Speak

Sometimes he sounds like music to her ears. Other times, not so much.

as an undergraduate at Emory University. For male birds listening to another male’s song, it was a different story: They had an amygdala response that looks similar to that of people when they hear discordant, unpleasant music. The study, co-authored by Emory neuroscientist Donna Maney, is the first to compare neural responses of listeners in the long-standing debate over whether birdsong is music. “Scientists since the time of Darwin have wondered whether birdsong and music may serve similarpurposes, or have the same evolutionary precursors,” Earp notes. “But most attempts to compare the two have focused on the qualities of the sound themselves, such as melody and rhythm.” Earp’s curiosity was sparked while an honors student at Emory, majoring in both neuroscience and music. She took “The Musical Brain” course developed by Paul Lennard, director of Emory’s Neuroscience and Behavioral Biology program, which brought in guest lecturers from the fields of neuroscience and music. “During one class, the guest speaker was a composer and he said that he thought that birdsong is like music, but Dr. Lennard thought it was not,” Earp recalls. “It turned into this huge debate, and each of them seemed to define music differently. I thought it was interesting that you could take one question and have two conflicting answers that are both right, in a way, depending on your perspective and how you approach the question.” Perhaps your brain would enjoy some music while reading this. Here's a sample of Earp's favorite: "Firebird." As a senior last year, Earp received a grant from the Scholars Program for Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Research (SPINR), and a position in the lab of Maney, who uses songbirds as a model to study the neural basis of complex learned behavior. When Earp proposed using the lab’s data to investigate the birdsong-music debate, Maney thought it was a great idea. “Birdsong is a signal,” Maney says. “And the definition of a signal is that it elicits a response in the receiver. Previous studies hadn’t approached the question from that angle, and it’s an important one.” Earp reviewed studies that mapped human neural responses to music through brain imaging. She also analyzed data from the Maney lab on white-throated sparrows. The lab maps brain responses in the birds by measuring Egr-1, part of a major biochemical pathway activated in cells that are responding to a stimulus. The study used Egr-1 as a marker to map and quantify neural responses in the mesolimbic reward system in male and female white-throated sparrows listening to a male bird’s

"Bullfinch male" by © Francis C. Franklin / CC-BY-SA-3.0. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

a new study by According the late Nicolai Jurgen and researchers from the University of Kaiserslautern in Germany, the analysis of human melody singing in bullfinches gives insights into the songbirds' brain processes. The songs of free-living bullfinches are soft and contain syllables that are similar to the whistled notes of human melodies. Teaching birds to imitate human melodies was a popular hobby in the 18th and 19th centuries and the bullfinch was the favourite species. Using historical data recorded for 15 bullfinches, hand-raised by Jurgen Nicolai between 1967 and 1975, the researchers studied whether the bullfinches memorized and recalled the note sequence of the melodies in smaller subunits, as humans do, or in their entirety, as a linear chain, which is much simpler. They also analyzed the accuracy of the bullfinch's choices and how a bird continues to sing after the human partner pauses. They focused

"Pyrrhula pyrrhula -Lochwinnoch, Renfrewshire, Scotland-8" bi Mark Medcalf - Bullfinch Uploaded by snowmanradio. Licensed unner CC BY 2.0 bi wa o Wikimedia Commons.

on whether the bird chooses the right note sequence at the right time - so-called alternate singing. When birds sing solo, they do not retrieve the learned melody as a coherent unit, but as modules, containing much smaller sub-sequences of 4-12 notes. The researchers investigated the cognitive processes that allow the bullfinch to continue singing the correct melody part when its human partner stops. They found evidence that as soon as the human starts whistling again, the birds can match the note sequence they hear to the memorized tune in their brain. They anticipate singing the consecutive part of the learned melody and are able to vocalize it at the right time when the human partner stops whistling. The authors said that the Bullfinches can cope with the complex and demanding cognitive challenges of perceiving a human melody in its rhythmic and melodic complexities and learn to sing it accurately. The work has been published online in Springer's journal Animal Cognition. (ANI). Source: Article, Golden Whistler Australia Birds: The Norfolk Island subspecies

of Golden Whistler prefers the shrubby understorey of rainforest, palm forest and local pine forest (Smithers and Disney, 1969), but also uses plantations of exotic species. It has been recorded in, or at the edges of, pockets of suitable habitat throughout the island, but does not occur near gardens (Schodde et al., 1983). There are about 70 other subspecies in other parts of Australia and on islands in the south-west Pacific Ocean. P. p. contempta (Lord Howe I.) is Vulnerable. All other Australian subspecies (Schodde and Mason, 1999) are Least Concern, including P. p. queenslandica (wet tropics), P. p. pectoralis (central Queensland to northern New South Wales), P. p. youngi (south-eastern mainland Australia), P. p. glaucura

(Tasmania) and P. p. fuliginosa (mallee regions). Largely confined to the Norfolk Island National Park and nearby forested areas. A steady decline recorded through 1960s and 1970s, but subspecies still present over nearly half the island in 1978 (Schodde et al., 1983). By 1990, virtually confined to Norfolk Island National Park (Bell, 1990) and the population reduced to 535 pairs (Robinson, 1988). Recent estimates suggest the population has now stabilised (Robinson, 1997). Much suitable habitat has beencleared or fragmented, and the subspecies appears to be confined to

the largest tract of remaining forest. The reason for the recent population decline, and the principal continuing threat is probably predation by Black Rats Rattus rattus (introduced in the mid 1940s; Robinson, 1988). Cats may also take some birds (Bell, 1990). The Golden Whistler lives in forests throughout Lord Howe I., and nests high in the trees away from most predators. Golden Whistlers have survived the introduction of cats, rats, pigs and goats to Lord Howe I. Therestricted area of occupancy, however, makes the subspecies susceptible to catastrophe, such as the introduction of another predator. Source: Article. Doing the math for how

A baby house finch and its father. Just like humans, baby birds learn to vocalize by listening to adults.

songbirds learn to sing: By Carol Clark, Scientists studying how songbirds stay on key have developed a statistical explanation for why some things are harder for the brain to learn than others. “We’ve built the first mathematical model that uses a bird’s previous sensorimotor experience to predict its ability to learn,” says Emory biologist Samuel Sober. “We hope it will help us understand the math of learning in other species, including humans.” Sober conducted the research with physiologist Michael Brainard of the University of California, San Francisco. Their results, showing that adult birds correct small errors in their songs more rapidly and robustly than large errors, were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Sober’s lab uses Bengalese finches as a model for researching the mechanisms of how the brain learns to correct vocal mistakes. Just like humans, baby birds learn to vocalize by listening to adults. Days after hatching,

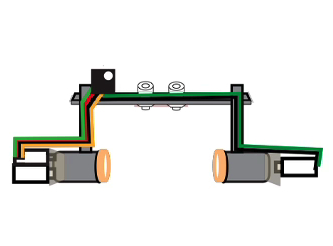

A Bengalese finch outfitted with headphones. Research on how the birds learn to sing may lead to better human therapies for vocal rehabilitation.

