took hold, in a brutal argument with Robeson. This conflict drove Yergan back towards South Africa in the form of a newly found anti-communism. This was the official Cold War position of the government in Pretoria that he had once so strongly opposed.

In the 1940s Yergan made several visits to South Africa that were cleared by the FBI and sanctioned by the white government. During the course of these, Yergan and his fierce anti-communist views were spurned by the African National Congress, South Africa’s liberation movement, and by the South African Communist Party.

Eschel Rhoodie. The Star

If efforts by white power to directly buy influence in the world – as in the Rhoodie instance – is one case in Nixon’s book, another – represented by the Yergan example – was the failure of Black Americans to understand that they too could be tricked by the persuasive power of the white purse.

Where books fails and succeeds

But – and this is a failure of the book intellectually – the comparative value of these two cases, and others of similar ilk in the book, is of limited value. They are not thought through.

Nixon is strongest, empirically, when he is working the Washington patch: his access to individuals and to archival sources has brought several fresh issues to the fore. That said, he is weak on American policy towards apartheid South Africa and how this issue was linked to decolonisation in the subcontinent.

So, the important role of Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State under Richard Nixon, in the making of America’s African policy is poorly considered. When he was US national security advisor, Kissinger was responsible for what was famously called the “Tar Baby” option – America’s policy tilt to governments in Africa’s “white South” and intentionally away from the majority-ruled countries.

This move, more than any other factor, opened the way for Vorster’s government to “sell” its wares to the US and – as Nixon also claims – to its European Cold War allies. Unfortunately, as the focus moves towards these places, the empirical evidence weakens, and speculation drives the story.

Let’s be clear: there is no doubt that successive apartheid governments spent millions (and much energy) cosying up to political parties (and the great-and-good that support them) in the UK, and in Europe. But the deep evidence for this, as presented in these pages, is a thin, thin reed.

There is an important and interesting book to be written on the apartheid’s efforts to peddle its story through unorthodox diplomacy, but this is not it.

Peter Vale, Professor of Humanities and the Director of the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study (JIAS), University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|

Book review: The Lost Legions of Fromelles

Peter Stanley, UNSW Australia: Almost exactly 98 years ago, the Fromelles legend goes, the 5th Australian Division was thrown into battle by stupid British generals and slaughtered. Overnight, 5500 men were killed or wounded: supposedly the single worst day in Australian military history.

In the battle, supposedly forgotten, Australian diggers displayed the familiar but timeless virtues of courage and mateship. Despite the supposed cover-up, in 2007 a mass grave was found, thanks to the persistence of amateur researchers, and today the story is told in the newest Great War cemetery at Fromelles.

Needless to say, the popular legend is not entirely true. It omits as much as it includes and gets wrong as much as it reveals.

British historian Peter Barton’s The Lost Legions of Fromelles tells what is to an extent a familiar story – of slaughter in the ditches and marshes of no man’s land – but it adds to both what we know and how we should be wary of the popular legend.

While not a flawless book – it’s about twice as long as it needs to be, for a start – this is an important book for Australians. Its primary virtue is that it is based on German – specifically Bavarian – sources that extend and refine the familiar Australian story.

Corporal David Frederick Livingston is one Australian soldier now honoured at the Fromelles cemetery. AAP/ADF

One of the besetting faults of Australian military history as it is practised in the first decades of the 21st century is that it is largely Australian military history. As Barton shows, what Australians call the battle of Fromelles was actually the third battle fought over that ground over two years – and the previous (British) attack also failed, with much the same losses as the Australian attack.

Barton’s detailed book is superior to the emotive, partisan accounts offered to Australian readers, notably by Patrick Lindsay and Les Carlyon. Drawing as it does on “enemy” sources for the first time, it fills in the gaps on the other side of no man’s land.

Crucially, Barton uses the Bavarian archives to show how the corpses of “English” dead were buried in the mass grave at Pheasant Wood out of which the new cemetery has been formed. One revelation is that the graves supposedly “lost” – that is, missed by inept Australian searchers after 1918 – were always fully documented in the abundant Bavarian archives – if only we’d bothered to look.

I have to acknowledge an interest here, as a minor player in one of the “official” committees that rejected the arguments offered by Victorian schoolteacher Lambis Englezos that the mass grave had actually been missed by war graves parties. I was wrong, and said so on the front page of The Australian when it turned out that he had been right. But admitting error once does not mean that I can’t be critical again.

