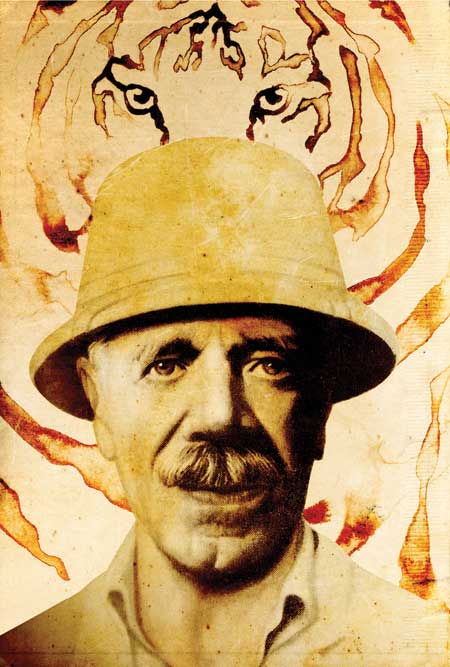

Stephen Alter reimagines the enigma of Jim Corbett : In the Jungles of the Night: A Novel About Jim Corbett | Stephen Alter | Aleph | 193 Pages | Rs 499

by Janaki Lenin (Janaki Lenin writes on wildlife conservation. Her latest book is My Husband and Other Animals,) AN AUTHOR fascinated by man-eater slayer Jim Corbett has a tough task. At least four biographies of the famed hunter of man-eaters and bestselling author exist. His fans have written blog posts, articles and books on him, even pinpointed locations mentioned in his books. So how can a writer approach the subject with a fresh perspective?

Faced with the quandary, Stephen Alter switched genres: he fictionalised his subject. The result is In the Jungles of the Night: a novel about Jim Corbett, the title excerpted from William Blake’s The Tyger.

Alter writes fiction and non-fiction books with equal deftness. Based on what Jim reveals of himself in his books and DC Kala’s biography Jim Corbett of Kumaon, Alter’s novel has three sections, portraying a 13-year-old Jim, a seasoned hunter, and an elderly émigré.

The teenage Jim in Alter’s imagination is a fern collector, a solitary pursuit, much like hunting big cats. On the quest for a rare species, the boy discovers the desecrated coffin of a young woman. Ten years earlier, the 19-year-old lady had been killed and the police and community believe the culprit to be a man-eating leopard. Soon afterwards, Jim’s elder brother, Tom, kills a leopard thought to be the assailant. But now, after the sacrilege is uncovered, Tom hints to his brother that there may be more than meets the eye.

An intrigued Jim investigates the spot where her body was found. Even at that age, he reads tracks like he would later as a hunter. His keen observations aid the police in uncovering what happened to the woman.

Alter, born in India of American parents, shows how cruel English society was to its India-born compatriots. Murch, a dissolute Englishman fallen on bad times, is a third-generation White like Jim. Even before Murch’s fall from grace, his peers call him names and shun him. The reader can’t help wonder if Jim’s family faced similar discrimination. Alter offers ‘country-bottled’ Englishmen as a parallel for untouchables in Indian society. Yet, no matter how lowly some Whites were regarded, they always ranked higher than Indians.

Alter has Jim, a renowned hunter by now, go after the ‘Man-eater of Mayaghat’ in the next chapter. Set in 1926, this is the same year Jim shot the leopard of Rudraprayag, said to have killed more than 125 people and a tigress that stalked the labour camps of Sarda valley.

This 90-page-long chapter of the hunt for the man-eater is classic Corbett, although it’s written in the third person. Vivid natural history observations relieve tense sections as Jim stalks the cat through the jungle. The behaviour of terrorised labourers is reminiscent of people in today’s Sunderbans, where they routinely fall prey to tigers. After the tigress claims two more humans, Jim shoots her dead.

A couple of unusual elements set this tale apart. The lack of love interest in Corbett’s life has mystified readers. The only woman in his life was his elder sister Maggie. DC Kala, in his pop psychoanalysis, suggests an eight-year-old Jim may have been scarred while chaperoning his grown sisters as they bathed in the river. Did he love a woman? Was it unrequited love? Or did he not meet a soul mate at all? No biographer sheds light on this aspect of his life. Unfettered by real life, Alter’s Jim gets laid.