Bengalese finches start imitating the sounds of adults. “At first, their song is extremely variable and disorganized,” Sober Young birds, and young humans, make a lot of big mistakes as they learn to vocalize. As birds and humans get older, the variability of mistakes shrinks. One theory contends that adult brains tend to screen out big mistakes and pay more attention to smaller ones. “To correct any mistake, the brain has to rely on the senses,” Sober explains. “The problem is, the senses are unreliable. If there is noise in the environment, for example, the brain may think it misheard and ignore the sensory experience.” The link between variability and learning may explain why youngsters tend to learn faster and why adults are more resistant to change. “Whether you are an opera singer or a bird, there is always variability in your sounds,”

known as a parakeet in America), was accepted into the 1995 Guinness Book of World Records as "the bird with the largest vocabulary in the world." He was acknowledged as having 1,728 wordswhen the Guinness Book went to press. The documentation for his feat took place over a six-month period when 21 volunteer observers in 21 separate sessions took notes on what they heard Puck say. Several observers were members of the Redwood Empire Cage Bird Club (Sonoma County, California), and most were familiar with various species of parrots. Two of the volunteers were avian veterinarians. In addition to the volunteer observations, tape recordings and a video were provided as documentation for Guinness. Puck's owner/caregiver, Camille Jordan, of Petaluma, California has about 30 hours of Puck tape recordings, videos and detailed records of every word she heard spoken! Puck appeared on several Bay Area newscasts in December 1991 after an article was written about him in American

Cage-Bird Magazine. Another article about Puck appeared in Bird World (Vol. 15, No. 6, 1994). Rather than just mimicking, Puck created his own phrases and sentences. He often used the appropriate phrase in a situation, and sometimes displayed an uncanny understanding of his environment. For example, on Christmas morning, 1993 Puck was entertaining himself on the coffee table in the living room when Camille and her husband heard him say: "It's Christmas. That's what's happening. That's what it's all about. I love Pucky. I love everyone." Unfortunately, Puck's life was too brief. He was only five years old when he died of a gonadal tumor on August 25th, 1994(rip). He had been accepted into the Guinness Book only a few months earlier. Puck appeared in the 1995-8 Guinness Books, was omitted from the 1999-2002 editions and reappeared in the 2003-4 editions. The 2005 paperback Guinness Book has not been released at the time of this writing. Readers should note that record holders will not necessarily appear in every Guinness Book!" Source: Article. Birds and babies learn to  ‘talk’ similarly: study: Scientists have found compelling evidence that birds and human infants learn to string syllables together in roughly the same way: through stepwise improvement. A team of researchers from Japan, Israel and the US has described how they taught songbirds to sing a new tune and compared an analysis of the results with sounds made by human infants saved in a database. The process that allows humans to learn to talk as they move through various stages of development has been a research focus. Source: Article, Image. Amazing Talking Birds: Some people want a pet so they can exercise and play with, Still other people

want a companion -- an animal that will be an unquestioning, faithful through thick and thin. That's all good for them, but there are those of us who want a companion that we can talk to. We want a voice at the end of a long work day welcoming us home with, "Hello, darling, how was your day?" For people who wish to have that type of companion in the form of an animal, a talking bird fits the bill very nicely. However, not just any talking bird will do. Some birds speak quietly, while others will scream at the top of their lungs. The type of bird one chooses must be paired suitably with the environment in which one lives. That is, house or apartment, metropolitan or suburban. At any time of day. But, perhaps you live in the countryside and the only audio comfort that needs to be taken into consideration is your own. In that case, you will need to decide how much noise you can handle through the day. All talking birds are great fun to have as companions, but some are better at verbalizing and enunciating their words than others. Some species have better memory than others and are able to store hundreds, even thousands of words into their little bird brains. Then there are the select few, like the African Grey, that are able to listen to people talk, discern the proper context and situation, and hold a reasonable conversation (reasonable within the context of being a bird). There are even birds that will break out of their norm and surprise everyone with its highly capable memory and language skills. It is those bizarre birds that are often showcased on shows like Animal Planet. For this list, we based our picks on the special skills of species within the bird classes.

(9) Budgerigar — The budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus), also known as common pet parakeet or shell parakeet and informally nicknamed the budgie, is a small, long-tailed, seed-eating parrot. Their voice tends to be low and not always defined, and males tend to train better than females. Budgerigars are the only species in the Australian genus Melopsittacus, and are found wild throughout the drier parts of Australia where the species has survived harsh inland conditions for the last five million years.Budgerigars are naturally green and yellow with black, scalloped markings on the nape, back, and wings, but have been bred in captivity with colouring in blues, whites, yellows, greys, and even with small crests. Budgerigars are popular pets around the world due to their small size, low cost, and ability to mimic human speech. The origin of the budgerigar's name is unclear. The species was first recorded in 1805, and today is the most popular pet in the world after the domesticated dog and cat. The budgerigar is closely related to the lories and the fig parrots. They are one of the parakeet species, a non-taxonomical term that refers to any of a number of small parrots with long, flat and tapered tails. In both captivity and the wild, budgerigars breed opportunistically and in pairs. Source: Article.  (8) Monk Parakeet — Also called the Quaker Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus), is a species of parrot, this colorful little bird is actually a small parrot. They are known for being very clever and social, developing large vocabularies of phrases and words. in most treatments the only member of the genus Myiopsitta. It originates from the temperate to subtropical areas of Argentina and the surrounding countries in South America. Self-sustaining feral populations occur in many places, mainly in North America and Europe. The nominate subspecies of this parakeet is 29 cm or 9 to 11 in long on average, with a 48 cm wingspan, and weighs 100 g. Females tend to be 10-20% but can only be reliably sexed by DNA blood or feather testing. it has bright green upperparts. The forehead and breast are pale grey with darker scalloping and the rest of the underparts are very-light green to yellow. smaller Source: Article  (7) Blue-Fronted Amazon — If you want a companion for life, this is a good fit. The Blue-Fronted can live for up to 100 years, or more. They have an excellent speaking voice, with a strong ability to mimic human voices. The Blue-fronted Amazon (Amazona aestiva), also called the Turquoise-fronted Amazon and Blue-fronted Parrot, is a South American species of Amazon parrot and one of the most common Amazon parrots kept in captivity as a pet or companion parrot. Its common name is derived from the distinctive blue marking on its head just above its beak. The Blue-fronted Amazon is a mainly green parrot about 38 cm (15 in) long. They have blue feathers on the forehead above the beak and yellow on the face and crown. Distribution of blue and yellow varies greatly among individuals. Unlike most other Amazona parrots, its beak is mostly black. There is no overt sexual dimorphism in plumage to the human eye, but analysis of the feathers using spectrometry, a method which allows the plumage to be seen as it would be by a parrot's tetrachromatic vision. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue-fronted_amazon  (6) Indian Ringneck — Very clever little birds, Indian Ringnecks (Psittacula krameri), also known as the Ring-necked Parakeet, can develop a large vocabulary, and speak very clearly in sentences. Not so much for mimicking the pitch of a human voice, they more often speak in their own bird voices, though they can carry the mood of the phrase. It is a gregarious tropical Afro-Asian parakeet species that has an extremely large range. Since the trend of the population appears to be increasing, the species was evaluated as Least Concern by International Union for Conservation of Nature in 2012. Rose-ringed parakeets are popular as pets. Its scientific name commemorates the Austrian naturalist Wilhelm Heinrich Kramer.This non-migrating species is one of few parrot species that have successfully adapted to living in 'disturbed habitats', and in that way withstood the onslaught of urbanisation & deforestation. In the wild, this is a noisy species with a sole crying call. Source: Link  (5) Eclectus —The Eclectus Parrot (Eclectus roratus) is a parrot native to the Solomon Islands, Sumba, New Guinea and nearby islands, northeastern Australia and the Maluku Islands (Moluccas). this parrot is able to verbalize distinctly and mimic the tone and mood of language. While its capabilities are strong, these abilities depend entirely on training from an early age. It is unusual in the parrot family for its extreme sexual dimorphism of the colours of the plumage; the male having a mostly bright emerald green plumage and the female a mostly bright red and purple/blue plumage. Joseph Forshaw, in his book Parrots of the World, noted that the first European ornithologists to see Eclectus Parrots thought they were of two distinct species. Large populations of this parrot remain, and they are sometimes considered pests for eating fruit off trees. Some populations restricted to relatively small islands are comparably rare. Their bright feathers are also used by native tribes people in New Guinea as decorations. The yellow-crowned amazon is found in the Amazon Basin and Guianas, with additional populations in north-western South America and Panama. Source: wikipedia.org/  (4) Yellow-Crowned Amazon — Considered to be nearly as good as the Yellow-Naped, with less of a tendency to nip. The Yellow-crowned Amazon or Yellow-crowned Parrot (Amazona ochrocephala), is a species of parrot, native to the tropical South America and Panama. The taxonomy is highly complex, and the Yellow-headed (A. oratrix) and Yellow-naped Amazon (A. auropalliata) are sometimes considered subspecies of the Yellow-crowned Amazon. have a total length of 33–38 cm (13–15 in). As most other Amazon parrots, it has a short squarish tail and a primarily green plumage. It has dark blue tips to the secondaries and primaries, and a red wing speculum, carpal edge (leading edge of the wing at the "shoulder") and base of the outer tail-feathers. The red and dark blue sections are often difficult to see when the bird is perched, while the red base of the outer tail-feathers only infrequently can be seen under normal viewing conditions in the wild. The amount of yellow to the head varies, with nominate, nattereri and panamensis having yellow restricted to the crown-region (occasionally with a few random feathers around the eyes, while the subspeciesxantholaema has most of the head yellow. All have a white eye-ring. They have a dark bill with a large horn or reddish spot on the upper mandible except panamensis, which has a horn coloured beak. Males & females do not differ in plumage. Except for the wing mirror, juveniles have little yellow & red to the plumage. Habitat and distribution: The yellow-crowned amazon is found in the Amazon Basin and Guianas, with additional populations in north-western South America and Panama. It is a bird of tropical forest (both humid and dry), woodland, mangroves, savanna and may also be found on cultivated land and suburban areas. In the southern part of its range, it is rarely found far from the Amazon Rainforest. It is mainly a lowland bird, but has locally been recorded up to 800 m (2600 ft) along on the eastern slopes of the Andes, Source: en.wikipedia.org  (3) Double Yellow Head Amazon — Closely following the Yellow-Naped, with an excellent ability to mimic human voices and a love for song The Yellow-headed Amazon (Amazona oratrix), also known as the Yellow-headed Parrot and Double Yellow-headed Amazon, is an endangered amazon parrot of Mexico and northern Central America. It prefers to live in mangrove forests or forests near rivers or other bodies of water. It is sometimes considered a subspecies of the Yellow-crowned Amazon. The Yellow-headed Amazon averages 38–43 centimetres (15–17 in) long. The shape is typical of amazons, with a robust build, rounded wings, and a square tail. The body is bright green, with yellow on the head, dark scallops on the neck, red at the bend of the wing, and yellow thighs. The flight feathers are blackish to bluish violet with a red patch on the outer secondaries. The base of the tail also has a red patch, which is usually hidden. The outer tail feathers have yellowish tips. The bill is horn-colored, darker in immatures of the Belizean subspecies. The eye ring is whitish in Mexican birds and grayish in others. The most conspicuous geographical difference is the amount of yellow. In adults, the head and upper chest are yellow in the subspecies of the Tres Marías Islands (tresmariae); just the head in the widespread subspecies of Mexico (oratrix); just the crown in Belize (belizensis); & the crown and nape in the Sula Valley of Honduras (hondurensis, which thus Matches the Yellow-naped Parrot). Immatures have less yellow than adults; join adult plumage in 2 to 4 years. Source: en.wikipedia.org Spotted Wood Kingfisher

