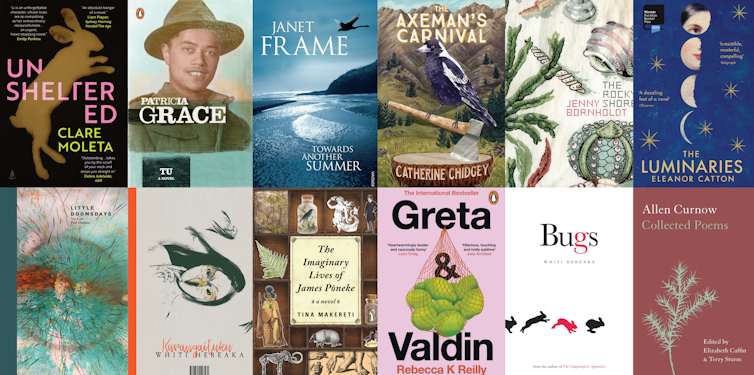

Finlay Macdonald, The Conversation; Jo Case, The Conversation; Matt Garrow, The Conversation, and Suzy Freeman-Greene, The Conversation Finlay Macdonald, The Conversation; Jo Case, The Conversation; Matt Garrow, The Conversation, and Suzy Freeman-Greene, The ConversationLast month, we enjoyed reading The New York Times Best Books of the 21st century – but were disappointed it included no Australian or New Zealand authors. From New Zealand, even Booker winner Eleanor Catton and Women’s Prize longlisted Catherine Chidgey, writers whose books have made a significant impact in the US and UK, didn’t get a mention. So, the Conversation’s Books & Ideas team decided to create our own Australian and New Zealand lists. For Aotearoa New Zealand, we worked with The Conversation’s NZ editor Finlay Macdonald, a former book publisher and Listener editor. Together, we asked more than 20 local literary experts to each share their favourite NZ book of the century. The result was a list of 20 top books, including titles by Catton and Chidgey, together with a rich treasure trove of honourable mentions (we allowed up to two each). The three books that tied as the most picked were Jenny Bornholdt’s The Rocky Shore (2008), Chidgey’s The Axeman’s Carnival (2022) and Tina Makereti’s The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke (2018). And what were our own picks? Finlay’s top spot goes to Lloyd Jones’ The Book of Fame (2000), for turning rugby into art, with his honourable mention going to Michael King’s Penguin History of New Zealand (2003), for making local history a massive bestseller. Books & Ideas editor Suzy Freeman-Greene and deputy editor Jo Case both chose Chidgey’s 1980s-set psychological thriller Pet (2002) as their very favourite, for its biting social observations and escalating menace. Jo’s honourable mentions are Catton’s The Rehearsal (2008) and Emily Perkins’ Novel About my Wife (2008), while Suzy’s are Catton’s The Luminaries (2013) and Perkins’ Lioness (2023). If you’d like to play this game too, scroll to the end of the article to leave a comment. We’ll share selected results in our Books & Ideas newsletter next Friday. (You can subscribe here if you don’t get it already.)

Finlay Macdonald, New Zealand Editor, The Conversation; Jo Case, Deputy Books + Ideas Editor, The Conversation; Matt Garrow, Editorial Web Developer, The Conversation, and Suzy Freeman-Greene, Books + Ideas Editor, The Conversation This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

20 best New Zealand books of the 21st century: as chosen by experts

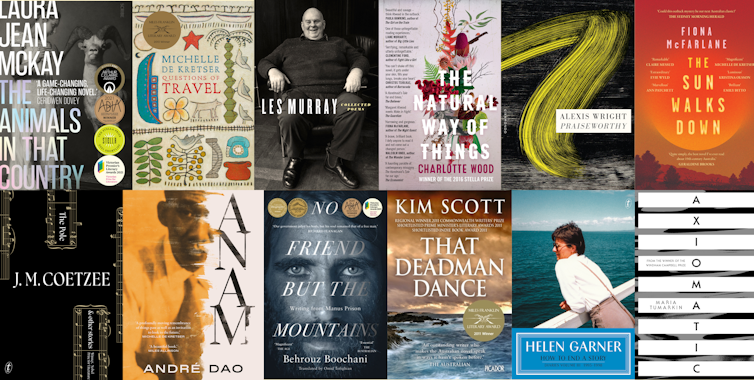

Best Australian books of the 21st century: as chosen by 50 experts

Like so many avid readers around the world, I was fascinated by the recent New York Times list of the Best Books of the 21st century, as voted by 503 authors, critics and book lovers. But like many Australians, I was disappointed to see no Australian books on the list. Even those authors who’ve made a splash in the US literary scene this century – Helen Garner, Gerald Murnane, Maria Tumarkin – didn’t get a guernsey. That’s where we come in. The Conversation’s Books & Ideas team, seeking to right a wrong (and just very curious), asked 50 Australian literary experts to each share their favourite Australian books of this century. I’m pleased to say the aforementioned authors are all represented here – along with a host of others, ranging from household names and local literary darlings to excellent (we’re told) books and authors you might not have heard of until now. We were unsurprised to see Waanyi author Alexis Wright, who made history by winning both the Miles Franklin and the Stella Prize for her epic Praiseworthy, topping our most-picked list. Melbourne bookseller Readings recently asked members of the Australian literary community to nominate their best Australian books of the 21st century, creating a ranked top 30. Our approach is a little different: we’ve included all 50 nominations, with a few words from our experts – and we’ve allowed two honourable mentions each. What are our personal picks? Books & Ideas editor Suzy Freeman-Greene’s number one book is Extinctions by Josephine Wilson. Her honourable mentions are Burial Rites by Hannah Kent and Joe Cinque’s Consolation by Helen Garner. Fellow deputy editor James Ley, our resident 2024 Miles Franklin judge (doesn’t every books section have one of those?), chose Brian Castro’s Shanghai Dancing, closely followed by Wright’s Carpentaria (narrowly edging out Praiseworthy, if only because it came first) and J.M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello. And me? My very favourite is Tumarkin’s deeply ethics-driven work of creative nonfiction, Axiomatic. My honourable mentions are Dark Palace by Frank Moorhouse and How to End a Story: Diaries 1995–1998 by Helen Garner. If you’d like to play this game too, scroll to the end of the article to vote in our poll or leave a comment. We’ll share selected results in our next Books & Ideas newsletter. (You can subscribe here if you don’t get it already.) And look out for New Zealand’s Best Books, which we’ll publish soon. Jo Case, Deputy editor, Books & Ideas, The Conversation This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Book reviewing is an art, in its own way