Kaiyu, Jim’s fictional woman friend, is no wallflower. She’s a toughie, living alone in the forest with no male protection. She knows the way of the wild and ventures out when others live in terror of the man-eater. This gains her the respect and concern of the 51-year-old bachelor. But when she makes the first amorous move, Jim follows.

A factor that sets Jim apart from other writers of shikar books of that time was his empathy for Indians, often those of marginalised classes. In his travels and conversations with local people, he would have known that the forest laws deprived them of their livelihoods. The extensive network of railways needed vast stands of timber trees like sal for sleepers. To safeguard these resources, the department forbade others from hunting and grazing in its forests, a traditional monopoly the institution continues to exercise today. This undercurrent of tension is missing from Jim’s books.

Alter turns up Jim’s social consciousness a notch or two, forcing him to acknowledge the travails of Banrajis, a tiny indigenous community of hunter- gatherers. The department’s deforestation is far more damaging than the small- scale hunting of indigenous people. But he doesn’t change Jim’s personality too much. Jim still sees the British administration as paternalistic and views the activities of Bimal Swadeshi, the local Congress activist, with distaste. To be fair, he has no tolerance for the bigoted Andrew Kincaid, the District Forest Officer.

Alter shows Jim isn’t the infallible hunter or the crack shot he’s thought to be. While waiting for the tigress to make an appearance, he mistakenly shoots at a leopard that scavenges a human kill even though he can’t see in the dull light of gathering nightfall. Worse, his bullet misses its target. “Too often we think of Corbett as someone who never failed and never made a mistake,” says Alter. “In his books he describes several incidents in which he missed his target or misinterpreted signals in the jungle. I suppose the episode with the leopard is meant to suggest the uncertainties of being in the dark.”

DESPITE HOW MUCH of his work occurs at night, Jim doesn’t carry a light. Not only is he in danger of becoming the man-eater’s next meal, it’s also the time when snakes bite people. If there’s one creature that he cannot stand, it’s the snake. Not only does he try to kill every single one he sees, he believes slaying one brings him luck in hunting man-eaters.

Jim entertains a host of other supernatural beliefs. In the manner of people of that time and place, Kaiyu too has her own understanding of the forest and animals. She warns that a goddess protects the man-eater, and he should placate her by offering something of himself. She speaks with such authority about the tigress’ habits, the reader and Jim wonder if she’s the goddess. The climax of the chapter is not the moment when the man-eater falls dead. After he returns to the camp, the labourers arrive with the lifeless body of Kaiyu. A panicky Kincaid had shot her when labourers demanded better pay.

Is this the ‘offering’ that appeases the goddess and the reason Jim’s bullet finds its mark?

“Perhaps,” replies Alter. “I wanted to suggest that the way [Kaiyu] understands the forest is through a sense of submitting to nature’s realities as well as its mysteries. Corbett too seems to have had this kind of empathy for nature in which he allows himself to become absorbed in the tigress’ presence, even as he tries to kill her. He certainly recognises that there may be a mystical link between Kaiyu and the tigress, even if it is nothing beyond a myth or metaphor.”

Jim could have also be offering something of himself when he submits to Kaiyu’s sexual overtures.

The last chapter’s title ‘Until the Day Break’ is taken from the epitaph on Jim’s tombstone. Alter changes voice here, going from third person to first person as if the 78-year-old Jim wrote it in Kenya.

The elderly Jim assesses his life, experiences and decisions. The chapter covers a lot of ground in a manner not unlike the elderly are known to do. Did he have to leave India? Alter foreshadows his distrust of Indians’ aspiration for self-determination in the same way Jim relates to Bimal Swadeshi. So his decision to emigrate to Kenya appears logical.

Although he enjoys the extravagant wildlife spectacle for which Kenya is renowned, Jim writes little of its people. Nor does he describe the sights and smells of the savannah as he did so wonderfully the Himalayan jungles. In Alter’s imagination, he did express at least a tinge of regret for leaving the land and people he loved.

Here too, unexplainable events occur. A goat he tethers goes missing and he finds it later in the village. Who could have set it free? Jim also swears he filmed a leopard but when the developed film returns, there’s no sign of the cat in the film. Was he hallucinating?

“I decided to tell this part of the book in his voice, a rambling raconteur who plays with the facts even as he tells the truth,” says Alter.

This triptych novel presents the enigma of Jim Corbett to another generation of readers. Read it. You won’t regret it.Source: OPEN Magazine

|