(2) Hill Myna — This pretty little black bird has an amazing capacity for mimicking human voices, with a varied range of pitch and tonality. The common hill myna (Gracula religiosa), sometimes spelled "mynah" and formerly simply known as hill myna, is the myna bird most commonly seen in aviculture, where it is often simply referred to by the latter two names. It is a member of the starling family (Sturnidae), resident in hill regions of South Asia and Southeast Asia. The Sri Lanka hill myna, a former subspecies of G. religiosa, is generally accepted as a separate species G. ptilogenys nowadays. The Enggano hill myna (G. enganensis) and Nias hill myna (G. robusta) are also widely accepted as specifically distinct, and many authors favor treating the southern hill myna (G. r. indica) from the Nilgiris and elsewhere in the Western Ghats of India as a separate species, also. Source: Article

(1) African Grey — The African Grey is widely considered to be the smartest of the talking birds, and one of the most intelligent in the animal kingdom overall. Some experts say they approach the ability to speak and relate concepts on the level of a human toddler. Of the two standard "domesticated" species, the Timneh African Grey tends to learn to speak at a younger age than the Congo African Grey. The African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus), also known as the Grey Parrot, is a parrot found in the primary and secondary rainforest of West and Central Africa. Experts regard it as one of the most intelligent birds in the world. They feed primarily on palm nuts, seeds, fruits, and leafy matter, but have also been observed eating snails. Their overall gentle nature and their inclination and ability to mimic speech have made them popular pets, which has led many to be captured from the wild and sold into the pet trade. The African Grey Parrot is listed on CITES appendix II, which restricts trade of wild-caught species because wild populations cannot sustain trapping for the pet trade. Source: Articl-1-2, Image: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10. Parrot who speaks Urdu & English: Mittu the parrot deserves congratulations – or as the  African grey might say, ‘shabaash’, Daily Mail online reports. The bilingual bird has developed an impressive vocabulary in both English and Urdu after being raised in a home where both are spoken.As well as the likes of ‘who’s a pretty boy then’, the two-year-old has mastered the traditional Muslim greeting ‘Asalaam Alaykum’ and ‘Bismillah’, the Urdu for ‘in the name of Allah’. Owner Ghaffar Ahmed, 36, said: ‘He speaks Urdu and English. But he also barks like a dog and makes the noise of the refrigerator alarm, so he likes making all sorts of noises really.’ Mittu lives with Ahmed’s family in Stourbridge, West Midlands. This year a study found that African greys are capable of the same level of intelligent reasoning as a four-year-old child. Ahmed said: ‘I don’t know how many bilingual birds there are in the UK but there can’t be many. ‘My in-laws live in Bradford and a family who they know were looking to re-home the parrot as he was becoming too much of a handful. ‘They wanted him to go to a home that spoke the same language, so we said we’d have him on board and ever since then he has become part of the family. Ahmed, who runs a car firm and accident management company, says he is refusing to take him out to the local mosque – after the parrot escaped recently from his workplace. Ahmed, his wife, Shabana, 31, and their three young daughters were ‘devastated’ when he disappeared. But tears turned to joy when the bird turned up four days later having flown four miles away. Susan Lane, from Halesowen, West Midlands, found the Mittu in her holly tree and found Ahmed online. ‘As soon as we were reunited he came and kissed my face,’ Ahmed added. ‘We were delighted to have him back, it was like losing one of the family when he flew off. ‘So I’m not letting him go out any more, I’m keeping a close eye on him from now on.’ daily times monitor. Source: Article, Image. What is a Mockingbird?: They are members of the Mimidae family, a group of American

passerines that also includes thrashers, tremblers, and New World catbirds. These stentorian songbirds, medium sized with angular proportions and long, twitchy tails, range from the Canadian border down through South America. The Northern Mockingbird, the most well known representative of this family above the equator, is

"Mimus polyglottos adult 02 cropped" by Captain-tucker - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

Northern Mockingbird by Mike, found fittingly at Hotel Mocking Bird Hill in Jamaica

known scientifically as Mimus polyglottos, which comes from the Greek “mimus” to mimic, and “ployglottos” for many-tongued. The song of the mockingbird is actually a medley of the calls of many other birds. Each imitation is repeated two or three times before another song is initiated. A given bird may have 30, 40 or even 200 songs in its

repertoire, including other bird songs, insect and amphibian sounds, and even the occasional mechanical noise. Part of the mockingbird’s advantage over other avians is physical; it uses more of the muscles in its vocal organ, the syrinx, than most other passerines do, many more than non-passerines like raptors or waterfowl. But the mockingbird also has a mind for music. It’s been theorized that this species has more brain matter devoted to song memory than most other birds do. Why does the mockingbird sing? The vocal mimicry trait seems to indicate that lyrical flow is an

"Galapagosmockingbird-santa-fe-island" by Benjamint444 - Own work. Licensed under GFDL 1.2 via Commons.

especially potent aphrodisiac in mockingbird circles, although some lonely males warble and whine the whole night through when unable to find a mate. “Northern” is a rather ambiguous descriptor for Mimus polyglottos, as it is the only mockingbird to appear regularly anywhere north of Mexico. The Northern Mockingbird, clad in shades of gray with conspicuous white wing patches, enjoys exceptional popularity for such a drab specimen, evident in the fact that it is the state bird of Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee and Texas. Other Mimus species mockingbirds, 9 in all, closely resemble the Northern Mockingbird, which, in my experience, is more common in the Bahamas than the Bahama Mockingbird (M. gundlachii) and may even appear in the tropics alongside