All serious writers should take their own work, and the efforts of others, seriously. photosteve101 Suzie Gibson, Charles Sturt University There should be no hard and fast rules concerning book reviewing. That’s because reviewing constitutes a worthy genre in its own right, one that should not be limited by guidelines or mandates. Criticism is a very important art. It is also a mark of our democracy. It should therefore enjoy the same freedom as other aesthetic forms such as poems, novels, plays, essays and so forth. The opening line of John Dale’s article on book reviewing on The Conversation – “Good book reviews are all alike while every bad review is bad in its own way” – at first seemed overly flippant to me. But giving the line more thought, it is perhaps useful to make something good out of it. The quip echoes Tolstoy’s famous opening line in Anna Karenina: All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. The phrase in its own way is an important fragment to hold onto in these two disparate sentences: those four words are crucial to preserving the liberty of criticism, and in this case, the book review form. To exist as an independent entity – that is, as a definitive aesthetic form – book reviews must offer both aspiring and experienced writers the opportunity to be persuasive, ironic, intelligent, witty and critical. That is one good reason reviewers deserve to be given an identity, which is also about bequeathing them a humanity. Jane Messer’s intelligent piece for The Conversation on The Saturday Paper’s omission of critic’s names in the book review section provides an important perspective on the responsibilities of reviewing. All serious writers should take their own work, and the efforts of others, seriously. That is why they should own their work. Putting a name to their writing is about taking responsibility for their judgements, which should be well argued and convincing. There is an unwritten ethical code between the writer and her or his work. It is surprising as well as disappointing that The Saturday Paper identifies its reviewers only through initials. This has the effect of undercutting the value of the genre of reviewing, indeed of the art of writing itself. The kind of aesthetic beauty forged out of good critical writing is something that needs to be fostered and protected since it is about enabling an inquisitive and lively literary culture to emerge and to flourish. The reader is key to advancing this ambition. Dale is right to point out that the reader matters in a book review. But the reader is, as Peter Rose rightly pointed out in his reply to Dale on The Conversation, never a knowable or tangible phenomenon. Moreover, there are never ideal readers, just as there are no perfect authors. We are all flawed beings. That is not something to mourn but to relish in. Good writing is often created out of struggle, doubt and feelings of ineptitude. The emphasis on readers is an important aspect to writing – all kinds of writing. But what must not be forgotten is the importance of the text itself. That is, the kind of writing that lives and resonates in its own way. In its own way can be taken as a leitmotif which reinforces the importance of writerly freedom. Yet what also needs to be acknowledged is that many great writers are insightful critics. Take for instance the late 19th-century luminary, Henry James (1843-1916) who wrote novels such as The Portrait of A Lady (1881) and The Turn of the Screw (1898) while also critiquing the merits and shortcomings of his predecessors and peers, such as the extraordinary George Eliot (1819-1880) and remarkable Èmile Zola (1840-1902). Literary criticism may not always be kind yet its dissent can be so very invigorating as well as inspiring. James famously criticised Tolstoy’s novels for being “large loose baggy monsters”. What an imaginative way to chastise one of the world’s greatest writers! James always believed in the importance of literary criticism and he championed the power of good writing. He even went so far as to carefully critique his own fictions, as his famous “Prefaces” to the New York editions of his novels testify. Good writing, whether it be a book review, an essay or a blog, needs to be encouraged, not disparaged in our developing literary culture. Writers need to be identified, as this is surely always encouragement to strive for excellence regardless of the pay cheque or lack thereof. The calibre of our cultural debates and conversations depend upon the hard work of writers, critics and editors who grapple everyday with the genuine difficulties of writing well and thinking clearly. The power and importance of words, ideas and books cannot be understated. England knew that its empire was wedded to the influence of its literature which is why it still reigns as a dominant literary culture. The US took note of England’s monopoly in carving out a literature of its own. And now through its film and TV it is the most persuasive narrative culture today. Australia should remain cognisant of the importance of writers in developing its own narrative and cultural identity. The significance of literary criticism, and in particular the book review form, plays a key role in this process. The conversation between readers, writers, authors and critics needs to be an open and genuine one, giving us the chance to become the curious and intelligent nation that we aspire to be. Good writing and intelligent criticism not only makes this ambition possible – it enables it to become a reality. Suzie Gibson, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, Charles Sturt University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. All serious writers should take their own work, and the efforts of others, seriously. photosteve101 Suzie Gibson, Charles Sturt University There should be no hard and fast rules concerning book reviewing. That’s because reviewing constitutes a worthy genre in its own right, one that should not be limited by guidelines or mandates. Criticism is a very important art. It is also a mark of our democracy. It should therefore enjoy the same freedom as other aesthetic forms such as poems, novels, plays, essays and so forth. The opening line of John Dale’s article on book reviewing on The Conversation – “Good book reviews are all alike while every bad review is bad in its own way” – at first seemed overly flippant to me. But giving the line more thought, it is perhaps useful to make something good out of it. The quip echoes Tolstoy’s famous opening line in Anna Karenina: All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. The phrase in its own way is an important fragment to hold onto in these two disparate sentences: those four words are crucial to preserving the liberty of criticism, and in this case, the book review form. To exist as an independent entity – that is, as a definitive aesthetic form – book reviews must offer both aspiring and experienced writers the opportunity to be persuasive, ironic, intelligent, witty and critical. That is one good reason reviewers deserve to be given an identity, which is also about bequeathing them a humanity. Jane Messer’s intelligent piece for The Conversation on The Saturday Paper’s omission of critic’s names in the book review section provides an important perspective on the responsibilities of reviewing. All serious writers should take their own work, and the efforts of others, seriously. That is why they should own their work. Putting a name to their writing is about taking responsibility for their judgements, which should be well argued and convincing. There is an unwritten ethical code between the writer and her or his work. It is surprising as well as disappointing that The Saturday Paper identifies its reviewers only through initials. This has the effect of undercutting the value of the genre of reviewing, indeed of the art of writing itself. The kind of aesthetic beauty forged out of good critical writing is something that needs to be fostered and protected since it is about enabling an inquisitive and lively literary culture to emerge and to flourish. The reader is key to advancing this ambition. Dale is right to point out that the reader matters in a book review. But the reader is, as Peter Rose rightly pointed out in his reply to Dale on The Conversation, never a knowable or tangible phenomenon. Moreover, there are never ideal readers, just as there are no perfect authors. We are all flawed beings. That is not something to mourn but to relish in. Good writing is often created out of struggle, doubt and feelings of ineptitude. The emphasis on readers is an important aspect to writing – all kinds of writing. But what must not be forgotten is the importance of the text itself. That is, the kind of writing that lives and resonates in its own way. In its own way can be taken as a leitmotif which reinforces the importance of writerly freedom. Yet what also needs to be acknowledged is that many great writers are insightful critics. Take for instance the late 19th-century luminary, Henry James (1843-1916) who wrote novels such as The Portrait of A Lady (1881) and The Turn of the Screw (1898) while also critiquing the merits and shortcomings of his predecessors and peers, such as the extraordinary George Eliot (1819-1880) and remarkable Èmile Zola (1840-1902). Literary criticism may not always be kind yet its dissent can be so very invigorating as well as inspiring. James famously criticised Tolstoy’s novels for being “large loose baggy monsters”. What an imaginative way to chastise one of the world’s greatest writers! James always believed in the importance of literary criticism and he championed the power of good writing. He even went so far as to carefully critique his own fictions, as his famous “Prefaces” to the New York editions of his novels testify. Good writing, whether it be a book review, an essay or a blog, needs to be encouraged, not disparaged in our developing literary culture. Writers need to be identified, as this is surely always encouragement to strive for excellence regardless of the pay cheque or lack thereof. The calibre of our cultural debates and conversations depend upon the hard work of writers, critics and editors who grapple everyday with the genuine difficulties of writing well and thinking clearly. The power and importance of words, ideas and books cannot be understated. England knew that its empire was wedded to the influence of its literature which is why it still reigns as a dominant literary culture. The US took note of England’s monopoly in carving out a literature of its own. And now through its film and TV it is the most persuasive narrative culture today. Australia should remain cognisant of the importance of writers in developing its own narrative and cultural identity. The significance of literary criticism, and in particular the book review form, plays a key role in this process. The conversation between readers, writers, authors and critics needs to be an open and genuine one, giving us the chance to become the curious and intelligent nation that we aspire to be. Good writing and intelligent criticism not only makes this ambition possible – it enables it to become a reality. Suzie Gibson, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, Charles Sturt University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