Like a lot of recent military history books, this is too long. Barton gives us far more detail than anyone could want or need. But he’s lazy – it’s easier to quote great slabs of documents than to select and paraphrase – and the give-away is that he is content with giving the initials of men whose names can be found on the internet in seconds. He writes well, especially in describing the processes of research involving sources from several countries and not just documents but archaeological evidence – or “information”, as he insists on calling it.

But none but the most dedicated battlefield nerd will want to know as much as Barton wants to tell. And on points where we need certainty – was the British plan sound? – he never seems to commit himself.

And why call the Australians “diggers”? The word was never used at Fromelles.

Putting these reservations aside, Barton should be congratulated for giving Australian readers a chance to surmount the parochialism that is so common in their military history. As he shows, what happened to the 5th Australian Division had happened before, to British troops.

Thanks to Barton – and some other historians, notably Australian Army historian Roger Lee, whose research on the battle has given us a much clearer understanding of its planning and conduct – the popular legend of Fromelles needs to be revised. Whether he will alter the persistent Australian legend remains to be seen.

Fromelles remains controversial, not least because in recovering the remains the authorities acceded to requests that they try to identify individual corpses. Rather than the dignified anonymous interments accorded to all other Australian Great War dead, the Pheasant Wood saga involved a search for distant relatives, virtually all of whom but for the most obsessive family historians had no idea of their connection to Fromelles or had long accepted that great uncle Jack had been killed there.

No-one seems able or willing to explain why it was necessary to go to these lengths.

And recently we hear that Englezos is at it again, pointing to another mass grave, this time at Krithia, on Gallipoli. Let’s give him a hearing – he has form – but let’s not fall for the story that the dead deserve to be identified or that relatives who didn’t know them need “closure”. It happened a long time ago in a place far away.

Peter Stanley, Research Professor in the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society, UNSW Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|

Book review: Fukushima

Fukushima, by former ABC North Asia correspondent Mark Willacy. Pan Macmillan

Leigh Dale, University of Wollongong: Three years ago today, Japan was hit by the strongest earthquake ever measured in that country – and Fukushima became an international by-word for disaster.

Now, as Japan tries to put its past behind it, Fukushima is back in the news as hundreds of evacuees prepare to return to their homes near the crippled nuclear power plant for the first time next month. But how do any of us begin to understand a disaster that could mean 50,000 people never see their homes again?

ABC journalist Mark Willacy’s Fukushima: Japan’s Tsunami and the Inside Story of the Nuclear Meltdowns is a very good place to start.

On March 11, 2011, off the east coast of Japan’s largest island, Honshu, the sea floor heaved. In the city of Sendai water surged 10 kilometres up the valley of the Abukuma River. Sendai is the largest city in Tohoku, the northern region of Honshu, made up of six prefectures. The tsunami hit hardest in the three prefectures on the east coast: from south to north, Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwate.

ITN shows the moment Japan’s 2011 tsunami hit the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

The Fukushima Daiichi (Number One) nuclear plant, one of several in Tohoku operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), was hit hard by the tsunami. A series of explosions spilled radioactive waste into air and water. The leak has made towns and farmland near the plant uninhabitable: Fukushima prefecture has been devastated.

Mark Willacy’s Fukushima is the story of the tidal wave and the nuclear disaster, told through interviews with farmers, fishermen, teachers, bureaucrats, and the then Prime Minister Naoto Kan.

Willacy opens out a range of views of and reactions to the disasters, the latter ranging from suicide to stoicism to single-minded recreation of a new life. There is a glossary and maps; a “cast list” would have been helpful, although this is offered in part by the captions to photographs.

One of those photographs is a close-up of a woman looking serene, almost smiling; in a second photo she is almost unrecognisable as the intent operator of a mechanical digger. As her story builds, we understand why Naomi Hiratsuka obtained a licence to operate heavy machinery – a way of “doing something”, and of coping with loss.

A picture is developed of what went on inside Fukushima Daiichi: interviewees include a worker who kept notes of key events; the plant manager; the leader of the elite metropolitan fire-fighting team who set up an emergency cooling system amidst deadly radiation; and senior bureaucrats, politicians and company managers in Tokyo, who thought they were calling the shots.