"Mimus polyglottos1" by Ryan Hagerty - This image originates from the National Digital Library of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. See Category:Images from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

the Tropical Mockingbird (M. gilvus). No wonder it’s so popular! Birds of the genus Nesomimus are known as the Galapagos mockingbirds. These 4 species endemic to the celebrated archipelago, Galapagos (N. parvulus), Floreana (N. trifasciatus), Espanola (N. macdonaldi), andSan Cristobal (N. melanotis), are said to have been extremely influential in shaping Darwin’s theories on the origins of life. Tragically, the critically endangered Floreana mockingbird is extinct on the island for which it is named. The only Mimodes mockingbird, the Socorro Mockingbird (M. graysoni), endemic to

Socorro Island in the Revillagigedo Islands, is also endangered. Species in the genus Melanotis certainly live up to their billing as the blue mockingbirds. The Blue (M. caerulescens) and Blue-and-white (M. hypoleucus), found in Mexico and Central America, both appear exquisitely azure, a dramatic departure from the family’s typical ashen hues. It’s considered a sin to kill a mockingbird, or at least that’s what we’re told in the book of the same name. Why? As Harper Lee says, “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” Source: Article. Oh! my feathered friend: People have kept birds as pets for centuries. They have been admired for their companionship and even ornamental value. However, some birds, such as parrots and cockatoos are very intelligent and intuitive as well. When it comes to bringing a bird home, it's important to realise that it requires a commitment that is unparalleled by any other. Exotic birds such as a Cockatoo or Macaw lives up to an age of 50-60 years. Even an ordinary parakeet lives up to 20 years. Exotic birds are the most sought after feathered pets in India. By “exotic” we mean, birds that are not native to India. These include; the African Love Birds, Zebra Finches, Java Sparrows and Budgerigars — commonly known as Lovebirds. Abdul Wahab of the Bengaluru-based Wet Pets, breeds a variety of exotic birds. He says, “Lovebirds are the world’s favourite birds for keeping as pets. Exotic birds arrived in India years ago, brought in by the British, merchants and travellers, from places as far flung as the Amazon, Africa, South America and Australia. Since then they have been bred in captivity in India and have acclimatised to the weather here.” While Cockatoos and Zebra Finches are native to Australia, the Grey Parrot and Yellow Naped Parrot belong to the Amazon. The majestic Macaw comes from South America. “Cockatoos, Macaws and Grey Parrots make great companions, and if brought home as a chick, develops a great bond with the owner.” Sahil Ismail, of the Pune-based Creekwood Birds, has been breeding and keeping birds since the age of ten. Today, Sahil is one of the country’s best known aviculturists with a wide collection of exotic birds. “Keeping birds is relatively easy as they require dry food that comprises of fresh fruit and a mixture of seeds. It is important to constantly supply them with fresh water.” He adds, “In my experience, I’ve found that the African birds are comparatively fragile, while the South African ones are hardy.” Anna Verghese, who’s kept a number of birds as pets at home, comments, “Birds are certainly not as demanding as dogs or cats. They require their nails to be trimmed regularly — so that they don’t scratch us. Also, their feathers need to be clipped as they can’t survive in the wild.” Source: Article. Birds That Live With Varying Weather Sing More Versatile Songs: A new study of

Credit: Wikipedia

North American songbirds reveals that birds that live with fluctuating weather are more flexible singers. Mixing it up helps birds ensure that their songs are heard no matter what the habitat, say researchers at Australian National University and the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center. To test the idea, the researchers analyzed song recordings from more than 400 male birds spanning 44 species of North American songbirds — a data set that included orioles, blackbirds, warblers, sparrows, cardinals, finches, chickadees and thrushes. They used computer software to convert each sound recording — a medley of whistles, warbles, cheeps, chirps, trills and twitters — into a spectrogram, or sound graph. Like a musical score, the complex pattern of lines and streaks in a spectrogram enable scientists to see and visually analyze each snippet of sound. For each bird in their data set, they measured song characteristics such as length, highest and lowest notes, number of notes, and the spacing between them. When they combined this data with temperature and precipitation records and other information such as habitat and latitude, they found a surprising pattern — males that experience more dramatic seasonal swings between wet and dry sing more variable songs. "They may sing certain notes really low, or really high, or they may adjust the loudness or tempo," said co-author Clinton Francis of the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center. The Pyrrhuloxia or desert cardinal from the American southwest and northern Mexico and Lawrence's goldfinch from California are two examples. In addition to variation in weather across the seasons, the researchers also looked at geographic variation and found a similar pattern. Namely, species that experience more extreme differences in precipitation from one location to the next across their range sing more complex tunes. House finches and plumbeous vireos are two examples, Francis said. Why might this be? "Precipitation is closely related to how densely vegetated the habitat is," said co-author Iliana Medina of Australian National University. Changing vegetation means changing acoustic conditions. "Sound transmits differently through different vegetation types," Francis explained. "Often when birds arrive at their breeding grounds in the spring, for example, there are hardly any leaves on the trees. Over the course of just a couple of weeks, the sound transmission changes drastically as the leaves come in." "Birds that have more flexibility in their songs may be better able to cope with the different acoustic environments they experience throughout the year," Medina added. A separate team reported similar links between environment and birdsong in mockingbirds in 2009, but this is the first study to show that the pattern holds up across dozens of species. Interestingly, Francis and Medina found that species with striking color differences between males and females also sing more variable songs, which means that environmental variation isn't the only factor, the researchers say. The team's findings were published online in the August 1, 2012 issue of the journal Biology Letters. Contacts and sources: Robin Ann Smith, National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent), Citation: Medina, I. and C. Francis (2012). "Environmental variability and acoustic signals: a multilevel approach in songbirds." Biology Letters. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0522, The National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent) is a nonprofit science center dedicated to cross-disciplinary research in evolution. Funded by the National Science Foundation, NESCent is jointly operated by Duke University, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and North Carolina State University. For more information about research and training opportunities at NESCent, visit www.nescent.org. Source: Nano Patents And Innovations, Animals Know What They Are Talking About: African Grey Parrot Has Social Skills of 2 Year Old and

"Psittacus erithacus timneh-parrot on cage" by Peter Fuchs - Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons.

Intelligence of 5 Year Old Child: These bird brains are proving to be smarter than we thought When African Grey parrots talk, do they mimic sounds or consciously understand their speech? Irene Pepperberg, a comparative psychologist at both Brandeis and Harvard universities believes African Greys actually know what they’re talking about. "They understand things like categories of color, material and shape, number concepts, and concepts of bigger and smaller, concepts of similarity and difference, and absence; things we once thought that a bird could not comprehend, these parrots are showing us it's possible," says Pepperberg. With support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Pepperberg studies the cognitive and communicative abilities of African Greys. She says the birds have the social skills of a 2-year-old child and the intelligence of a 5-year-old. That statement might ruffle some feathers, but in Pepperberg's lab at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., she's out to prove that talking with the animals isn't just the stuff of fiction. To start, talking with these birds means simplifying language down to "motherese." Instead of asking what something is made of, Pepperberg will ask, "What matter?" And, when she asks the bird "What shape?" instead of saying "square," they say "four-corner," to clarify the relationship between shape and numbers of points on an object. One of the things Pepperberg studies is the parrots' ability to identify partially obscured shapes. "In the wild, we expect these birds to be able to do that because if you see part of a predator, you want to respond as if it is an entire predator," says Pepperberg. She demonstrates this by showing a parrot a square, partially obscured by a circle, and the bird is still able to identify the shape as "four-corner." If the parrot responds to "What shape?" by just saying "corner," Pepperberg asks "How many corners?" and the parrot responds "four." The bird doesn't get it right 100 percent of the time, but Pepperberg's data suggests they understand the concept of a square even when it is partially obscured. When testing, Pepperberg is cautious, making sure she doesn't send subtle cues to the birds. "We have controlled for that many times," she explains. "We have different people training versus testing. We mix up different types of questions in each test session. The testing is basically blind." Pepperberg says her research on talking with birds has benefits for humans. "A colleague has used our training techniques--a two-person modeling system--with autistic children to help them learn speech and communication skills," she says. Pepperberg believes that despite the birds having a brain the size of a shelled walnut, their contribution to understanding language and intelligence is significant. "All of our work is trying to show people that 'birdbrain' should really be a compliment," she adds. Contacts and sources: National Science Foundation, Miles O'Brien, Science Nation Correspondent, Jon Baime, Science Nation Producer. Source: Article, Image