'Vast Canyon of Books' New Public Library in China

'Vast Canyon of Books' Splits Open in Stunning New Public Library in China, Wuhan Library © MVRDV Architects 'Vast Canyon of Books' Splits Open in Stunning New Public Library in China, Wuhan Library © MVRDV ArchitectsPoised to become one of the largest libraries in China, the new Wuhan Central Library takes inspiration from its geographical positioning at the confluence of two rivers. Just as the waters at the confluence of the Yangtze and Han rivers are pulled into a central channel, visitors are swept into the library as if into a monumental canyon, with sedimentary layers replaced by shelves of books. The 140,000-square-meter project connects to its surroundings via three large openings that will act as visual displays of life inside the building, sparking curiosity and intrigue. This distinctive, three-faced flowing shape celebrates the position of the “city of 100 lakes” at the confluence of two rivers, and will become a new recognisable landmark for Wuhan. Managed by Dutch architects MVRDV, the library celebrates the sculptural force of rivers, and is set to be the focus of a “city versus nature” exterior scene, with tall vertical windows looking out over Wuhan’s central business district, and a long horizontal windowed wall looking out on a large park coming as part of the project. “The topography of Wuhan was an important source of inspiration: we have this idea of a horizontal view towards the lakes and on the other hand, we have this more vertical view towards the city with the high rises,” says Jacob van Rijs, founding partner of MVRDV on their website. “This is nature versus the city, and the building is somehow focusing on this. I think this makes it an exciting place to gather.”   Wuhan Library © MVRDV Architects Wuhan Library © MVRDV ArchitectsLarge native trees will shade exposed areas of the interior from Wuhan’s hot climate. The advantage of using native vegetation is that little maintenance is needed to support their growth. Sets of angled slats fixed at regular intervals called “louvres” will coat the roof of the building to reduce heat absorption.“Openable elements for natural ventilation, combined with the use of smart devices and an efficient lighting system further reduce the building’s energy demands, while solar panels incorporated into the library’s flowing roof shapes provide the building with renewable energy,” the architects’ website explains. 'Vast Canyon of Books' Splits Open in Stunning New Public Library in China

|

At a time of crisis, reading books can help us make sense of the world

Beth Driscoll, The University of Melbourne Why do any of us read books these days? There are so many other forms of information and entertainment that are much easier to consume. With 20 minutes to hand, why wouldn’t you just scroll for a while through TikTok, or check in on a news app? Yet sometimes bite-sized doesn’t work. I want to share an example from my own reading. At the end of 2023 and the start of 2024, I was following the Israeli offensive in Gaza the way I usually follow news media. Which is to say, I mostly read headlines and saw photos. I knew something shocking was happening, but that very sense of shock sent my brain into short-circuit. I couldn’t stay with the story; I couldn’t understand it. Then my friend and research partner, Claire Squires, told me about a book she had just read: Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide by Atef Abu Saif. The Palestinian Authority’s Minister for Culture, Abu Saif was visiting Gaza from the West Bank with his 15-year-old son when the bombing started. Don’t Look Left is his diary of the next 85 days, shared with his publisher through WhatsApp messages and voice memos. Reading this book clicked with me in a way other media hadn’t. Over the course of its 288 pages, I got to know Abu Saif, his extended family and his friends. The diary format and the ever-present threat had the immediacy and urgency of news media, but the way the diary unfolded helped me to see people and places in a new way. I learned the names and nuances of different neighbourhoods – like Jabalia refugee camp, where the author was born in 1973, and the tent city of Rafah. Abu Saif conveyed what it was like to make daily decisions about where it was safe to sleep. He describes seeking out the most fortified parts of a building, lying awake listening to missiles. I gained insight into the harrowing quiet moments between bombings, staring out shattered windows at night. The texture of everyday life and survival amid terror – searching for food, finding somewhere to charge batteries, checking messages from friends and family, helping neighbours search the rubble of bombed buildings – was woven into something profound that has stayed with me. Since reading Don’t Look Left, I have been able to remain engaged when the news feels overwhelming, to place the ongoing horrors in Gaza into a framework of deeper understanding. Aesthetic and moral Reading may sometimes seem invisible or quiet, but it is a highly dynamic activity, infused with energy. In my book, What Readers Do, I explain that reading is both aesthetic and moral. Reading Don’t Look Left had an aesthetic dimension, because its narrative structure offered me a shape I could recognise and a pace I could absorb. It aligned with my brain and helped me find meaning in the world around me. It also had a moral dimension, because it enabled me to empathise with others. The book helped me see Gaza at eye level, as a person walking through its alleys and buildings, not just as a series of aerial images. Books remain powerful. Amid all the offerings of digital media – from bingeable shows to news blogs and funny videos – reading still has a place for many of us. Adaptable and enduring, books have not been replaced by new media, but sit alongside them: they circulate not only in print form, but as audiobooks and online serials; they are adapted for other media. Globally, the book publishing industry generated US$132.4 billion in 2023, more than the movie and music industries, though less than video games. The figure has stayed steady for many years. Book festivals proliferate and celebrities run book clubs on Instagram. Book sales surged during the COVID pandemic. And book reading is not just for one demographic. While many studies suggest a majority of readers are highly educated women, reading cuts across ages and cultural groups. A 2021 report on US reading habits by Rachel Noorda and Kathi Inman Berens, for example, found that avid book engagers were younger and more ethnically diverse than the general survey population. Reading a book can involve both aesthetic conduct and moral conduct. Daniel Tadevosyan/Shutterstock Solitary and social As books persist and develop, so do reading practices. The moral and aesthetic dimensions of reading occur in a range of different settings. Reading can take place alone, but it can also be sociable. It is a practice that sometimes includes digital technology, and sometimes eschews the digital in favour of print. Readers act aesthetically when they use books to give their lives style or structure. For example, people are drawn to different genres, like poetry or crime fiction, that resonate with their sense of life’s shape. I looked to Don’t Look Left for a narrative form that was meaningful to me. Other people might seek out beautiful language, complex characters or heroic quests. Readers also engage in aesthetic conduct when they visibly identify as bookish: posting curated shelves on Instagram, cosplaying as a favourite character, or carrying a Penguin Books tote bag. The books people read find their way into how they live their life. Readers can use books to test ideas of right and wrong. Some books pose moral dilemmas that readers can use to refine their own position. Richard Osman’s most recent Thursday Murder club book The Last Devil to Die, for example, raises the issue of assisted dying. Readers can also use books to develop the moral capacity of empathy by seeking out writers with perspectives that are new to them. For example, I am one of over 41,000 followers of the Blackfulla Bookclub on Instagram, led by Teela Reid and Merinda Dutton, which highlights First Nations writers and storytellers. People connect books to their personal and political views, and express those views through social interactions. On social media, readers sometimes engage in moral conduct by expressing views on the behaviour of authors, publishers or others involved in book culture. Maybe this is “cancel culture” – or maybe it is simply activism and influence. But reading can also happen quietly and alone. For some, private reading can be a sensory, even erotic pleasure: inhaling the smell of a book, lying on the beach or the grass. For others, private reading can be training in sustained attention, “deep reading” that helps the brain. And for others, it can be a form of mindfulness, a restorative balm that counters the overwhelming aspects of modern life. Reading, on its own, can’t solve every problem. But it can help us gather the resources we need to live in a way that is meaningful. It can be a practice that helps us make sense of the world and our place in it.