The key factor in the nuclear disaster, as Willacy presents it, was the panic of those senior decision-makers, and their projection of this panic onto the population at large. This projection of hysteria onto those directly or potentially affected by radiation became a rationalisation for secrecy: better to keep others ignorant than alarmed.

The same thinking, coupled with good old-fashioned greed, was at work in the limp or hostile response to warnings by academics about the potential dangers of a tsunami back in 2002, as well as warnings in 2006 about the vulnerability of the plant to inundation.

Willacy’s arrangement of conflicting views reveals a pattern. He shows how those with authority in or over the nuclear industry placed their own profit or equanimity above the lives of others.

The mendacity and malfeasance he reveals are in contrast to the courage and dignity often displayed by those faced with impossible demands, before and during the tsunami and the nuclear crisis.

National Geographic on the 2011 tsunami.

Willacy’s conclusion is that the Fukushima nuclear disaster was “man-made”: not in the sense that nuclear power plants are industrial constructions, but in that the location, design, maintenance, management, and regulatory oversight of the plant were badly flawed, as was the technical and political response to the disaster.

The toxicity of radiation and of lies about radiation is one of two main themes in the book. The other is that “those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it”. The symbol of that idea is a marker stone from an ancient tsunami, below which houses should not be built. The implicit questions: who will read the warnings on the markers? And who will listen to Willacy’s storytellers?

In ordering the story, Willacy has a nice sense of perspective: Naomi Hiratsuka’s grief is as central to this story as the ambition of Prime Minister Kan. But there is a cruel contrast between the anger of the official whose lies or excuses collapse in interview, and the anger of the grieving family member.

I lived and worked in Fukushima for several years in the late 1980s, teaching English mainly at high schools and sometimes at junior highs. Although I have not been back since the tsunami, what is constantly in my mind is the children of those whom I taught, physically and emotionally vulnerable to that radiation and to those lies.

Even if you have never visited Japan, this is a mesmerising story, one I hope more people will revisit, even as memories fade of watching black waves inundate Japanese coastal cities, sweeping away cars, office towers and homes.

Fukushima: Japan’s Tsunami and the Inside Story of the Nuclear Meltdowns by Mark Willacy is published by Pan Macmillan.

|

Book review: Australia Under Surveillance

Lachlan Clohesy, Victoria University: Frank Moorhouse is known primarily – but not exclusively – for his award-winning fiction such as the Edith Triology. In more recent times, he has turned his considerable talents to the role of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) in Australian society in a series of essays.

That research has now spawned a book, Australians Under Surveillance. It is the latest contribution in a field of renewed interest. Debates regarding ASIO have existed since its inception under the Chifley government in 1949.

Today, these debates take two forms. First is the debate about what Moorhouse terms the “legacy” question – the historical role of ASIO, particularly during the Cold War. The second is the questions regarding the powers ASIO should (or shouldn’t) have in what Moorhouse has previously termed a “time of terror”.

Moorhouse begins his latest offering by discussing his own history with ASIO. As a young writer with anarchist tendencies, Moorhouse was a subject of ASIO surveillance. He details the history of ASIO in the surveillance of Australian writers in a Cold War climate which included political attacks on recipients of grants from the Commonwealth Literary Fund by Australia’s would-be McCarthys.

These attacks were often misguided. The vehement anti-communist W. C. Wentworth, for example, was forced into making a humiliating apology to author Kylie Tennant. Moorhouse’s focus is initially on writers. As such, he does not deal with similar attacks, often based on information from ASIO provided improperly to Wentworth and others, on other professions such as scientists and the public service. These also formed part of the Cold War climate which he describes. His discussion of sexual censorship is also illuminating.

The argument quickly moves on to controversial contemporary cases involving Mohamed Haneef and Izhar Ul-Haque. Moorhouse realises – to his credit – that the value of comparison between ASIO’s Cold War legacy and ASIO today is limited:

With communism and sexual issues there was no imminent threat of violence in Australia; with terrorism there is the possibility of a very real threat.

This is a salient point. The reason for ASIO’s existence was to prevent espionage rather than an Australian Bolshevik revolution. Moorhouse’s interview with former ASIO Director-General David Irvine reveals the security service’s current priorities. Irvine says:

My concern is a bombing incident or something that causes mass casualties.