Aggressive

In any case, the image of a bird generally doesn’t produce anything terrifying. However, not all birds are cute, and not all of them are nice, so to speak. There are hundreds of birds that could attack a human, and do a lot of damage. Here is a list of nine most dangerous bird. 1. Cassowaries Cassowaries, an endangered species, are  large, flightless birds that live in the rainforests, woodlands and swamps of Australia. Cassowaries are unpredictable, aggressive and are known to kick up their large, clawed feet. Their kicks are capable of breaking bones, and their claws have been likened to daggers. 2. Ostriches: Ostriches are suspicious, skittish and can be dangerous.  They're the largest living bird (they can reach over 9 feet tall and 350 pounds) and they can outrun you (a steady 30 miles an hour for 10 miles straight). Like the cassowary, they have strong legs (their kick can kill a hyena) and sharp claws. 3. Canada Geese: Canada geese are very aggressive and, particularly if you (purposely  or inadvertently) come near their nests or young, they may chase you away and even bite you. 4. Seagulls: Seagulls are extremely aggressive and are known to attack and even peck at people's heads to protect their nests and young. In fact, in Britain people have been forced to carry umbrellas to avoid the attacks, at least one  woman was taken to an emergency room with deep beak wounds to her head, and a pet dog was killed by the birds. 5. Owls: Owls are raptors, or birds of prey, and they use their talons and beaks to kill and eat their catch. In a closed space, or if the bird  was scared or agitated, it could cause serious harm to you. 6. Hawks and Falcons: Also birds of prey, the sharp talons and beaks that hawks and falcons use to hunt, along with their quick speed and agility, pose serious dangers to humans, even if  the birds are just babies (falcons' beaks are also specially configured to cut through the spinal cords of their prey). 7. Eagles: Eagles are strong (strong enough to carry away something that weighs four pounds), aggressive birds, and although they don't pose  much of a danger to humans in the wild, in a closed space their beak and talons could easily harm a human. (FYI, they can eat about a pound of fish in just four minutes.) 8. Vultures: If cornered, a vulture (many species of which are now endangered) may  hiss or make a low grunting sound at you. They, of course, also have sharp, hooked beaks that can tear meat, along with excellent eyesight. 9. Rheas: The rhea, native to South America, is a large, flightless bird that can grow to be 60-80 pounds. Though  smaller than ostriches and not as aggressive as cassowaries, rheas have heavily muscled legs, hard spurs on their feet and their kicks can bring a force of 800 pounds per square inch. Source: Article. Golden Eagle tries to snatch kid in

Golden Eagle is moving towards kids (Image: Screen shot on below video)

Montreal: A child flees from what could have been a disaster, as he is clutched by a Golden Eagle, while sitting in a park in Montreal, Canada. You can observe as the eagle moves towards the baby, and the father is filming the whole event. As he perceives the bird start to veer down, and skull it for his people, he frights and jogs towards it. The infant is raised in the air for a few moments, but it emerges the eagle lets go soon after. Many are claiming this video is a fake, as the father's reaction seems to be too detached and a little late. After all, he stops to admire the bird instead of running to protect his family as he sees it approach them. If you didn't catch the sequence, it is

played in small motion at the end of the clip. According to wikipedia The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is one of the best-known birds of prey in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. Once widespread across the Holarctic, it has disappeared from many areas which are now more heavily populated by humans. Despite being extirpated from or uncommon in some its former range, the species is still fairly ubiquitous, being present in sizeable stretches of Eurasia, North America,

and parts of North Africa. It is largest and least populous of the mere 5e species of true accipitrid to occur as a breeding species in both the Palearctic and the Nearctic, alongside the Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), the Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus), the Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the Rough-legged Buzzard (Buteo lagopus). The Golden Eagle is one of the most extensively studied species of raptor in the world in some parts of its range, such as the Western United States and the Western Palearctic (especially Scotland,Scandinavia and Spain). However in many other parts of its range, especially in Asia (outside of Japan) and Russia, the life histories of Golden Eagles are mostly unknown. In the Middle East, the Caucasus, North Africa and even the Eastern United States and Eastern Canada, they are relatively poorly known, though the number of studies in these areas have recently increased. These birds are dark brown, with lighter golden-brown plumage on their napes. Immature eagles of this species typically have white on the tail and often have white markings on the wings. Golden Eagles use their agility and speed combined with extremely powerful feet and massive, sharp talons to snatch up a variety of prey. The most prevalent prey are hares, rabbits, marmots and other ground

squirrels. Exceptionally large, such as foxes and young ungulates, and small mammals, such as shrews and mice, can turn up in the diet as well. Birds, including large species up to the size of swans and cranes, have also been recorded as prey. Certainly, the preferred avian prey would be the galliforms. They will occasionally eat carrion, as well as reptiles, amphibians and even insects. For centuries, this species has been one of the most highly regarded birds used in falconry, with the Eurasian subspecies having been used to hunt and kill unnatural, dangerous prey such as Gray Wolves (Canis lupus) in some native communities. Due to their hunting prowess, the Golden Eagle is regarded with great mystic reverence in some ancient, tribal cultures. Unfortunately, the same boldness and power that led to them being held with reverence in early cultures has led to wholesale persecution in the last few centuries, due to the perceived (and often greatly exaggerated) threat Golden Eagles pose to domestic and game stock. Golden Eagles maintain home ranges or territories that may be as large as 200

"Eagle and Lamb - James Audubon" by James Audubon - http://ia351434.us.archive.org. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

also have their iconic symbols that can range from buildings to geological formations to plants and animals. For the United States, it is the bald eagle - a symbol of magnificence and strength. And as the American expansion rolled across the great nation, the bald eagle, whether deliberately or by accident, was slowly pressured and pushed from one habitat to another until this iconic symbol of one of the most powerful and successful nations on earth was faced with extinction. Irony abounds. Chosen as the national bird in 1782 (to the disappointment of statesman Benjamin Franklin who had proposed the turkey), the bald eagle's numbers slowly declined until there were only 417 nesting pairs of eagles in the lower 48 states when the Endangered Species Act was initiated in 1963 (the bald eagle was formally declared endangered under the Act in 1967). The nation's founding fathers did not have to travel far within the new fledgling states to see a bald eagle, but by the 20th century the birds were typically found only in rugged, remote mountainous areas - further west and north where human populations were scarce as was large scale agriculture. Along with large commercial agriculture came the need to control pests and with that came the use of pesticides. The broad use of DDT contributed to the decline of the bald eagle - as well as many other birds of prey - as the pesticide slowly worked its way

up the food chain. When ingested by bald eagles, it produced weakened eggs and the bird's survival rate plummeted. Midwest states, with large population centers and agriculture, were essentially devoid of bald eagles. The state of Iowa, as an example, did not have a single nest from the early 1900s until the late 70s when one nest was finally sighted. But now it appears that is all changing. Iowa's number of nesting pairs numbered around 9,000 in 2006 and they continue to grow. With the use of DDT discontinued, along with the adoption of other regulatory measures between the United States and Canada, the overall population of bald eagles has continued to rise and it was officially de-listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1997. Numbers now range over 115,000 in the United States and Canada. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources carefully monitors the number of nests and nesting pairs, utilizing a program that involves both government officials and volunteers to monitor the nests. The birds need to be observed but not disturbed in any way, so involved conservation groups and the department keep the exact location of many of the nests under wraps. The return of bald eagles to states like Iowa is an example of the overall success nationwide in bringing back the populations of bald eagles back to respectable levels. It is the iconic symbol of a nation but, more importantly, it is an important member of nature's balanced community and a success story that bears repeating for many animal and plant species from coast to coast. The Republic, Source: Wikipedia, Article, Scientists Show Dinosaur Body Shape Changed The Way