Beth Driscoll, Associate Professor in Publishing and Communications, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Beth Driscoll, Associate Professor in Publishing and Communications, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

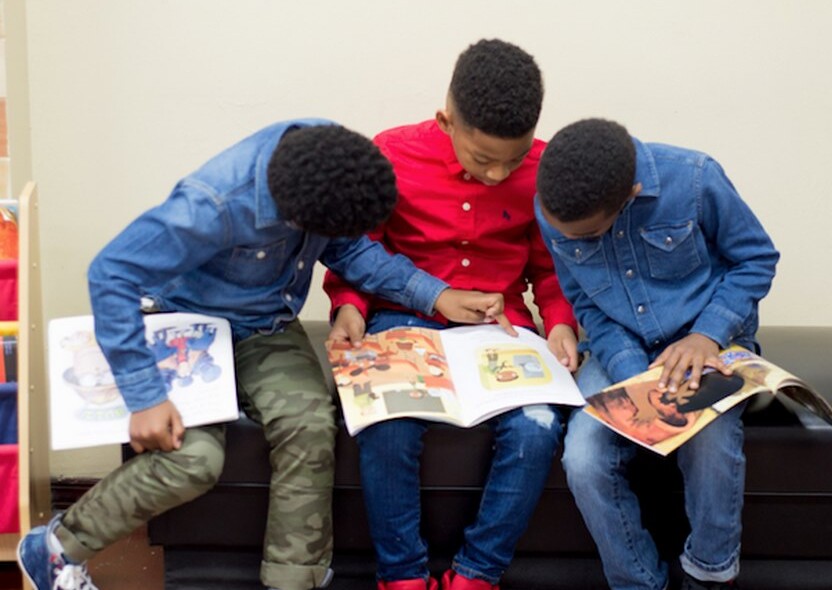

CNN Hero: Man Helps Barbers Fill Their Shops with Books to Help Kids Find Excitement in Reading

released – Barbershop Books One day in the Bronx, a first-grade teacher sat down in a barbershop for a trim and one of his students walked in, sat down, and started looking antsy. He thought to himself that it was a perfect opportunity to practice reading, a thought that changed Alvin Irby’s life, and in five years’ time, he’s filling dozens of barbershops around the country with free books to trim back childhood illiteracy. His non-profit, Barbershop Books, has delivered 50,000 free books to more than 200 barbershops in predominantly black neighborhoods in 24 states, leveraging the fact that in Black American communities, barbershops are like community centers where people congregate naturally. “Barbershop Books inspires Black boys and other vulnerable children to read for fun,” Irby told CNN, which recently honored the man as a CNN Hero. “We install a child-friendly reading space in the barbershop.” Key to the reading spaces are bookshelves that display the covers of the books rather than the spines, helping kids who may be interested in reading seize the opportunity for themselves, whether they’re in the barber’s chair or they’re waiting on their dad or friend. Irby teaches the barbers in all the shops how to help encourage kids to read, such as by asking if they like to read, or what they think about one of the books in the shop. The barbers are key for another reason as well. “We are putting books in a male-centered space,” Irby told CNN. “Less than 2% of teachers are Black males and many Black boys are raised by single moms. Black boys don’t see Black men reading.” At heart, the idea is not just about enriching a child’s mind but improving their proficiency in school, where Irby who teaches kindergarten and first grade says is pretty much the only place kids see reading happening. He says that if the only time a kid practices piano is at the piano lesson, his progress is going to be really, really slow. At the moment, he’s developing a school curriculum addition to help students identify their own reading preferences. Keeping the theme within Black culture, the program is called “Reading So Lit.” Helping pre-K to 5 students explore, understand, and articulate their reading preferences increases self-awareness and social awareness, and Reading So Lit uses self-assessments and AI to generate actionable, strengths-based data about the reading content and conditions that students find personally meaningful and engaging. It’s already been successfully trialed in schools.As sophisticated as the program is, Irby’s passion is still derived from interactions like the one which started it all—the kind that take place in the barbershop. CNN Hero: Man Helps Barbers Fill Their Shops with Books to Help Kids Find Excitement in Reading

