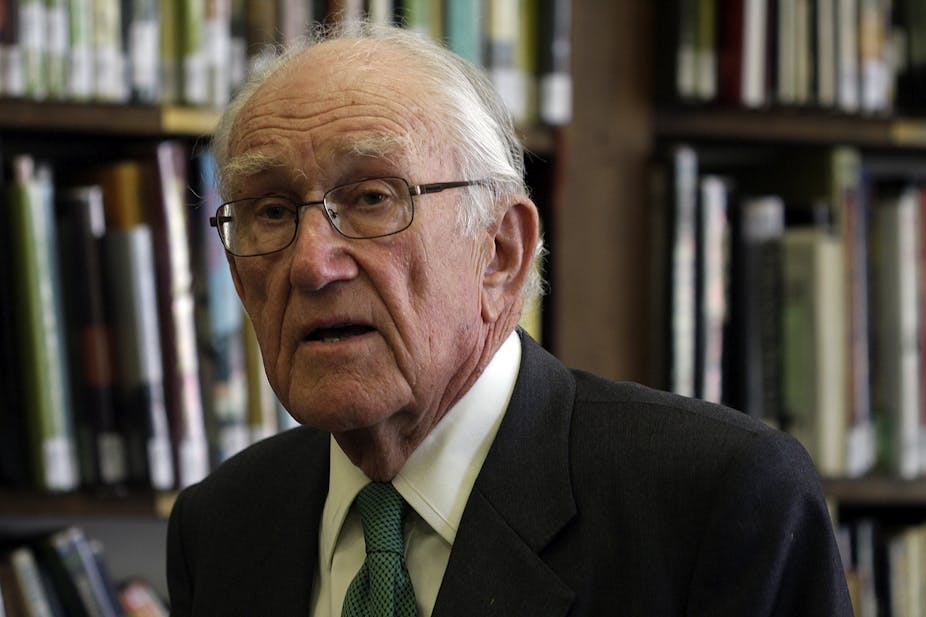

Mark Beeson, Murdoch University: Malcolm Fraser occupies a rather unique place in Australia as someone who has, at different times, managed to incense both ends of the political spectrum. If nothing else this is indicative of someone who has a capacity to change his position over the course of a lifetime. Fraser’s new book, Dangerous Allies, seems certain to cement his place as an unexpected, late-blooming radical.

The content of Dangerous Allies will be familiar to anyone who has taken an interest in Fraser’s recent career as a polemicist and public intellectual. The principal focus of this book is Australia’s relationship with the United States, and what Fraser describes as the associated dangers of “strategic dependence”.

Simply put, this is a consequence of the belief that Australia’s security is best guaranteed by the cultivation of what former prime minister Robert Menzies famously described as “great and powerful friends”.

Fraser’s argument is that while strategic dependence may have been understandable and defensible during the early years of Australia’s post-colonial history and the Cold War, it is now a liability, and a potentially dangerous one at that. Whatever one thinks of Fraser’s arguments in favour of this position, the chapters devoted to these periods are impressively scholarly and – especially in the more recent periods – enlivened with anecdotes of the when-I-spoke-to the-president variety.

One of the reasons this book is likely to upset so many on the conservative side of politics is not simply because Fraser adopts such an iconoclastic attitude toward the centrepiece of Australian security policy for more than half a century, but because he’s scathing about the some of the icons of the Liberal Party, too.

Menzies suffered from a “great misunderstanding” about the importance of Britain, Fraser contends, while Howard further entrenched the culture of strategic dependence on the US to the detriment of our regional relations.

By contrast, Fraser gives some Labor luminaries such as Gough Whitlam and especially Doc Evatt great credit for attempting to carve out a more independent foreign policy. The current generation of Labor leaders, however, suffer from the same “bipartisan failure” that has circumscribed our capacity to make separate strategic decisions from the US. The net result, Fraser argues, is that:

We have significantly diminished our capacity to act as a separate sovereign nation.

No doubt the present government – and opposition, for that matter – will dismiss such claims out of hand. So too will the great majority of strategists in Canberra, be they military or civilian. But Fraser is surely right to question the supposed benefits that have accrued to Australia from participation in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Significantly, Fraser is more equivocal about Vietnam (where he had ministerial responsibility), although much the same could have been said about that conflict too.

Although Fraser judges that America’s involvement in Vietnam was an “unmitigated failure”, he also concedes that it was a commitment he “fully supported”. His justification for what he now sees as a misjudgement was that the US was either “derelict in their duty to inform us of the true situation” or “deceitful”. He is even more scathing about America’s preparedness to “murder” former political allies when it suited them.

What faith can a nation have in an ally that believes it is within its right to remove the nation’s head of state?

It’s a good question, and one that might have been addressed to Australia’s own constitutional coup and the rumours that persisted about CIA involvement in Whitlam’s downfall. Of this possibility, however, there is notably no mention. Being in the thick of it, so to speak, is something else that exercises a constraining effect.

If there is one thing that this book serves to demonstrate it is just how difficult exercising independent thought and action actually seems to be when in office – particularly as far as relations with the US are concerned. Although Fraser now admires New Zealand’s “far-sighted and correct” independent foreign policy, while inside the Canberra bubble he dutifully joined the chorus of condemnation.

While I am sympathetic to many of the arguments Fraser develops, I have no expectation that they will have the slightest impact in Canberra. I have been making a similar argument about the possible benefits of a more independent, less-aligned foreign policy for more than a decade now, with absolutely no discernible impact on the policy debate, much less on policy itself.

True, I’m not a former prime minister. Fraser’s book will at least be extensively reviewed and discussed. Whether it will it make any difference is another question.

It is possible to quibble with a number of aspects of the book, even if one is not overtly hostile to its core idea. Fraser’s faith in the diplomatic capacities of the ASEAN states, especially as far as China is concerned, looked overly optimistic even before the latter’s more aggressive pursuit of its territorial claims.

Similarly, Fraser’s suggestion that defence spending is likely to rise as the price of independence is both debatable and unlikely to win converts to the cause. New Zealand might still have lessons to offer in this context.

Nevertheless, this is one of the most original and timely contributions to a debate that, with a few honourable exceptions, tends to be sterile, predictable and unchanged since the end of World War Two.

As Fraser points out, the world has changed profoundly in the interim. It’s about time some of our thinking began to reflect the new realities, too, he suggests. An independent Australia could actually play a useful role in doing precisely that.

|