Credit: University of Liverpool

Birds Stand: Scientists at the University of Liverpool and the Royal Veterinary College developed computer models of the skeletons of dinosaurs to show how body shape changed during dinosaur evolution and affected the way birds stand today. The study reveals for the first time that, contrary to popular opinion, it was the enlargement of the forelimbs over time, rather than the shortening and lightening of the tail, that led to two-legged dinosaurs gradually adopting an unusually crouched posture, with the thigh held nearly horizontally – a trait inherited by their descendants: birds. The research group used digitising technology to create 3D images of the skeletons of 17 archosaurs – land animals including living crocodiles and birds as well as extinct dinosaurs. They then digitally added ‘flesh’ around the skeletons to estimate the overall shape of the body as well as the individual body segments such as the head, forelimbs and tail. Evolution: Dr Karl Bates, from the University’s Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, said: “The evolution of birds from their dinosaurian ancestors is historically important not only to dinosaur research but also to the development of the theory of evolution itself. “Way back in the 1860’s, Thomas Huxley used Mesozoic dinosaurs and modern birds as key evidence in promoting Darwin’s theory of evolution. In this study, modern digital technologies have allowed us to quantify the ‘descent with modification’ observed by Huxley all those years ago. “This quantifiable evidence, derived from fossils, helps make evolution more apparent to a general audience, and helps demonstrate exactly how scientists understand what they do know about evolution.” Dr Vivian Allen, from the Royal Veterinary College, said: “We started from a simple digital ‘shrink-wrap’ of the whole skeleton. From this, we expanded the ‘shrink-wrap’ to match how much flesh we think existed around the different parts of the skeleton. This was based on both detailed reconstruction of the muscular anatomy of each animal, and on what we have measured from CT scans of their living relatives.” Prior research had shown that the first archosaurs, around 245 million years ago, were superficially like modern crocodiles – four-legged animals with long, heavy tails, although with longer limbs for living and moving on land. However, early in the evolution of the dinosaur lineage, about 235 million years ago, dinosaurs became bipedal, a trait inherited by their descendants – birds. Birds stand and walk in an unusually crouched posture, with the thigh held nearly horizontally. Palaeontologists had agreed for years that this strange way of moving evolved gradually as the tail became shorter, shifting the centre of mass of certain dinosaurs progressively forward as those dinosaurs became more “bird-like”, and thereby requiring the legs to become less vertical and more crouched to keep the centre of mass balanced over the feet. A major, unexpected implication of the team’s discovery is that, due to the effects on centre of mass position on leg posture, forelimb size and leg function are biomechanically linked. So, these changes in the forelimb anatomy of dinosaurs, both before and after flight, also altered the way they stood, walked and ran. The study was supported by funds from the Natural Environment Research Council and the Royal Society. Contacts and sources: University of Liverpool, Source: Article. Red-Tailed Hawk: predatory birds are ever-present & vital to nature's balance: Predators play an important role in maintaining balance within nature's ecosystems. When we think of a predator, we often think of large animals like sharks, lions, or wolves. But predators come in all sizes. In  fact, any animal that feeds on another animal can be considered a predator and that predation helps to keep the populations of its prey healthy by weeding out the sick or aged, and keeping numbers in check by counteracting high reproductive rates. In fact, for animals that are prey to several different kinds of predators, a high reproductive rate is nature's consolation prize of sorts for being the unwitting prize of a predator. In the seas, plankton, krill and many species of small bait-fish have high reproductive rates as they are a food source for many different predator species ranging from small reef fish to massive whales. And on land, many rodent species - rats and mice in particular - reproduce in great numbers to offset predation from everything from coyotes to hawks. Speaking of predatory birds, their roles are very similar to predators like sharks. Two roles actually, depending on the bird. Sharks play a critical role as scavengers and there are vultures and buzzards that play a similar role. Sharks are also hunters and hawks and eagles follow parallel duties. To hunt, the predator needs an advantage and for hawks it can often be incredibly sharp eyesight combined with lightning speed. Source: Article. Hawks, eagles, attack US Army's new realistic robotic bird drone: Washington: A robotic bird created for the US fact, any animal that feeds on another animal can be considered a predator and that predation helps to keep the populations of its prey healthy by weeding out the sick or aged, and keeping numbers in check by counteracting high reproductive rates. In fact, for animals that are prey to several different kinds of predators, a high reproductive rate is nature's consolation prize of sorts for being the unwitting prize of a predator. In the seas, plankton, krill and many species of small bait-fish have high reproductive rates as they are a food source for many different predator species ranging from small reef fish to massive whales. And on land, many rodent species - rats and mice in particular - reproduce in great numbers to offset predation from everything from coyotes to hawks. Speaking of predatory birds, their roles are very similar to predators like sharks. Two roles actually, depending on the bird. Sharks play a critical role as scavengers and there are vultures and buzzards that play a similar role. Sharks are also hunters and hawks and eagles follow parallel duties. To hunt, the predator needs an advantage and for hawks it can often be incredibly sharp eyesight combined with lightning speed. Source: Article. Hawks, eagles, attack US Army's new realistic robotic bird drone: Washington: A robotic bird created for the USArmy for being used as a miniature spy drone is so convincing that it has been attacked by hawks and eagles, according to researchers. The solar-powered, remotely piloted surveillance aircraft, called Robo-Raven, was designed and built at the University of Maryland's Maryland Robotics Center, reports the Washington Times. John Gerdes, a mechanical engineer with the Vehicle Technology Directorate at the US Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, said that the Robo-Raven already attracts attention from birds in the area which tends to hide its presence. Seagulls, songbirds and sometimes crows tend to try to fly in formation with the robotic bird during testing, but birds of prey, such as falcons and hawks, take a much more aggressive approach, he said. The Robo-Raven's wings flap completely independently of each other and can be programmed to perform any desired motion, enabling the bird to carry out aerobatic flight maneuvers, such as diving and rolling, never before possible, Gerdes said. (ANI). Source: Article.