In both areas, however, the debate has moved forward even in the short time since the release of Moorhouse’s book. An official history of ASIO by David Horner, covering the period 1949 to 1963, has also been released, shedding light on ASIO’s Cold War legacy. ASIO’s role in fighting terrorism today has also been highlighted by the tragic events of the Martin Place siege in December 2014.

The value of Moorhouse’s argument lies in his nuanced understanding of ASIO’s role. He accepts the necessity of ASIO’s existence, recognises that terrorism is a significant threat, and at times seems to proffer advice on how to address the historical problems of ASIO’s public image. He cites comments which suggest that ASIO has never enjoyed the public support of its foreign counterparts MI5 or the FBI.

This recognition of ASIO’s importance sets Moorhouse apart from those who are unquestioningly critical of the organisation, including those who have called for its abolition. His “dark conundrum” concerns itself with how such an agency behaves (and is overseen) in a liberal democratic society when the performance of its duties inevitably involves depriving citizens of some of that liberty.

Nevertheless, Moorhouse raises significant and concerning questions about the conduct of an organisation with increasing powers and little oversight. In Australia, the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security has the responsibility for watching over ASIO (and five other agencies). The IGIS, however, employs an ongoing staff of just 12 to watch over an increasingly large national security apparatus.

Moorhouse’s catalogue of cases where he contends rights were infringed or due process ignored is where the links between ASIO in the Cold War and ASIO today can be drawn out by implication. He hints that various raids, computer “cleansing” (the deletion of material by ASIO on computers, including those of publishers and a university professor), legal threats, deportations, media controversies and censorship of literature are intimidatory and contribute to an environment where certain thoughts are seen as dangerous, leading to voluntary self-censorship and the suppression of ideas.

Just as McCarthyism swept up other causes which were not necessarily communist – such as anti-war protests, trade unions, nuclear disarmament and civil rights for Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders – so too the current climate threatens legitimate dissent. This can include, for example, opposition to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, advocacy for asylum seekers, questioning of ASIO’s powers and, potentially, campaigns against Islamophobia. It also places suspicion on the wider Australian Muslim community.

Moorhouse calls for a new compact between ASIO and Australian society. In doing so, he explores issues of privacy, freedom of expression, censorship and what he terms “civic dignity”. It is at once respectful of ASIO’s successes and critical of its transgressions. He describes ASIO as:

… sometimes getting it wrong with potentially disastrous effects, and sometimes saving Australian lives.

Australians Under Surveillance deserves to be widely read, and its ideas carefully considered.

Lachlan Clohesy, Lecturer in History, College of Arts, Victoria University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

|

Tree of Life

by Ranjit Lal (Ranjit Lal is an author and environmentalist), The ultimate feel-good experience, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate | Peter Wohlleben | Introduced by Pradip Krishen | Allen Lane | 317 Pages | Rs 699

WE TEND TO take trees for granted, because, well they’re always stuck in the same place for all our lives—and much longer—unless of course we chop them down or they fall over in a storm or die (slowly) of some unseen cause. And most of the time they don’t seem to be doing anything, except standing there waving their leaves and branches in the breeze. For a generation that’s addicted to instant gratification, they may seem, dare one say, boring.

Ah, but that’s only because trees are slow and deep and only now—thanks to the persistent study and observations by people like Peter Wohlleben—are revealing their incredibly complex and almost sentient secret lives. Wohlleben spent his career in the forests of his native Germany, basically assessing trees for their timber potential, and he gradually got an idea of what trees have been hiding from us all this time. Indian readers might wonder how relevant his discoveries are because he writes mainly of the trees found in the old growth and plantation forests of his native Germany and Central Europe: oaks, beeches, birches, spruce, firs, pine and so on, which have a relatively limited range in India—confined mainly to mountainous regions. But I guess, what’s good for the oak is good for the neem and peepul too, and at any rate, this book can serve as a template towards the better understanding of our ‘native’ species.

Another thing that might put some readers off is that (as Pradip Krishen mentions in his ‘Introduction’) the book’s name is unfortunately similar to that of Peter Tompkins’ The Secret Live of Plants (1973), which raised many botanical eyebrows. But thankfully this book is much more grounded in hard science and less so in sentimentality. Wohlleben writes with affection and wonder, not with cloying sweetness.