|

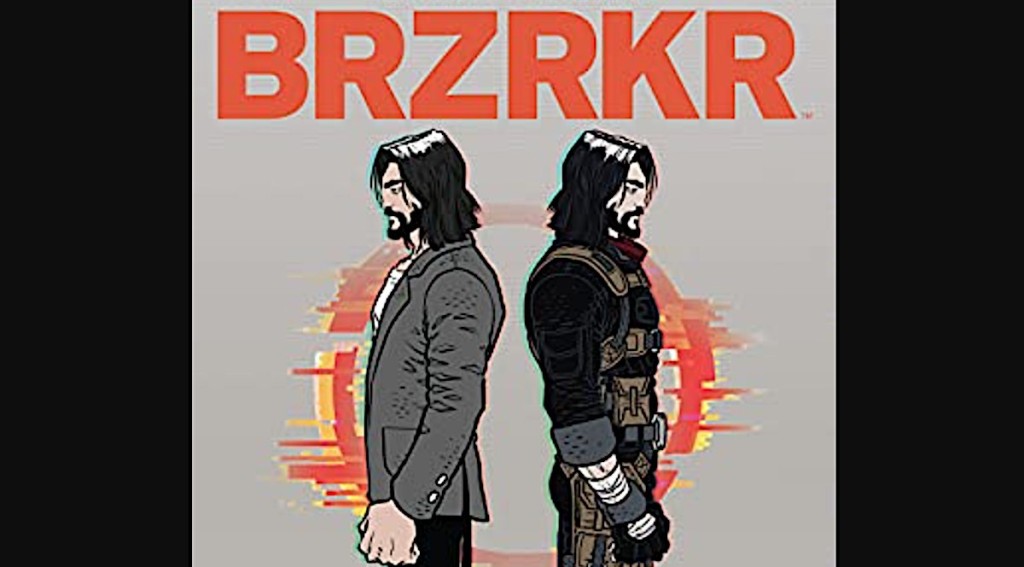

Keanu Reeves Creates Comic Books with New Superhero

Keanu Reeves Creates Comic Books with New Superhero that Kinda Looks Like Him Keanu Reeves made his comic book writing debut recently with BRZRKR, an exceptionally-violent graphic novel about an immortal warrior’s blood-fueled quest about the truth to his existence. Launched in 2021 with acclaimed illustrator Ron Garney, and co-written with New York Times bestseller Matt Kindt, it was the highest selling comic book launch in 30 years, and volume two hit shelves two weeks ago. “I love telling stories,” Reeves said recently on Jimmy Kimmel’s show, adding that he had always read comic books as a kid, and gradually selected those most appropriate for his age group. He said he enjoyed the classics: Superman, Batman, Spiderman at 12-14 years of age, but switched to Frank Miller’s more violent work, such as The Wolverine, after that. Noticing that the main character, an immortal 80,000-year-old warrior looked an awful lot like Reeves, Kimmel asks if that was by design, to which Reeves began nodding his head like a 6-year-old who was just asked if he wanted an ice cream cone. Ron Garney drew all the art for the new volume on paper, rather than digitally on a computer, which Reeves said gave it an authentic feeling.“It’s cool. There’s some action, some pathos,” Reeves said towards the end of the interview, after Kimmel had tried to push the Canadian Reeves into pursuing American citizenship, even going so far as to pull out the State Dept. forms.Keanu Reeves Creates Comic Books with New Superhero that Kinda Looks Like Him