Speed

Hickman Students use a special high-speed camera to discover new, never-before-seen intricacies of flight and slow motion video to analyze flight parameters for future applications. "The best way to prevent a small drone from spying on you in your office is to turn on the air-conditioning," said David Lentink, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford. That little blast of air, he explained, creates enough turbulence to knock a hand-size UAV off balance, and possibly send it crashing to the floor. A pigeon, on the other hand, can swoop down busy city streets, navigate around pedestrians, sign posts and other birds, keep its path in all sorts of windy conditions, and deftly land on the tiniest of hard-to-reach perches. Graduate student Eirik Ravnan works with a parrotlet that he is training to fly from perch to perch in order to be filmed by a high-speed camera. "Wouldn't it be remarkable if a robot could do that?" Lentink wondered. If robots are to become a bigger presence in urban environments, they will need to. In order to build a robot that can fly as nimbly as a bird, Lentink began looking to nature. Using an ultra-high-speed Phantom camera that can shoot upwards of 3,300 frames per second at full resolution, and an amazing 650,000 at a tiny resolution, Lentink can visualize the biomechanical wonders of bird flight on an incredibly fine scale. Anna's hummingbirds, often spotted darting from flower to flower on the Stanford campus, beat their wings about 50 times per second, nothing but a green blur to human eyes. "Our camera shoots 100 times faster than humans' vision refresh rate," Lentink said. "We can spread a single wing beat across 40 frames, and see incredible things." First flight Every time Lentink's students take the camera into the field, they have the potential to make a groundbreaking discovery. Thousands of birds have never been filmed with a high-speed camera, their secret flight mechanics never exposed. Students Andreas Peña Doll and Rivers Ingersoll filmed hummingbirds performing a never-before-seen "shaking" behavior: As the bird dived off a branch, it wiggled and twisted its body along its spine, the same way a wet dog would try to dry off. At 55 times per second, hummingbirds have the fastest body shake among vertebrates on the planet – almost twice as fast as a mouse. The shake lasted only a fraction of a second, and would never have been seen without the aid of the high-speed video. "We're actually in a position where we can quantitatively analyze this video, and some of the results are the first results of their kind," said Ingersoll, an engineering graduate student who specializes in hummingbird flight. "It is kind of cool to know that potentially other researchers in the future will look at the data we've got in this class and [it will] help them with their research." Though Lentink's lab has amassed hours of short clips of bird flight, it's difficult to frame up a perfect shot in the wild, so his students supplement this footage with carefully orchestrated laboratory-based experiments. "In the field, you can observe social interactions near other birds, how they fly through the wind or through clutter," Lentink said. "This is very valuable. But the conditions aren't always ideal for examining discrete motions." Eirik Ravnan, a mechanical engineering graduate student, trains small birds called parrotlets to fly from perch to perch, or to fly through narrow passageways. In exchange for their flight displays, the birds receive their favorite seeds as a reward. Repeating and videotaping these actions in controlled conditions, he said, makes it possible to look more carefully at, for example, exactly how a bird tilts its wings to slow itself when landing, or how birds corner. The lab just acquired an advanced flow measurement system that can help elucidate how the birds manipulate the airflow with their wings during such maneuvers. "I've never even had a pet," Ravnan said. "But working with birds and investigating their flight mechanics and thinking about how to apply those abilities to robots has been a really interesting way to apply my studies in fluid dynamics." A better bird 'bot Search-and-rescue is one of the more attractive applications for robotic planes, particularly scanning a wide urban area for survivors after a natural disaster. The unpredictable environment will demand robots that can better deal with changing conditions. Mini-copters and planes often stall at steep angles, or when they get caught in a gust of wind. They have difficulty avoiding other airborne objects, and fly clumsily near buildings. Lentink and his students have already begun applying the lessons they've learned from birds to various robotic designs. "Hummingbirds are amazing at hovering, but it's not a very efficient form of flight," said Waylon Chen, a graduate student in Lentink's lab. "A swift flies a lot, so it has a very efficient wing platform, but its legs are too short to land. As we lay out the goal of our robotic design, we can pick and choose which natural mechanisms will be useful, and incorporate only those." This summer Lentink is making his camera and students available to local birders. (To apply, fill out this questionnaire. Email questions to birderquestionnaire@gmail.com) "We'd like to pair the camera with some bird enthusiasts who might know the natural history of these birds better than us," Lentink said. "We want to give people outside of Stanford the magical experience of using this camera, and hopefully learn something more about birds in the process." Contacts and sources: By Bjorn Carey, David Lentink, Mechanical Engineering, Dan Stober, Photo: L.A. Cicero, Stanford News Service, Source: Nano-Patents And Innovations. Pigeons use mental map to

"Canada-Goose-Szmurlo". Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Commons.

of the world but some of are better then all. Spine Tailed Swift: The White-throated Needletail (Hirundapus caudacutus), also known as Needle-tailed Swift or Spine-tailed Swift, is a large swift. It is the fastest-flying bird in flapping flight, with a confirmed maximum of 111.6 km/h (69.3 mph). It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 170 km/h (105 mph), though this has not been verified. These birds have very short legs which they use only for clinging to vertical surfaces. They build their nests in rock crevices in cliffs or hollow trees. They never settle voluntarily on the ground[citation needed] and spend most of their lives in the air, living on the insects they catch in their beaks. These swifts breed in rocky hills in central Asia and southern Siberia. This species is migratory, wintering south in the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Australia. It is a rare vagrant in western Europe, but has been recorded as far west as Norway, Sweden and Great Britain. In June 2013, the bird was spotted in the United Kingdom, the first sighting in 22 years. The bird flew into a wind turbine and died; its body was sent to a museum. The White-throated Needletail is a mid sized bird, similar in size to Alpine Swift, but a different build, with a heavier barrel-like body. They are black except for a white throat, white undertail, which extends on to the flanks, and a somewhat paler brown back. The Hirundapus needletailed swifts get their name from the spiny end to the tail, which is not forked as in the Apus typical swifts. Source: Article. Frigate Bird: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up

"Fregata magnificens -Galapagos, Ecuador -male-8 (1)" by Andrew Turner from Washington, DC, United States - Frigate Bird Uploaded by

to 153 km/h , They are found mostly in North American and Central American countries. The frigatebirds are a family, Fregatidae, of seabirds. There are five species in the single genus Fregata. They are also sometimes called Man of War birds or Pirate birds. Since they are related to the pelicans, the term "frigate pelican" is also a name applied to them. They have long wings, tails, and bills and the males have a red gular pouch that is inflated during the breeding season to attract a mate. Frigatebirds are pelagic piscivores that obtain most of their food on the wing. A small amount of their diet is obtained by robbing other seabirds, a behaviour that has given the family its name, and by snatching seabird chicks. Frigatebirds are seasonally monogamous, and nest colonially. A rough nest is constructed in low trees or on the ground on remote islands. A single is laid each breeding season. The duration of parental care in frigatebirds is the longest of any bird. [citation needed]. Spur Winged Goose: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 142 km/h ,

"Spur-winged Goose RWD4" by Dick Daniels (http://carolinabirds.org/) - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

Spur Winged Goose is the worlds third fastest flying bird. It can fly 142 kilometers per hour. The Spur-winged Goose (Plectropterus gambensis) is a large bird in the family Anatidae, related to the geese and the shelducks, but distinct from both of these in a number of anatomical features, and therefore treated in its own subfamily, the Plectropterinae. It occurs in wetlands throughout sub-Saharan Africa.Adults are 75–115 cm (30–45 in) long and weigh on average 4–6.8 kg (8.8–15 lb), rarely up to 10 kg (22 lb), with males noticeably larger than the females. The wingspan can range from 150 to 200 cm (59 to 79 in). On average, the weight of males is around 6 kg (13 lb) and the weight of females is around 4.7 kg (10 lb). Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 42.5 to 55 cm (16.7 to 22 in), the bill is 5.7 to 6.4 cm (2.2 to 2.5 in) and the tarsus is 5.7 to 12 cm (2.2 to 4.7 in). They are the largest African waterfowl and are, on average, the world's largest wild "goose". They are mainly black, with a white face and large white wing patches. The long legs are flesh-coloured. The nominate race P. g. gambensis has extensive white on the belly and flanks, but the smaller-bodied subspecies P. g. niger, which occurs south of the Zambezi River, has only a small white belly patch. From a distance, P. g. niger can appear to be all black. The male differs from the female, not only in size, but also in having a larger red facial patch extending back from the red bill, and a knob at the base of the upper mandible. This is generally a quiet species. Typically, only males make a call, which consists of a soft bubbling cherwit when taking wing or alarmed. During breeding displays or in instances of alarm, both sexes may utter other inconspicuous calls Source: Article. Red-Breasted Merganser: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 142 km/h, The adult

Red-breasted Merganser is 51–62 cm (20–24 in) long with a 70–86 cm (28–34 in). It has a spiky crest and long thin red bill with serrated edges. The male has a dark head with a green sheen, a white neck with a rusty breast, a black back, and white underparts. Adult females have a rusty head and a greyish body. The juvenile is like the female, but lacks the white collar and has a smaller white wing patch. Source: Article. White Rumped Swift: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to

"Juvenile White-bellied Sea-eagle" by JJ Harrison (jjharrison89@facebook.com) - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