There’s an astonishing amount of fascinating information packed into this book. At first glance, much of it seems incredible and exaggerated and even rather anthropomorphic (botanically speaking), but when the explanations are provided, appear to be so rational that you wonder, ‘Why the heck didn’t I think of this before?’ Trees communicate with each other, even share nutrients with each other, warn each other of danger; grand matriarchal trees look after their babies, trees learn from bitter experience, they avoid incest, some migrate, some (in cities and parks) grow up like ‘street kids’ and many may live for 500 years or more.

One of the most amazing recent discoveries was that of the vast, underground symbiotic fungal (mycorrhizae) system that connects the roots of trees, enabling them to exchange nutrients and issue warnings to one another when they comes under attack; it’s been called the ‘wood wide web’ and like the other one, is hugely extensive. Trees that are not doing well or are nutrient-deficient are ‘helped’ by others through this network. These fungal hairs actually burrow into the roots—and oh yes, they tax the trees at a rate of as much as 30 per cent, taking carbohydrates and sugar from the tree in return for their services. Not all fungi are friendly, though; some are the biggest enemies of trees, just waiting for a breach in the tree’s defences (a tear in the bark) to enter, so they can begin rotting it from inside out.

Another fact that widened my eyes was the assertion that deep shade and slow growth were indeed very good for baby trees—those which grow under their mother’s canopy. Only about 3 per cent of sunlight percolates down to the forest floor, and in this dim light baby trees are hard-pressed to grow fast (as perhaps they would like, being teenagers and all). But what seems ‘bad’ for you (like all bitter medicine) is actually good for you. In slow-growing trees, the trunk grows tightly, highly compacted and strong, with little air-spaces between the cells; in fast-growing trees, there are larger air spaces which makes fungal attacks easier. It’s only when the mother tree dies and falls that the youngsters can revel in the sun and shoot up, and by this time they’re hardy young buggers (maybe already 100 years old) ready to take on anything. Fast growers topple easily.

In some forests, the trees virtually ‘conspire’ together to survive. Beeches and oaks for instance, might remain seedless some years, causing the population of browsers—deer and their ilk—to crash. The next year they lay out a bumper crop, too much for the surviving animals to consume and thus leaving many beechnuts and acorns strewn around, ready to sprout. If there had been a baby boom of deer that year, the animals would have cleaned up and there would be no next-gen of oaks and beeches.

Trees learn from experience: Wohlleben writes that a tree hitherto used to a plentiful supply of water and extravagant in its use, would suffer considerably in a drought year. If it were to survive this, it would remember the harsh experience and in future, behave in a far more frugal manner, ensuring there is a reserve stored beneath its roots, just in case—something we profligates could perhaps learn from. Something else we (especially the mandarins in power who are hell-bent on felling everything in sight) would be sensible to remember is how vital forests are for rainfall in the interiors. Moist air hitting the coastal forests condenses and falls as rain here; some evaporation is returned through transpiration by the trees and is blown further inland where the process is repeated, the rains thus being drawn further inland to areas which otherwise would have received no rain.

As for trees in city parks and avenues, Wohlleben calls them the ‘street kid’ equivalent of trees: Not only are their roots shallow, but are not allowed to spread because of obstructions such as pipes, cables and building foundations. Then there’s traffic pollution the leaves have to breathe day in and day out, and the hard tarmac and concrete do not cool down at night like a forest floor does. Park trees are, of course, ‘spoiled’ by us initially, given lots of water, fertilisers and TLC, and grow like ‘doped up bodybuilders’— short and squat, with low crowns, standing on highly compacted ground which does not allow water to percolate and are very unsteady on their pins. Then one day, the care and lavish watering stops and the trees aren’t geared to handle life on their own. (Sounds familiar?)

Another puzzling question that Wohlleben tackles: why are trees so long-lived and how does it help in their evolution? A quick turnover of generations means there are better chances of genetic tweaks and modifications to ensure survival of a species: those most suited to the environment survive. Bacteria and viruses, as we all know, mutate with changing circumstances, often to get the better of antibiotics and vaccines. Trees may be 100 years old before they have their babies and pass on genes. The secret of their success is simply that each individual tree is almost as genetically different from another of the same kind as to almost be a species in its own right. Thus, in a forest, some trees (all of the same species) may be better equipped to handle the cold, others to deal with heat, still others do okay when there’s drought; basically there are some trees around that will survive whatever contingency or emergency that may occur, thus ensuring the survival of the species.