|

Friday essay: romance fiction rewrites the rulebook

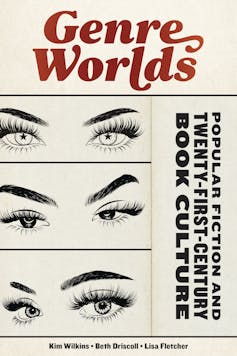

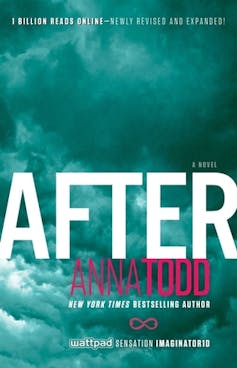

The Kiss - Francesco Hayez (1859). Wikimedia commons Beth Driscoll, The University of Melbourne and Kim Wilkins, The University of Queensland The Kiss - Francesco Hayez (1859). Wikimedia commons Beth Driscoll, The University of Melbourne and Kim Wilkins, The University of QueenslandRomance fiction has one of the most recognisable brands in book culture. It is known for a handful of attributes: its happy-ever-after endings, the pocket Mills & Boon and Harlequin editions, the covers featuring Fabio (in the 1990s) or naked male torsos (the hot trend in the 21st century). It is known for being overwhelmingly written and read by women, and for being mass-produced. But romance fiction is also the most innovative and uncontrollable of all genres. It is the genre least able to be contained by established models of how the publishing industry works, or how readers and writers behave. Contemporary romance fiction is challenging the prevailing wisdom about how books come into being and find their readers. For our book Genre Worlds: Popular Fiction and Twenty-First Century Book Culture, coauthored with Lisa Fletcher, we conducted nearly 100 interviews with contemporary authors and publishing professionals. Our research shows that fiction genres are not static. They do not constrain artistic originality, but provide the kind of structure that sparks creativity and passion. Genre fiction can be understood as having three dimensions. The textual dimension is what happens on the page. The industrial dimension is how the books are produced. And the social dimension is the people who write, read and talk about genre fiction. These three dimensions interact to create what we have called a “genre world”. Each distinct genre world (such as fantasy or crime) combines textual conventions, social communities and industry expectations in its own way. And romance is the most fast-paced, rapidly changing genre world of them all. When it comes to genres of articles, we have a soft spot for the listicle. So, here are five things you may not know about contemporary romance fiction – five things that show the dynamism at the heart of book culture. 1. Romance is at the forefront of digital innovation: Twenty-first century publishing has seen fundamental shifts in the way books are produced, distributed and consumed, largely thanks to digital technology. The romance genre is notable historically for its rapid production and consumption cycle. As a result, it has been well placed to adapt to the widespread uptake of digital publishing, which also moves rapidly. Romance writers and publishers are entrepreneurial and comfortable taking risks. The moment constraints are released, romance writers rush in. This is exactly what has happened with self-publishing. Since the advent of Kindle Direct Publishing in 2007, hundreds of thousands of romance books have been self-published there. Other opportunities have blossomed on sites such as Wattpad or through print-on-demand services such as IngramSpark. In Australia, for example, there was a 1,000% increase in the number of self-published romance novels between 2010 and 2016.  Some self-published romance novels have achieved mind-boggling success. Anna Todd’s 2014 romance novel After, originally fan fiction based on the band One Direction, drew more than 1.5 billion reads on Wattpad. It was subsequently acquired by Simon & Schuster and has spawned a movie series. In other cases, romance authors have formed co-ops to publish work together. Tule Publishing is a small, largely digital publisher with a limited print-on-demand service that produces multi-author continuity series as part of its publishing model. The Tule authors we interviewed spoke of their strong community and creative connections. The self-publishing of genre fiction has blurred the lines between author, agent, editor, cover designer, typesetter, publisher and bookseller. Stephanie Laurens, one of the world’s most successful romance novelists, began writing with Mills & Boon before moving to HarperCollins. In 2012, she gave a keynote address to the Romance Writers of America convention. She used the opportunity to reflect on industry change. Soon after, she began reconfiguring her own publishing arrangements. Now Harlequin publishes her print novels, while she self-publishes the e-book versions. She also self-publishes novellas that are prequels to, or that sit between, the novels in her traditionally published series. Laurens is a prolific author with loyal fans, an author who can afford to take risks. She realises that self-publishing potentially offers her a better deal and has been able to pursue that while retaining ties to a traditional publisher. Her career complicates any view of self-publishing as second best. Her example has been much emulated among romance writers. Such a career move challenges how we might typically theorise the power relations of literary culture. 2. Romance readers are active and engaged: The dynamism of romance fiction is intimately linked with its engaged readers. Unlike other kinds of publishing, where the fate of each book is relatively unpredictable, romance has historically had many loyal readers who subscribe through mail-order systems to receive books regularly – a model that has not worked successfully at scale for any other genre. In the 21st century, many of these loyal romance readers are online. They tweet about their favourite authors, write Goodreads reviews, and run blogs and podcasts.  People read romance fiction for different reasons. They might be drawn to its focus on the emotional nuances of relationships, its escape into various times and places (romance subgenres really do cover the gamut), or its gold-plated promise of happy endings and pleasure. They might read casually or intensely, with curiosity, scepticism or devotion. All of these are active modes; they can’t be reduced to consumerism. There is an element of feeling to the involvement. The shared pleasure and sense of belonging that comes with being in the genre world came up regularly in our interviews. Author Rachael Johns, speaking of romance fiction, said “this is my passion, I fell in love with the romance genre”. Agent Amy Tannenbaum described the romance community as “tight-knit”. Harlequin marketing specialist Adam Van Roojen suggested the romance community’s supportive nature makes it “so distinctive I think from other genres”. People say the same thing about other genres, of course, but these claims show how people imagine genre worlds as a kind of community. Communities have boundaries and can be exclusionary. Kristina Busse has written about the impulse to police borders in fan-fiction communities, and of how ascribing positive values to some members of a community may exclude other people. This dynamic is at work in genre worlds, even if it is low-key or not openly acknowledged. What’s more, the inside world of romance fiction has an inside of its own. This is evident in the way readers relate to one another (there is an implicit hierarchy of fans) and in the industrial underpinnings of the genre. For example, there is a distinction between a writer’s core audience and fringe audience that affects sales formats and international editions. Core romance readers tend to read digitally, and therefore can often access US editions of a book. Casual romance readers are more likely to pick up a print book from a store like Big W or Target and are therefore more likely to be the target audience for local editions. In general, though, both core and fringe romance readers know how to read romance fiction. They are attuned to the codes that run through the novels. Back in 1992, Jayne Ann Krentz and Linda Barlow argued that certain words and phrases in romance fiction act as a hidden code “opaque to others”. Committed romance readers have a deep knowledge that makes them experts in their genre. When these readers express their views online, authors and publishers take note. One recent example involves a tweet from romance fiction author, podcaster and blogger Sarah McLean. She asked her nearly 40,000 Twitter followers to “Tell me the best romance you’ve read in the last week. Bonus points for it being 🔥🔥🔥.” The tweet was directed at the hardcore readers of the romance genre world. It assumed an audience that reads more than one romance novel per week. The 300 or so replies constitute a mega-thread of recommendations. Romance readers are generous to one another this way, as the sheer abundance of commercially and self-published romance fiction makes it hard to sort and choose. The replies also offer an up-to-the-minute map of the subgenres and tropes to which readers are responding. These include shape-shifters, second-chance love stories, queer romance, and dukes and duchesses (possibly a Bridgerton effect). 3. Romance fiction is global: Far from being circumscribed by small horizons, romance fiction is globally connected and inflected. This is amply demonstrated by the example of Australian romance fiction, which is formed and sustained across international literary markets and creative communities. Pascale Casanova’s theory of the world republic of letters notes the cultural force of London and New York as anglophone publishing centres. This mitigates against the inclusion of Australian content in popular fiction. Stories set in New York or London seem to have no limits in terms of international portability. But stories set in Australia, or another peripheral market, can be harder to pitch. Australian writers are conscious of this, as it directly affects the viability of their careers. But export success is possible for Australian work. The subgenre of Australian rural romance or “RuRo” is the best-known example. Authors like Rachel Johns are bestsellers in other territories. Romance novels set in Australia are popular in Germany – the Germans even have a name for them, the “Australien-Roman”.  Popular Australian romance author Rachel Johns. Goodreads Romance fiction is energised by transnational communities of readers and writers, often mediated online. Australian romance author Kylie Scott, for instance, credits American romance bloggers with driving the popularity of her books, and thanks book bloggers in the acknowledgements of her books.  These cultural mediators assist the transnational movement of books in genre worlds. The development of digital-first genre fiction publishers and imprints also supports such movement, not least through promoting global release dates and world rights, so that genre books can be simultaneously accessible to readers worldwide. But nothing comes close to the romance fiction convention, or “con”, in demonstrating the international cooperative links of the romance community. Cons, such as Romance Writers of America, support romance writers by providing professional development opportunities; they offer structure to participants’ professional lives. For example, Regency romance writer Anna Campbell has oriented her career towards the United States. Campbell began to professionalise by joining the Romance Writers of Australia, but then entered professional prizes run through US networks, and it was these that gained attention for her writing and enabled her to get an agent. American success followed: My agent ended up setting up an auction in New York, and three of the big houses wanted to buy it. The auction went for a week, and at the end of Good Friday 2006, I was a published author and they paid me enough money to become a full-time writer. Campbell went on to write five books with Avon, then moved to Hachette for a number of books. She has now moved to self-publishing. The majority of her readership remains in the US. Romance’s capacity to reflect the local concerns of writers and readers, coupled with its responsiveness to global industrial processes, makes it one of the most intriguing genres for considering what “Australian books” might look like in the 21st century. 4. Romance can be socially progressive It has been more than 50 years since Germaine Greer, in The Female Eunuch, dismissed romance fiction as women “cherishing the chains of their bondage”. The perception that the genre is conservative persists. But romance writers and readers are more and more concerned with inequality across gender, race and sexuality. They are pushing back against old conventions. In 2018, Kate Cuthbert, then managing editor of Harlequin’s Escape imprint, gave a speech that revealed romance’s internal debates. She addressed the responsibilities of romance fiction writers and publishers in the #MeToo era, arguing that if we want to call ourselves a feminist genre, if we want to hold ourselves up as an example of women being centred, of representing the female gaze, of creating women heroes who not only survive but thrive, then we have to lead. For Cuthbert, this means “breaking up” with some familiar romance fiction tropes, such as the coercion of women: many of the behaviors that are now being called out – sexual innuendo, workplace advances, stolen kisses because the kisser couldn’t resist – feel in many ways like an old friend. They exist in the romance bubble […] and they readily tap into that shared emotional history over and over again in a way that feels familiar and safe. Cuthbert’s compassionate acknowledgement of readers’ and writers’ attachment to established genre norms sits alongside her call for evolution, for renewed attention to “recognising the heroine’s bodily autonomy, her right to decide what happens to it at every point”. Structural hostility in the publishing industry towards people of colour has also become a cause romance writers and readers rally behind. In 2018, Cole McCade, a queer romance writer with a multiracial background, revealed that his editor at Riptide had written to him: We don’t mind POC But I will warn you – and you have NO idea how much I hate having to say this – we won’t put them on the cover, because we like the book to, you know, sell :-(.In the wake of this revelation, multiple authors pulled their books from Riptide, as a further series of revelations about the publisher’s bad behaviour emerged. The following year, the Romance Writers of America examined the past 18 years of its RITA Awards finalists and published the results: no black author had ever won a RITA, and the percentage of black authors represented on shortlists was less than half a per cent. In response, the board published a “Commitment to RITAs and Inclusivity”, in which it called the shocking results a “systemic issue” that “needs to be addressed”. In 2020, they announced they were employing diversity and inclusion experts to help diversify their board, train staff, and help “design and structure” more inclusive membership programs and events, including the annual conference. The Romance Writers of America’s intentions have not always been successful. The ongoing visibility of marginalised groups in the genre continues nonetheless, in part driven by romance’s rapid and robust uptake of digital publishing. Access to publishing platforms has allowed micro-niche genres to proliferate. LGBTQIA+ romance subgenres have become particularly visible: from lesbian military romance to gay alien romance to realist asexual love stories.  Sometimes these stories go spectacularly mainstream, as with C.S. Pacat’s The Captive Prince, a gay erotic fantasy about a prince who is given to the ruler of a neighbouring kingdom as a pleasure slave. Originally self-published, The Captive Prince started as a web serial that gathered 30,000 signed-up fans and spawned Tumblrs dedicated to fan fiction and speculation about where the series would go. The book was rejected by major publishers, so Pacat self-published to Amazon and within 24 hours it had reached number 1 in LGBTQIA+ fiction. A New York agent approached Pacat and secured her a seven-figure publication deal with Penguin. The queer fantasy or paranormal romance has continued to thrive in Pacat’s wake. In our interviews with romance authors, questions of diversity, inclusion, representation and inequity arose again and again. In representation and amplifying marginalised voices, romance has enormous potential to lead the way. 5. Romance has gates that are kept: Romance fiction is more progressive than some stereotypes might suggest, but it is not free from exclusion or discrimination. The genre is influenced by its gatekeepers – human and digital. One form of gatekeeping takes place through the same voluntary associations that nurture community. In late 2019, the board of the Romance Writers of America censured prominent writer of colour, Courtney Milan, suspending her from the organisation for a year and banning her from leadership positions for life. The decision was made following complaints by two white women, author Katherine Lynn Davis and publisher Suzan Tisdale, about statements Milan had made on Twitter, including calling a specific book a “fucking racist mess”. This use of the organisation’s formal mechanisms to condemn a woman of colour and support white women was controversial, provoking widespread debate across social media and email lists. Milan had long been an advocate for greater inclusion and diversity within Romance Writers of America and the romance genre. As the Guardian reported, the choice not to discipline anyone for “actually racist speech” made punishing someone for “calling something racist” seem like a particularly troubling double standard. “People saw it as an attempt to silence marginalised people,” observed Milan. The board retracted its decision about Milan. It is difficult, however, to calculate the damage that may have been done to readers and writers of colour in the romance genre world. Conversely, the use of Twitter to extend debate and eventually correct the Romance Writers of America shows change happening, in real time. Another form of gatekeeping in romance fiction happens through the same digital platforms that put the genre at the forefront of industry change. Safiya Umoja Noble’s book Algorithms of Oppression demonstrates how apparently neutral automated processes can work against women of colour — for example, the different results that come up from a Google search of “black girls” compared with “white girls.” In the world of romance fiction, Claire Parnell’s research has shown the multiple ways in which the algorithms, moderation processes and site designs of Amazon and Wattpad work against writers of colour. For example, they make use of image-recognition systems that flag romance covers with dark-skinned models as “adult content” and remove them from search results. They can also override the author’s chosen metadata to move books into niche categories where fewer readers will find them, such as “African American romance” rather than the general “romance fiction”. Concerted activism and attention is needed to work against this kind of digital discrimination, which risks replicating the discrimination in traditional publishing. There is no simple way to account for the dynamics of contemporary romance fiction. It is inclusive and policed; it is public and intimate. Its industrial, social and textual dimensions are not static, but interact dynamically, incorporating the possibility of change. Only by understanding these interactions can we gain a complete picture of the work of popular fiction. Contemporary romance fiction is formally tight, emotionally intense and digitally advanced. It’s where the heartbeat of change and action is in book culture. Beth Driscoll, Associate Professor in Publishing and Communications, The University of Melbourne and Kim Wilkins, Professor in Writing, Deputy Associate Dean (Research), Faculty of HASS, The University of Queensland, The University of Queensland This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