129 km/h, The White-rumped Swift (Apus caffer) is a small swift. Although this bird is superficially similar to a House Martin, it is not closely related to that passerine species. The resemblances between the swallows and swifts are due to convergent evolution reflecting similar life styles. Swifts have very short legs that they use only for clinging to vertical surfaces. They never settle voluntarily on the ground, and spend most of their lives in the air, feeding on insects that they catch in their beaks. They drink on the wing. White-rumped Swifts breed in much of sub-Saharan Africa, and have expanded into Morocco and southern Spain. The populations in Spain, Morocco and the south of Africa are migratory, although their wintering grounds are not definitively known. Birds in tropical Africa are resident apart from seasonal movements. This species appropriates the nests of little swifts and those swallows which build retort-shaped nests. In Europe and north Africa, this usually means the Red-rumped Swallow, but south of the Sahara other species like Wire-tailed Swallow are also parasitised. The original owners of the nests are driven away, or the white-rumps settle in the nest and refuse to move. Once occupied, the nest is lined with feathers and saliva, and one or two eggs are laid. The habitat of this species is dictated by that of its hosts, and is therefore normally man-made structures such as bridges and buildings. This 14-15.5 cm long species has, like its relatives, a short forked tail and long swept-back wings that resemble a crescent or a boomerang. It is entirely dark except for a pale throat patch and a narrow white rump. It is similar to the closely related Little Swift, but is slimmer, darker and has a more forked tail and a narrower white rump. Source: Article. Canvasback Duck: It is commonly reputed to reach

velocities of up to 124 km/h, The Canvasback (Aythya valisineria) is a species of diving duck, the largest found in North America. It ranges from 48–56 centimetres (19–22 in) in length and weighs 862–1,588 grams (1.90–3.50 lb), with a wingspan of 79–89 centimetres (31–35 in). The Canvasback has a distinctive wedge-shaped head and long graceful neck. The adult male (drake) has a black bill, a chestnut red head and neck, a black breast, a grayish back, black rump, and a blackish brown tail. The drake's sides, back, and belly are white with fine vermiculation resembling the weave of a canvas, which gave rise to the bird's common name.The bill is blackish and the legs and feet are bluish-gray. The iris is bright red in the spring, but duller in the winter. The adult female (hen) also has a black bill, a light brown head and neck, grading into a darker brown chest and foreback. The sides, flanks, and back are grayish brown. The bill is blackish and the legs and feet are bluish-gray. Its sloping profile distinguishes it from other ducks. Source: Article. Eider Duck: Eider Duck are found in the Northern

Hemisphere of the world. It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 113 km/h, . The Common Eider [pronunciation?] (Somateria mollissima) is a large (50–71 cm body length) sea-duck that is distributed over the northern coasts of Europe, North America and eastern Siberia. It breeds in Arctic and some northern temperate regions, but winters somewhat farther south in temperate zones, when it can form large flocks on coastal waters. It can fly at speeds up to 113 km/h (70 mph). The eider's nest is built close to the sea and is lined with the celebrated eiderdown, plucked from the female's breast. This soft and warm lining has long been harvested for filling pillows and quilts, but in more recent years has been largely replaced by down from domestic farm-geese and synthetic alternatives. Although eiderdown pillows or quilts are now a rarity, eiderdown harvesting continues and is sustainable, as it can be done after the ducklings leave the nest with no harm to the birds. Source: Article. Teal: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 109 km/h, The Eurasian Teal or

"Anas carolinensis (Green-winged Teal) male" by Jeslu - Flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Commons.

Common Teal (Anas crecca) is a common and widespread duck which breeds in temperate Eurasia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian Teal is often called simply the Teal due to being the only one of these small dabbling ducks in much of its range. The bird gives its name to the blue-green colour teal. It is a highly gregarious duck outside the breeding season and can form large flocks. It is commonly found in sheltered wetlands and feeds on seeds and aquatic invertebrates. The North American Green-winged Teal (A. carolinensis) was formerly (and sometimes is still) considered a subspecies ofA. crecca. The Eurasian Teal is the smallest extant dabbling duck at 34–43 cm (13–17 in) length and with an average weight of 360 g (13 oz) in drake (males) and 340 g (12 oz) in hens (females). The wings are 17.5–20.4 cm (6.9–8.0 in) long, yielding a wingspan of 53–59 cm (21–23 in). The bill measures 3.2–4 cm (1.3–1.6 in) in length, and the tarsus 2.8–3.4 cm (1.1–1.3 in). Source: Article. Mallard Duck: It is commonly reputed to reach velocities of up to 105 km/h..

The Mallard (ˈmælɑrd/ or /ˈmælərd/) or Wild Duck (Anas platyrhynchos) is a dabbling duck which breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand and Australia. This duck belongs to the subfamily Anatinae of the waterfowl family Anatidae. The male birds (drakes) have a glossy green head and are grey on wings and belly, while the females have mainly brown-speckled plumage. Mallards live in wetlands, eat water plants and small animals, and are gregarious. This species is the ancestor of most breeds of domestic ducks. Pintail Duck: Pintail Duck is also one of the sharpest bird

camera has helped show that the hummingbird is not only the fastest moving living thing on Earth but is also the fastest shaker. The camera, which is capable of capturing images at up to 650,000 frames per second, caught the birds shimmying at a rate that was 10 times faster than a dog after it takes a bath. Andreas Pena Doll and Rivers Ingersoll, both students in David Lentink's lab at Stanford University, captured Anna's hummingbirds shaking their tiny bodies 55 times per second while they were in flight, New Scientist reported. Lentink observed that it is the fastest shake by any vertebrate on Earth. Pena Doll said that the shimmy done in dry weather could remove pollen or dirt from their feathers similar to the way a wet shake removes water. The study will be published in the Journal for Biomechanics of Flight. (ANI). Source: Article.

Colorful

not always what they might seem. Have you ever wondered why grackles look iridescent blue in good light and black in bad light? Or why the colorful gorgets of male hummingbirds appear and then disappear without warning? This is because color in birds is not a simple thing. But rather it is a complex concoction of some very specific recipes. There are two main ingredients that are essential in the making of color. The first is pigment and the second is keratin. And the ways in which these two fundamental ingredients are added to the color cooking pot are what produces the final colors that we see. Pigments are relatively simple color makers. There are three main pigments that give feathers their colors. The first pigment is called melanin and it produces black or dark brown coloration. Melanin is also very strong and is thus often reserved for the flight feathers. White feathers are caused by a lack of pigmentation and are much weaker than black feathers due to the lack of melanin. This might explain why many predominantly-white bird species have entirely black or black-tipped feathers in their wings. These feathers are exposed to the greatest wear

"Pied kingfisher" by Вых Пыхманн - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

and are required to be stronger than regular feathers. The second group of pigments are called carotenoids and they produce red, orange or yellow feathers. Carotenoids are produced by plants. When birds ingest either plant matter or something that has eaten a plant, they also ingest the carotenoids that produce the colors in their feathers. The pink color of flamingoes, for example, is derived from carotenoids found in the

"Piranga olivacea1". Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

crustaceans and algae that the birds sieve from the water. The third group of pigments are called porphyrins and these are essentially modified amino acids. Porphyrins can produce red, brown, pink and green colors. This pigment group is the rarest of the three pigment groups and is found in only a handful of bird families. The best-known example of porphyrins is the red pigment (often called turacin) that is found in many turaco species and turacoverdin, the green pigment found in many of the same turaco

species. Mixtures of pigments can also produce different and unusual color hues and shades. For example, the dull olive-green colors of certain forest birds is actually a mixture of yellow carotenoid pigments and dark-brown melanin pigments. Then we get to the second main ingredient that produces color: keratin. Keratin is the tough protein of which feathers are made. It also covers birds’ bills, feet and legs. Keratin is responsible for the iridescent coloring of many spectacular bird species. How keratin produces color is a rather complex process but, from what I’ve read on the subject, I shall attempt to simplify it as follows. Keratin produces color in two main ways: by layering and by scattering. Layering colors are produced when translucent keratin reflects short wave-lengths of colors like blues, violets, purples and greens. The other colors are absorbed by an underlying melanin (black) layer. The ways in which the keratin of the feathers are layered will dictate the color of the iridescence. Examples of layered coloring include the iridescence of glossy starlings and the speculums or wing patches of many duck species. Scattering is produced when the keratin of feathers is interspersed with tiny air pockets within the structure of the feathers themselves.

"Merops ornatus - Centenary Lakes" by JJ Harrison (jjharrison89@facebook.com) - Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Commons.