And, oh yes, trees do avoid ‘incest’. Trees which have both male and female flowers open these out at different times, others use the wind to blow their pollen away, and if the worst does happen: a tree pollinates itself, it genetically recognises what’s going on and stops any further nonsense by sealing the tubes down which the pollen descends, ensuring no fertilisation can take place.

Apart from the treasure trove of information it provides, what’s the biggest takeaway from this book? Maybe it’s a reminder that we should slow down the frenetic pace of our lives, which makes us skim superficially over anything worth a deeper look, and which gives us hypertension, road rage et al. Trees are barely out of their childhood when they are 100 years old—and know how to deal with our rocketing BP too. Take a walk in an undisturbed forest and breathe deeply, and you’ll be lifted with the ‘feel-good’ factor that the trees spread around—your BP will be back to normal.

But yes, thanks to what we call ‘development’ it may be virtually impossible to find that pristine, untouched forest first.

Ranjit Lal is an author and environmentalist Source: OPEN Magazine

|

Along the White Clouds

By Mohit Satyanand, The eternity of Himalayan pursuits: Himalaya Adventures Meditation Life | An anthology edited by Ruskin Bond and Namita Gokhale | Speaking Tiger | 444 Pages | Rs 799

‘WE NEVER GROW tired of each other, the mountain and I.’ I speak not for the mountain, as Chinese poet Li T’ai Po did, but Jawaharlal Nehru’s response so echoes mine: ‘I cannot say that I never grew weary, even of the mountain; but that was a rare experience, and, as a rule, I found great comfort in its proximity. Its imperturbability mocked at my varying humours and soothed my fevered mind.’

I can count the decades of my life on a rosary of the Himalayas—childhood summers on the Dal lake and in Gulmarg; a family pilgrimage to Kedarnath, which shaped my views on ritual and religion; my first adult trek; a treacherous expedition from Spiti to Ladakh; the heady romance of early marriage in our stone cottage in Kumaon; safari-style treks, with shower stalls and espresso coffee, when my love affair with remote valleys accommodated middle-aged definitions of comfort; and this summer’s walk with my son to the base camp of his first Himalayan summit.

My imagining of my life was shaped by an ever-expanding library of Himalayan writing—by Peter Matthiessen and Andrew Harvey; by Paul Brunton and Jim Corbett; by Lama Anagarika Govinda, and Heinrich Harrer, all represented in this delectable anthology. Each devotee of the Himalaya must find his path between the bookends of adventure and contemplation, so wonderfully phrased by Brunton: ‘In a multitude of places upon this sorry planet, a multitude of men are running hither and thither or jumping this way and that, in an endeavour to develop a more athletic body by such constant activities. I, on the contrary, am pinning this body down to a dead stop, in an endeavour to free myself from all intimations of physical sensation.’

Everest, inevitably, is the flagship of the ‘Adventure’ section, with familiar writing by George Mallory and by Edmund Hillary, who refused to tell the world who stepped on Everest’s summit first— he, or Tenzing Norgay; 43 years later, Norgay’s son, Jamling, summited Everest, and his lucid writing is as much a celebration of climbing as a history of climbing between his father’s time and his.

Then, attempting Everest in 1953, ‘my father was fully mindful that at that time, eighteen had died, and none had made it.’ Now, ‘I have taken dubious solace myself in the thought that, for every person who has died on Everest, five have made the summit.’

Ironically, that climbing season, 1996, was one of the most disastrous on Everest. Jon Krakauer, not represented here, tells the story of that fateful long day and night in one of the most successful pieces of mountain writing, Into Thin Air, a tragic tale of commercialisation, expediency, and bad decision-making.

An eccentric counterpoint is the misadventure of the occultist Aleister Crowley, who cobbled together a motley crew in the first-ever attempt on Kangchenjunga. His ‘coolies’ possessed ‘no notion of self-respect, no loyalty, no honesty and no courage.’ Of his team doctor, he wrote, ‘I should have broken his leg with an axe, but I was too young to take such a responsibility.’ To supervise bandobast, he recruited the manager of a Darjeeling hotel, an Italian named Righi, whose character ‘was mean and suspicious and his sense of inferiority to white men manifested itself as a mixture of servility and insolence to them, and of swaggering and bullying to the natives’. And to remove any doubts about his political correctness, Crowley wrote that women ‘are nothing but children grown up.’