After Collecting Over 8000 Titles, Woman Fulfills Dream of Opening a Bookstore While Recovering From Diagnosis

While youth is often a time of great promise and achievement, a life well lived can also be filled with any number of next chapters and second—or even third—acts that add depth, nuance, and meaning to our stories. At 65 years old, Somerset native Carole-Ann Warburton experienced a plot twist that led to the fulfillment of a long-cherished dream she’d never even spoken of aloud. After a debilitating illness incapacitated her, Warburton was left with the question of what to do going forward. During her convalescence, her daughter brought around some real estate listings for the sort of homes in which she thought her mum might best spend her golden years. Coincidentally, amongst the notices was an offering for a small barbershop with an above-stairs apartment. For Warburton, although she admits “the place was awful,” it was love at first sight—and the perfect opportunity to do something she’d yearned to do for almost as long as she could remember—work in a bookshop. Less than three months after coming to her decision, Warburton had handed in her retirement notice, sold her house, bought the store, and—using a personal inventory totaling between 8,000 to 9,000 titles—she launched her new venture, The Book Rest. Warburton has been an avid book collector since she was a child. As an adult, she married a man with a similar avocation. The four-bedroom home she and her ex-husband shared with their children (much to their dismay) was “chock-a-block” with books. Warburton admits learning to let go of her beloved tomes was a bit of an adjustment, but one she feels the better for making. “It still feels, when a special book goes out, like a bit of a loss—as if some little part of me has been taken away,” she said in an interview with The Guardian. “And then I make common sense come back to me and say, ‘Let someone else learn from it.’ It’s a growing up, if you like, an acceptance.” A decade on, The Book Rest recently celebrated its 10th anniversary. Although the pandemic has slowed foot traffic, since Warburton’s driving motive isn’t monetary profit, but rather, something of a deeper, more idiosyncratic personal value, she has no plans to close up shop. Having achieved her own dream, Warburton sees every day in the bookstore as an opportunity to help others realize theirs as well. “All the dreams are in the books,” she told The Guardian. “They are all there waiting to be picked up… Someone can walk in tomorrow and say, ‘I have been looking for that for an awfully long time!”And as gatekeeper to her own small universe of literary wonders, Warburton says she plans to stay around as long as she can to ensure that they do.After Collecting Over 8000 Titles, Woman Fulfills Dream of Opening a Bookstore While Recovering From Diagnosis

|

Book Review: ‘Hunted’