Another Himalayan adventure is recounted by Mark Twain, who journeyed 35 miles of rail track down from Darjeeling in a pilot car that hugged the ground and swooped down the hill. In his telling, it sounds like the longest roller coaster ride on earth, beginning with ‘a gaspy shock that took my breath away... it was a sudden and immense exaltation, a mixed ecstasy of deadly fright and unimaginable joy’. A few miles down the mountain, Twain’s party stopped to view a Tibetan drama performance, which he describes in the finest Orientalist tradition of his time: ‘as a drama, this ancient historical work was defective, I thought, but as a wild and barbarous spectacle, the representation was beyond reproach’.

Remote Himalayan regions always inspired the search for the exotic. German-born Lama Anagarika Govinda’s The Way of White Clouds is one of the classics, and the passage I remember most acutely reads, ‘unwittingly and under the stress of circumstance and acute danger I had become a lung-gompa, a trance walker, who, oblivious of all obstacles and fatigue, moves on towards his contemplated aim, hardly touching the ground, which might give a distant observer the impression that the lung-gompa was borne by the air (lung), merely skimming the surface of the earth.’ The present Himalaya anthology has a metaphysical piece from the Lama’s book, on the ‘Nature of the Highlands’; a deep encounter with mysticism is provided by a contemporary piece, ‘Shamans in Nepal’. Wolfgang Büscher describes his recovery from deep exhaustion aided by the presence of a shaman. Without comment, he offers the explanation of his porters, ‘You saw Shiva—he was the black figure. You were afraid to see him uncovered, and at the same time, you wanted to. That is how it is with men and gods. We want to be close to them, and yet we are afraid of them, and rightly so.’

THERE’S ‘ADVENTURE’, ‘Meditation’, and finally ‘Life’, the third section of the book, which rightly features many more writers from our Subcontinent than the earlier segments. But none from Pakistan. Except for a fleeting mention in Amitava Ghosh’s reportage on the Siachen glacier, it’s as if the Himalayas abruptly ended at our western Line of Control. Whether it’s Mount K2, or the Hunza valley, our neighbour has iconic Himalayan regions, and their omission from this anthology is striking.

My favourite piece in this section evocatively links the life of sherpas with the threat of death. Sixty years of mountaineering stories have glamourised her tribe, of which Jemima Sherpa writes, ‘Everyone loves us, everyone trusts us, and everyone wants their own collectable one of us. Internet listicles call us badass.’ Inevitably, though, the news carries ‘the body counts, four, no six, no ten.’ The following year, when families meet in the Khumbu, ‘in each line, there will be gaps, like missing teeth.’ And the young will have to shuffle forward, ‘a little closer to the fire to fill the spaces of the ones that are missing.’

Death comes suddenly in the mountains, and two recent disasters remind us of the scale of Himalayan disaster. Writing of the 2015 Nepal earthquake, Rabi Thapa quotes a hydropower researcher, Austin Lord ‘I looked up the valley where you could see Langtang village, and there was just a wall of snow. It was insane. I was standing there with Dhindu, and everyone was saying ‘sabai gayo’, which means, it’s all gone.’

Two years earlier, I was transfixed by the horror of my television screen relaying images of riverine wrath from Kedarnath. Hridayesh Joshi’s writing is bland in the translation, but this quote from a temple priest is telling: “It was as though Yamraj was actually in our midst.... Within minutes, Kedarnath was filled with water, and dotted with large boulders… To save myself, I had to jump into the swirling waters below and was swept away… miraculously, the water deposited me on the side, and I lay there, for a long time.”

Nevertheless, we will return, we hopeless devotees of the Himalaya. I will borrow Dharamvir Bharti’s words to write my love letter, ‘I will return. I will return, again and again and again. Your heights are my home, where my heart finds peace... I am helpless in this.’Source: http://www.openthemagazine.com

|

Goa’s first Konkani book on birds

SACHI NAIK: “There is a saying in Konkani – ‘Mor nachta mhunun kutture nachta’. Until now I had not known what Kutture meant. During my research for the book I found out that Kutture is a Red Spurfowl,” says Konkani writer Harsha Shetye who brought out a research book, ‘Goenchi Sukni’ in collaboration with photographer Vedang Sawant, published by the Goa Forest Department that will be released on November 11 at the inaugural of three-day Bird Festival of Goa at Bondla.