|

“HUNTED” by Abir Mukherjee. (MUST CREDIT: Mulholland) The setup may sound familiar, but “Hunted,” the new thriller from Abir Mukherjee, offers a welcome alternative to the typical cops-and-robbers thriller. Days after a terrorist organization kills dozens of people in a Los Angeles shopping mall, law enforcement officials arrest Sajid Khan at his place of employment in London and ruthlessly interrogate and beat him, seeking information about his 18-year-old daughter. This is how Sajid discovers that his beloved daughter, Aliyah, is a key figure in a dangerous terrorist network. When, a few days later, an American woman named Carrie Flynn finds Sajid and explains that her son has a connection to Aliyah and may also be involved with the terrorists, Sajid and Carrie embark on a perilous journey to America to save their children. This plotline – a terrorist attack on the United States sets off a hunt-and-chase that affects the lives of ordinary people and reveals cracks in the political and social structure of the country – has been written and rewritten endlessly by writers like Vince Flynn, Lee Child and Brad Thor. Mukherjee keeps readers in that well-worn (and beloved) territory while also elevating his tale beyond expectations. He dives deeply into the stories of the families of the assailants – the anguish and anxiety experienced by their horrified parents, and the rash decisions they are compelled to make. And he does this without abandoning the rush of a thriller or the complexities of law enforcement – particularly through the character of Shreya Mistry, an FBI agent who consistently defies her superiors in her hopes to stop the next attack on American soil. Mukherjee offers some keen observations, and his everyday heroes are a nice reprieve from the hypermasculine killing machines we typically come across in such books. In his efforts to describe the uneasy political climate in contemporary America, Mukherjee does not shy away from the chaos of real-life politics or pertinent social issues. References are made to the 2016 election and the heartbreak brought on by the 2017 Muslim travel ban. More than simply observing these events, Mukherjee’s characters are particularly well-suited to offer commentary and insight into them, especially Sajid, a Muslim refugee of political violence in Bangladesh, and the most clear-eyed and compassionate of the protagonists. Upon learning about the attack in Los Angeles, Sajid notes with concern that, “It was taken as fact that the attackers would be Islamists, and suddenly a few hundred extremists with a death wish were taken as proxy for a billion people.” America, in fact, is observed in almost Tocquevillian fashion as the protagonists race through the country. When passing poverty-struck towns in the Midwest, Sajid wonders, “There had been prosperity here … and yet it had gone. What did that do to people? To be masters of the world and then reduced to poverty? Would it engender anger? Fear?” When he later observes an American political rally, Sajid compares the event to its British counterpart and notes, “While there was certainly something to be said for the enthusiasm and engagement of the American model, without trust or an informed electorate, did it not lead to tribalism?” These observations, along with forays into familial and romantic drama, never slow the book’s pace. Mukherjee has a knack for ending chapters on earned cliffhangers. Plot twists are largely presented without the strain of incredulity, the suspense is always weighted with emotion, surprising revelations are carefully constructed – and the ending is unexpected, daring and truly beautiful. “Hunted” marks Mukherjee’s first stand-alone novel after the popular and critically acclaimed Wyndham & Banerjee Mysteries, and fans of those historical mysteries probably won’t be disappointed by the author’s turn to contemporary thrillers. Even if the book treads on familiar territory, Mukherjee proves he has more than enough talent, compassion and insight to tell a compelling, unique story. – – –E.A. Aymar is author of the thrillers “They’re Gone,” “No Home for Killers” and “When She Left.”Book Review: ‘Hunted’ has the rush of a thriller without the unnecessary violence

|

A Book-Lovers Tour of Britain: From The Bard to the Brontës, Sherwood Forest to Sherlock Holmes: The Top 35 Stops

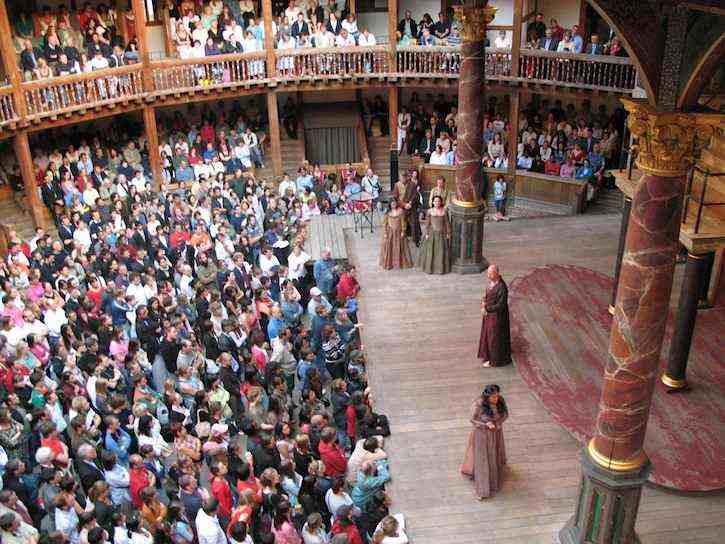

OnePoll / SWNS / Kindle Storyteller Award OnePoll / SWNS / Kindle Storyteller AwardA poll of 2,000 literary lovers in Britain has revealed the top 35 places to visit made famous by iconic authors and the scenes from their books. Some of the top must-see locations for book buffs are right in London, including Shakespeare’s Globe theater, the John Keats home, and 221-B Baker Street, better known as the home of Sherlock Holmes. Travel 56 miles (90 km) northwest of London to Oxford, and tip a pint of ale at the Eagle and Child Pub, where authors JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis, who created the mystical realms of Middle Earth and Narnia, held regular meetings on Thursday evenings with their writers’ group The Inklings. Further into the countryside of West Yorkshire, visit Haworth, the #1 most beloved literary stop. It was the home of the Brontë sisters and its moorland setting had a profound influence on the writing of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. Many of the sites, like Haworth, also have museums located on the property. Sherwood forest, with its historic connection to the legend of Robin Hood, and Shakespeare’s birth town of Stratford-upon-Avon, also joined Jane Austen’s Chawton cottage in Hampshire in the top 35 ranking (see full list below).  Globe Theater in London Globe Theater in London“Iconic locations such as Shakespeare’s Globe and the home of the Brontë sisters hold such cultural importance, and it’s great to see them feature so prominently in our research,” said Darren Hardy, author and editorial programs manager at Amazon, which commissioned OnePoll to carry out the survey to launch the Kindle UK Storyteller Award, celebrating the best self-published stories. The University of Oxford English Literature Professor Elleke Boehmer said the British Isles are rich in vital literary traditions. “In Britain, you almost get the sense in some literary places of the land, trees and surroundings pregnant, still, with the writer’s presence, or a sense of how they have interacted with the context—like Coleridge’s Quantock hills. “The walks that he made through those hills still exist today, and as we walk them we can imagine him pacing out the lines of his poetry, like ‘The Ancient Mariner’, looking out onto the Bristol Channel at the passing ships from around the world. “Some of my favorite literary sites, like Coleridge’s Nether Stowey, the Brontës’ Haworth or DH Lawrence’s Eastwood, also feature truly wonderful and significant houses where the rooms in which the writers were born, or wrote some of their key works, are preserved for all generations.” The poll also asked people to name their favorite British writers—Charles Dickens came out on top, followed by Charlotte Brontë and George Orwell. TOP 35 LITERARY LOCATIONS IN THE UK

The Kindle Storyteller Award is a £20,000 literary prize recognizing outstanding writing, open to authors publishing in English in any genre through Kindle Direct Publishing. Readers play a significant role in selecting the winner, helped by a panel of judges including various book industry experts. The 2024 Kindle Storyteller Award will be open for entries between 1st May and 31st August 2024. “We are looking forward to seeing what stories are submitted for this year’s Kindle Storyteller Award – perhaps some will have been inspired by some of our iconic literary landmarks and the authors connected to them.”A Book-Lovers Tour of Britain: From The Bard to the Brontës, Sherwood Forest to Sherlock Holmes: The Top 35 Stops

|