Harsha Shetye has earlier written travelogues, short stories and poems in Konkani, however, ‘Goenchi Sukani’ is first Konkani book on birds. “This is the first time someone has documented the Konkani names of birds found in Goa,” she says.

Harsha has always been passionate about bird watching. “In my childhood, I spent my holidays at Sanquelim. In the evening my grandfather would take us up the hills and point out at birds, naming them. My cousins have forgotten the names, but I remembered a few. Around seven years ago when I shifted to my new house, I found many uncommon birds around. This intrigued me and I began reading Salim Ali’s books or searching the internet to identify these birds.”

Harsha has been researching the original Konkani words for varied thing like old Goan furniture and utensils as a hobby. “I like researching Konkani names of anything I come across, so I mixed my passion of bird watching and Konkani names and eventually got out this research book.”

She credits Facebook for the idea of a research book on birds. She says, “A Facebook group called Konkani Speaks is to be credited. Photographer, Vedang Sawant would post photos of Goan birds and caption each with ‘guess the bird’. Since I would always guess it right, he suggested that I put my knowledge of Konkani bird names into a book. He said that he has a lot of photos of birds that could go into the book,” she says.

Prior to this book, Harsha has written several articles on birds for Konkani magazines like ‘Jaag’ and ‘Bimb’. Each page of ‘Goenchi Sukni’ includes a picture with the Konkani, Marathi, English and Scientific names of the bird, along with a short description; Harsha has also added Goan folklore associated with that particular bird. There are 432 birds in Goa though she has only found the names of around 182 birds till date. “I have just found 25 per cent of names of local birds. Mostly, I found these birds in Sanguem, Canacona, Sattari and a few in Bardez,” says Harsha.

She says that several Konkani folklore mentions the names of local birds that have faded into oblivion and these find their way into the book. “There were several folklores that I heard or learnt in my childhood; many are based on birds, their sound and their appearance, and I have included them in my book,” says Harsha.

She says that it was difficult to compile the names of the birds, taking her about five years to complete her compilation: “During my research, I would find the Marathi, English and Scientific names of the birds in the written word, but people helped me to find the Konkani names. However, the same bird is sometimes called by different names by different communities. This was the most difficult part.”

The book that has more than 130 photographs by Vedang, also has pictures by Deepa Kamat, Arabinda Pal, Vivek Naik, Justinho Rebelo, Omkar Naik and Sudhir Inamdar. About the dwindling bird population, Harsha says: “It is sad that people cut trees. We fail to understand that trees are a basic need for birds. It is their food as well as their home.”

This book is just a start, says Harsha. “Further, I want to find Konkani names of all the local birds of Goa. I have been collecting the names of old utensils and furniture too. I want to do something about that too. But for now, birds are my priority,” says Harsha with a smile. Source: http://www.navhindtimes.in/

|

Reading When Writing With: Gunjan Jain

By Dhvani Solani: The relationship between reading and writing is an old, torrid one, both leaving an indelible imprint on the other. In this column, we seek to answer a question we’ve often asked ourselves – what did the author have on their bookshelves while penning their latest work. This month, we throw the question to Gunjan Jain whose book – She Walks, She Leads (Penguin Random House) – is an anthology of 24 women achievers at the pinnacle of their profession, from Indra Nooyi and Chanda Kochhar to Mary Kom and Priyanka Chopra.

What: “I read fewer books during the writing of this book as my efforts were to read books penned on similar concepts for inspiration. I also did not want existing books to taint my creativity. But largely, I read tons of material related to the people in the book.”

Why: “When I’m writing, what I read is primarily for information, or to see if there are other facets that I need to look at. However, I can’t deny that subconsciously I may have been influenced somewhat by what I read. Usually I concentrate on authors and books that have to do with what I’m writing, but sometimes when I get stuck I read light fiction to take a break and recharge my batteries. It usually works, and I can get back to what I’m doing with a fresh mind.”Source: Grazia India

|